After taking the public markets by storm in 2021, SPACs are facing a reckoning. We look at how this alternative to the traditional IPO works — and the opportunities and risks involved.

SPAC mania has grabbed the attention of investors, startups, and regulators alike.

A special purpose acquisition company (SPAC) is a “blank check” shell corporation designed to take a company public without going through the traditional initial public offering process. Instead, SPACs go public as shell companies, then later acquire and merge with target companies to bring them public on the stock market.

Though SPACs have been around for decades, the financial maneuver has gained traction in recent years — with high-profile names such as WeWork, Grab, and SoFi opting to debut via SPAC in 2021 — as more private companies eye exit opportunities and as the IPO market remains uncertain due to macroeconomic factors like the pandemic and geopolitical conflict.

DOWNLOAD THE FULL REPORT BELOW

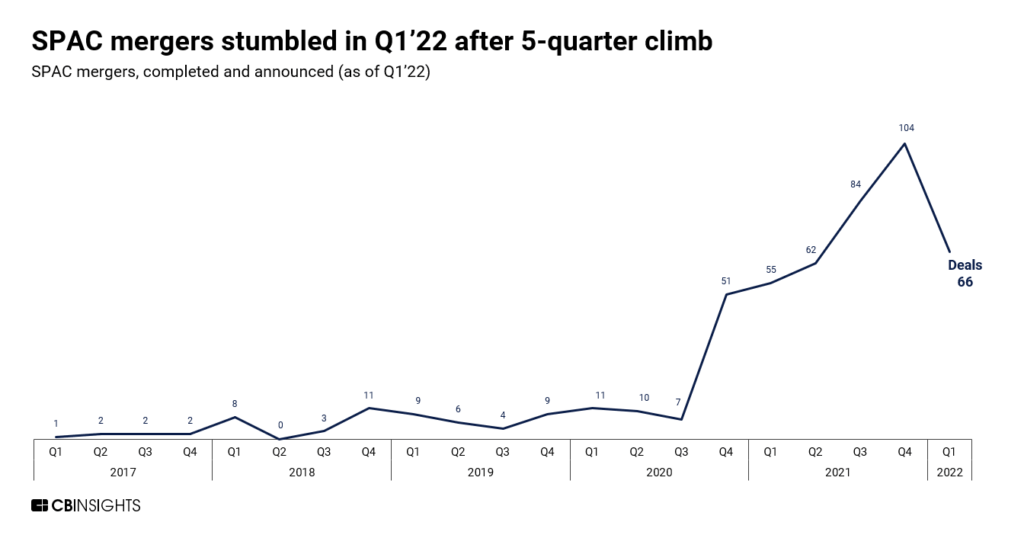

In fact, the number of SPAC mergers (including both announced and completed acquisitions of target companies) hit new records every quarter in 2021 to peak at 104 in Q4’21, although the pace has slowed in 2022 so far.

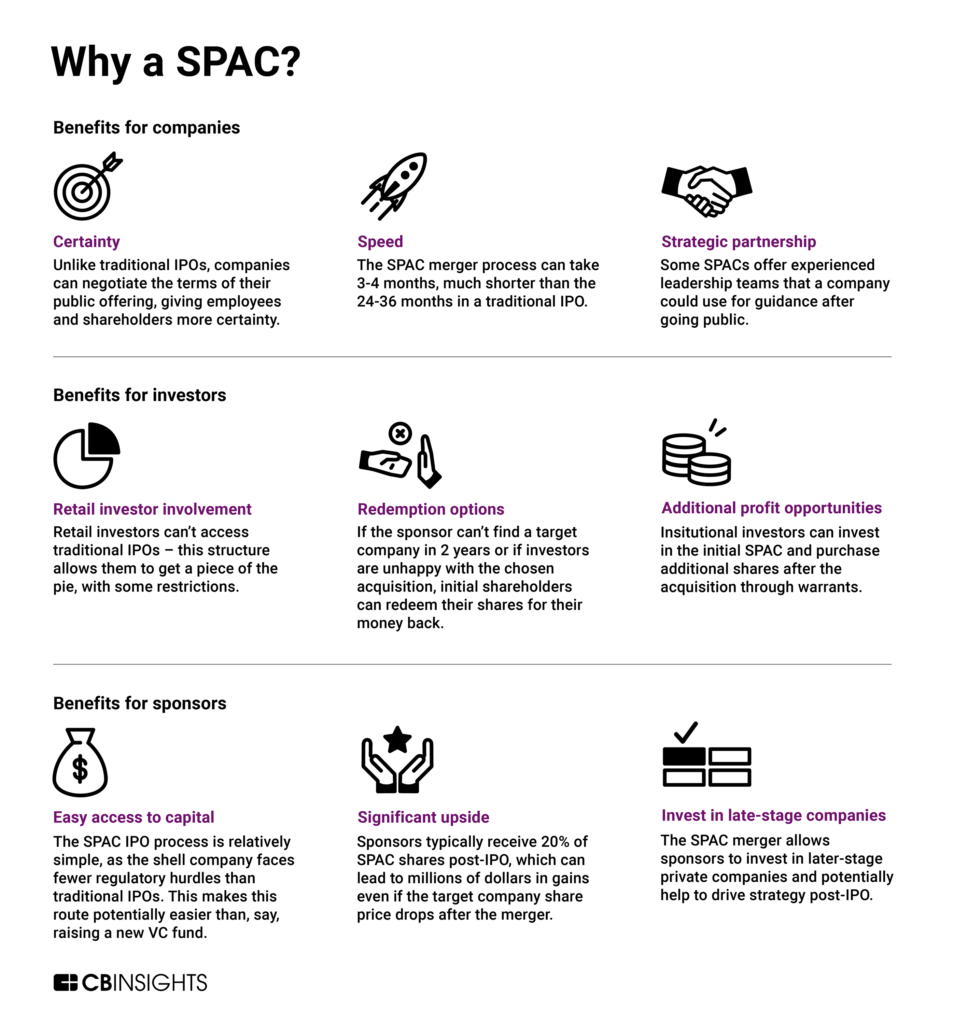

There are several reasons why investors and startups are turning to SPACs. The target company is able to go public quickly without much of the volatility associated with a traditional IPO, and investors get access to high-reward investments with limited risk.

Nearly anyone can start a SPAC, which is enticing a cross-section of big names including entrepreneur and VC Peter Thiel, former quarterback Colin Kaepernick, and baseball exec Billy Beane to get involved. Social Capital CEO and “SPAC King” Chamath Palihapitiya has launched a handful of SPACs since acquiring and debuting space company Virgin Galactic in 2019. He has reportedly reserved 26 public company tickers in total for SPAC public offerings — from IPOA to IPOZ.

But some have criticized the method as a “shortcut” to the traditional IPO, bypassing many of the necessarily strict regulatory requirements. In particular, a slew of electric vehicle startups have gone public via SPAC to much hype — though few have produced any vehicles for sale.

Additionally, once a SPAC is public and has identified a target company, it will generally use forward-looking statements about that company’s financial performance in its pitch to investors — a practice restricted for companies going public via a traditional IPO. Some SPAC mergers have received flack for appearing to mislead investors with exaggerated growth projections. In March 2022, the SEC proposed new rules that could bring this practice to a halt.

Despite the flood of SPACs, their market performance to date has lagged. The price of one exchange-traded fund (ETF) that tracks SPAC performance has sunk 37% in the last year (as of late March), while the S&P 500 has grown by nearly 18% during that time.

In this report, we examine how SPACs work, why they’ve grabbed the spotlight, and who the potential winners and losers are when it comes to this type of public market debut. We also look at what it means for the future of the IPO.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- What is a SPAC?

- Why are SPACs booming?

- Why are private companies going public via SPAC?

- Why are SPACs popular among investors?

- Challenges & concerns: SPAC risks

- Looking ahead: The future of the traditional IPO

What is a SPAC?

A special purpose acquisition company (SPAC) is a public shell company that acquires a private company and takes it public. Also called a “blank check” company, SPACs go public before their acquisition target is identified.

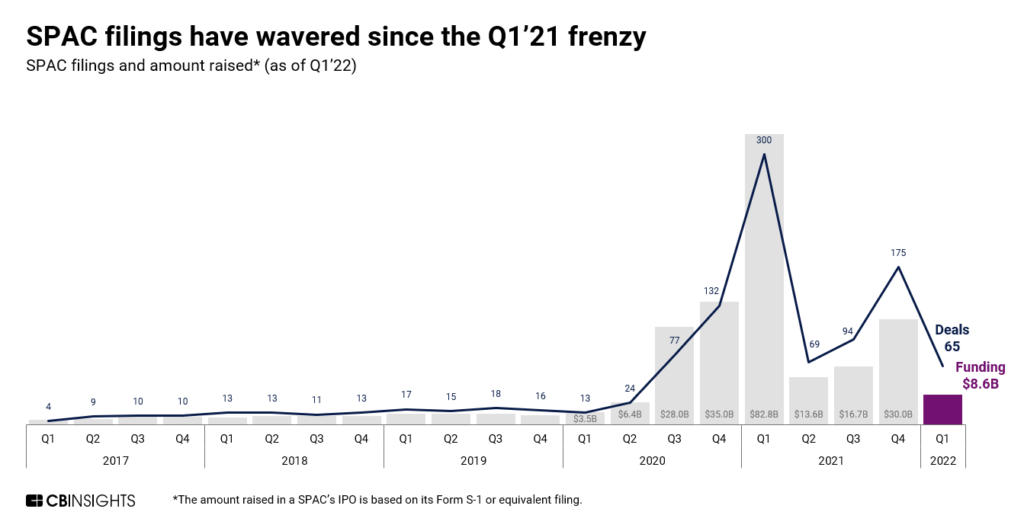

The SPAC IPO has been around in its current form since the 1990s, but the surge in popularity is more recent. 2021’s SPAC proceeds of $143B nearly doubled 2020’s record $73B.

In the 1990s, the SPAC had a reputation for taking small, immature companies public for a large fee, leading to high levels of company failure and lackluster stock performance at the expense of investors.

Regulations enacted in the 2000s helped to bring SPACs back into the spotlight, but the financial maneuver lost traction following some high-profile failures in 2008. Some credit Chamath Palihapitiya’s Virgin Galactic SPAC in 2019 as helping boost the exit type’s profile and set the stage for its popularity in the years following.

How do SPACs work?

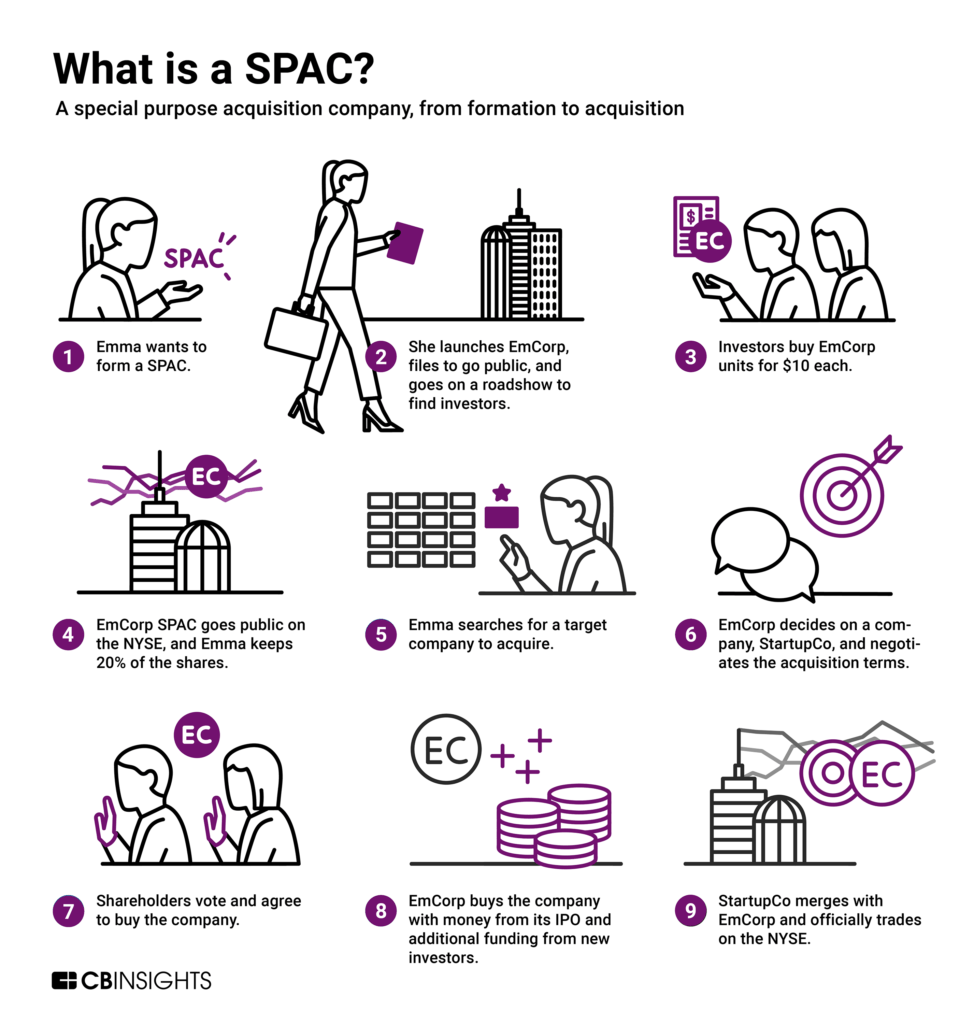

The following infographic walks through an example of a SPAC merger:

The SPAC process broadly takes place across 3 stages: the SPAC is formed and goes public; the SPAC identifies and acquires a target company; the SPAC merges with the acquired target and takes this company public (a process known as a “de-SPAC”). We dig into each of these below.

GOING PUBLIC USING A SPAC

The sponsor — typically a person or team with significant business experience — decides to launch a SPAC.

They create a holding company, then complete the normal filings associated with going public — but because the company doesn’t do anything (i.e., it has no operational business), the filing process is fast and easy.

The sponsor then goes on a roadshow, similar to traditional IPOs, to try to find interested investors. The difference here is that they are selling themselves, their team, and their experience, rather than a specific company.

Once the sponsor has attracted enough interest, they sell units in the company. Units are typically $10 each, and represent one share of the company and a warrant to buy more shares in the future. The money raised from the IPO is put into a blind trust and is untouchable until the shareholders approve the acquisition transaction or redeem their shares.

The SPAC goes public and trades on an exchange like any other publicly traded company. This is where retail investors get involved — they can purchase shares on the open market, but the future acquisition is still unknown. Instead, these investors are buying on the strength of the sponsor or the promise of a strong future acquisition.

The sponsor also receives 20% of the shares of the SPAC as a fee, called a “promote” or “founders shares.”

2021 saw a whopping 638 SPAC filings, garnering a combined $143B, far surpassing 2020’s 246 filings and $73B raised. Nearly half of these arrived during the first quarter of 2021, before an SEC statement in April 2021 — stipulating new accounting rules for SPACs — sent companies scrambling to double-check their financial statements for errors. New SPAC filings plummeted to just 69 in Q2’21 and have remained unsteady since then, as SPACs face increasing levels of scrutiny.

ACQUIRING A COMPANY

Once the SPAC is public, the sponsors can begin the hunt for a target company to acquire.

There are no restrictions on the type of company a SPAC can acquire, though many will highlight a target industry before IPO. Typically, the sponsors have 2 years to find and announce an acquisition, or else the SPAC will dissolve and shareholders will get their money back.

When the sponsors find a company, they then negotiate the terms of the acquisition with the target company, like purchase price or company valuation.

Following a deal, the “de-SPAC” process begins.

DE-SPAC

After deciding on the terms of the acquisition, the sponsors must propose the acquisition target to shareholders.

Importantly, unlike an IPO, the de-SPAC acquisition is not considered a public offering — and is therefore protected by safe harbor laws that allow forward-looking statements in filings. It can be appealing for sponsors and target companies to be able to forecast future growth in their investor presentations, especially if the target has little (or no) revenue under its belt — although painting a rosy picture has the potential to mislead investors. As of March 2022, the SEC is finalizing rules that would limit this behavior by applying the same investor protections to SPACs that traditional IPOs have.

The initial shareholders have the opportunity to vote on the acquisition, which gives them some recourse if a sponsor chooses a company they do not like. Even if the acquisition is approved, shareholders can then redeem their shares for their money back.

Once the company is approved and all redemptions have been completed, the sponsor can move forward with acquiring the target company.

However, the initial SPAC raise usually only covers about 25-35% of the purchase price. Here, the sponsors can ask existing institutional investors (like large funds or private equity firms) or new outside investors for additional money using a Private Investment in Public Equity (PIPE) transaction.

Following the final capital raise, the SPAC can now take the target company public.

Even though the SPAC is already public and has filed with and been approved by the SEC, the target company also needs to gain approval from regulators. In other words, the target company does not necessarily face fewer regulatory requirements when going public via a SPAC merger instead of a traditional IPO — it’s just a shorter timeline.

Once approved, the ticker changes to reflect the name of the acquired company and it starts trading as a typical public company. For example, Social Capital’s IPOA SPAC acquired Virgin Galactic in 2019. On the day of the acquisition, the ticker IPOA stopped trading and was replaced with SPCE.

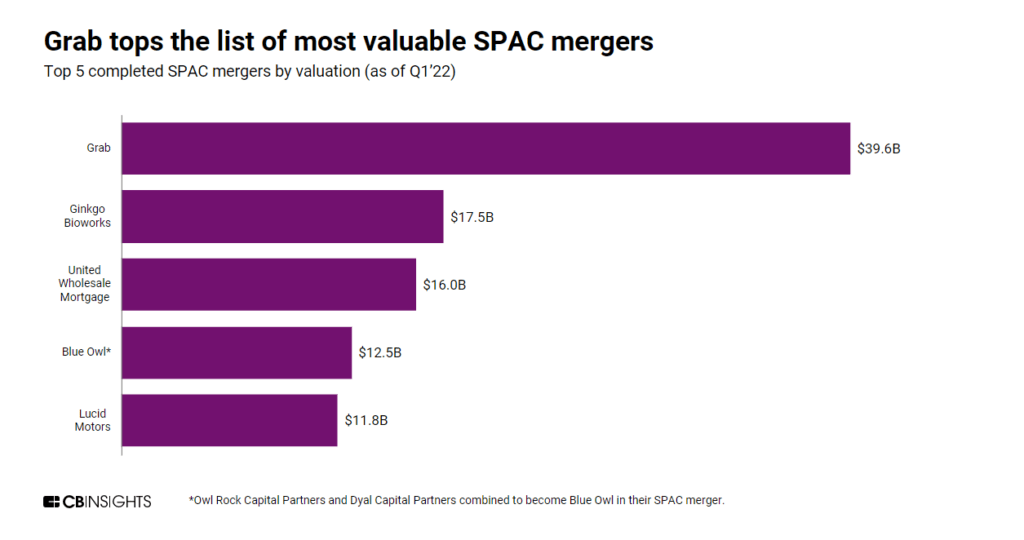

The largest completed SPAC merger to date is Grab’s $39.6B debut, followed by Ginkgo Bioworks ($17.5B), United Wholesale Mortgage ($16B), Blue Owl ($12.5B), and Lucid Motors ($11.8B).

Why are SPACs booming?

There are a few reasons why SPACs have recently experienced a boom in popularity.

For one, private companies have been staying private for longer. Many VC-backed companies have had ample access to capital, as investors with deep pockets like SoftBank and Tiger Global Management dole out $100M+ rounds, deferring IPOs while creating a larger supply of late-stage private companies.

SPACs have emerged as a more streamlined path to the public markets when the conditions to debut are in a mature company’s favor. Some of the 1,000+ global unicorns, under pressure from investors for an exit, could look to the SPAC as a quick way out.

The Covid-19 pandemic has also injected uncertainty into the market.

Throughout the pandemic, private companies have been less sure they’ll be able to raise large rounds in the near future, but still need access to capital. Some have looked to public markets for liquidity.

However, given the volatility of public markets, the traditional IPO might be less enticing, as companies have less control over how much money they are able to raise. The traditional IPO also takes years to complete, and the pressure to go public is pushing some companies to explore faster alternatives.

Sponsors and investors are therefore taking this opportunity to provide companies with that alternative — for a significant fee.

Why are private companies going public via SPAC?

There are a few reasons why private companies would choose to go public via SPAC instead of a traditional IPO.

In January 2021, healthcare D2C company Hims & Hers went public via a SPAC sponsored by Oaktree Capital Management at a $1.6B valuation. In the decision to go public, the company considered both a typical IPO and a SPAC. When discussing the process with Axios, Hims & Hers CEO Andrew Dudum said,

“We had always expected and prepped for a traditional IPO, but there are a lot of favorable dynamics in the new group of SPACs. There’s greater speed and certainty of a deal, which helps the team stay focused, and we get to partner with an amazing investor like Howard Marks [co-chairman of Oaktree].”

Some companies prefer the SPAC process to the traditional IPO process because of stability, speed, and strategic partnerships, despite the increased costs associated with sponsor fees.

Stability

In a typical IPO, the company’s share price is not certain. It is determined by investor appetite and market forces as much as by the company’s underlying business valuation. A company is unsure of how much it will make until the day before its IPO, even though it takes months to go through the IPO process.

Further, the traditional IPO price is determined by the IPO bankers, who make their best guess at what the company is worth in the eyes of investors. However, this is never perfect, meaning that the IPO can be mispriced. If a company’s bankers priced its IPO at $10/share, but then it immediately pops to $15, this means that the company may have been able to sell its shares at a higher price, missing out on more money.

A SPAC transaction is appealing because it avoids price uncertainty altogether. The company’s management team is able to negotiate an exact purchase price, ensuring that the company doesn’t leave any money on the table, though it pays a price for this certainty — the valuation received may be lower than a company could receive through a traditional IPO, and the sponsor fees add additional costs.

However, the market has been shaken by a recent trend: SPACs are seeing increasingly high rates of share redemption, in which institutional investors pull money out of deals before the merger is complete (more on how redemptions work below). In the first 2 months of 2022, the average redemption rate for a SPAC merger reached 80% — meaning 4 out of 5 shares were redeemed before the target was acquired — up from about 50% in 2021 and just 20% in 2020.

This can put a huge dent in the amount of capital a company can raise in the offering. Added to high sponsor and transaction fees, some companies have dropped their SPAC deals altogether. Kin Insurance, for instance, bailed on its SPAC plans, citing high redemption rates, and instead raised an $82M Series D in March 2022. Micro-investing app Acorns did the same, raising $300M in March 2022 after pulling the plug on its $2.2B SPAC.

Speed

The traditional IPO can take years from start to finish.

The SPAC merger process is much faster for the target company, taking as little as 3 to 4 months, according to PwC. This is attractive for companies looking to raise money and go public quickly.

However, the time crunch does mean the company has to prepare to be a public company much quicker, despite needing to complete all the same filing requirements as a traditional IPO. This includes financial reporting, SEC oversight, tax preparation, technology upgrades, cybersecurity measures, and more.

Strategic partnership

Though not every SPAC plans on being a strategic partner to the company it takes public, the strategic SPAC has become a typical pitch for some of the tech companies that are looking to go public fast.

Strategic SPACs use sponsor experience and knowledge as a selling point for potential companies. For example, an electric vehicle company may find a SPAC offering more appealing if the sponsor comprises a team of EV investors or operators, especially if the sponsor plans to take a board seat and work with the company’s management team on post-IPO strategy.

In this way, the strategic SPAC serves a similar purpose as venture capital does to private investment: the company benefits not only from the investment itself, but also from the investor.

Why are SPACs popular among investors?

This has proven to be an enticing strategy for many investors, including institutional and retail investors, as well as the sponsors behind the SPAC.

SPAC sponsors

SPACs are very attractive opportunities for sponsors, who stand to make significant amounts of money in most cases.

One challenge for sponsors is to convince people and funds to invest hundreds of millions, and at times billions, of dollars in their SPAC. For this reason, many SPAC sponsors are well-known in their field or have a team of experienced businesspeople.

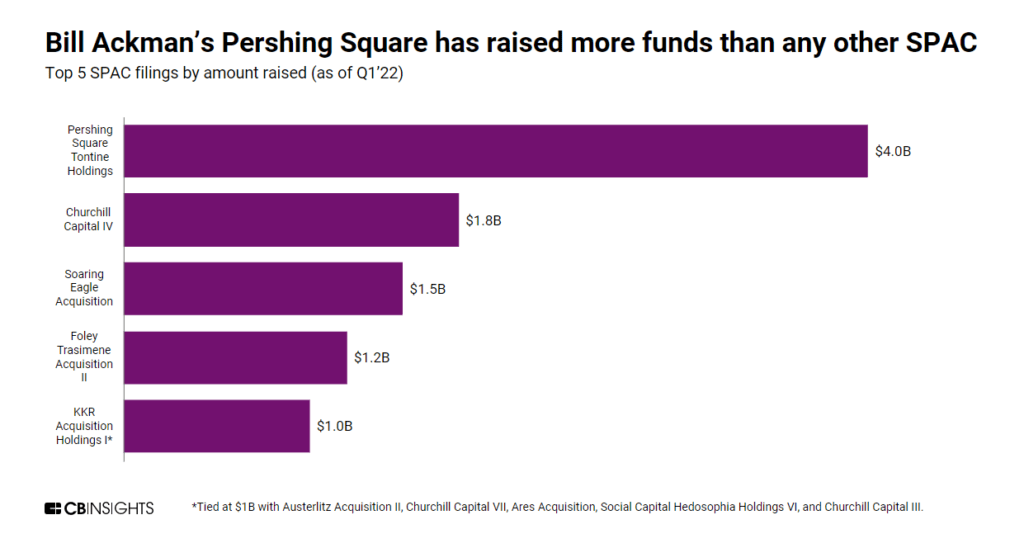

Hedge fund manager Bill Ackman raised $4B for a SPAC in July 2020 — the most raised for a SPAC to date. However, Ackman has opposed the current SPAC structure, which gives sponsors huge upside opportunities and severely limits their downside.

As it currently stands, SPAC sponsors pay about $25,000 to receive 20% of the SPAC shares, assuming a deal is completed. For example, if a SPAC raised $500M initially, the sponsor pays $25K and gets $100M in shares once the merger occurs. This is a huge profit margin and is not severely impacted if the acquired company performs poorly — even if the new company’s stock drops by 50%, the sponsor still makes nearly $50M.

To try to remove these incentives, Ackman forfeited the 20% founders shares. He also claimed that his hedge fund, Pershing Capital, would invest $1B+ of its own capital to complete the merger. The IPO was very successful, with about 3x more interest in the offering than was available.

However, the activist investor’s SPAC has had a turbulent path: it originally announced it would acquire 10% of Universal Music Group for $4B in an unusually engineered deal, but it soon dropped that plan after SEC scrutiny. Ackman has since looked to convert the SPAC into what he calls a SPARC (special purpose acquisition rights company), which allows investors to wait to pledge capital until an acquisition target has been selected.

Nevertheless, sponsor-friendly rules are still the norm, so the SPAC process remains incredibly attractive for well-known individuals and firms as a way to make significant amounts of money with relatively little risk.

Institutional investors

Institutional investors, like pensions, hedge funds, mutual funds, or investment advisors, have long invested in SPACs and other less traditional funding vehicles. In fact, the top 75 investment managers reportedly held almost 70% of all SPAC securities as of late 2020.

This structure is attractive for these investors mainly because of the limited risk they face when investing: when investors get in before the IPO, they receive warrants, which allows them to buy more shares after the target company is announced for only slightly more than the initial purchase price. They are also able to redeem their shares if they are unhappy with the acquisition decision, and get their money back if a company isn’t purchased within 2 years.

This makes SPACs nearly risk-free for hedge funds, and they’ve been reaping the profits: hedge funds that redeemed their shares saw an average annualized return of 11.6% on their initial investment, according to a study conducted by Michael Klausner of Stanford Law School and Michael Ohlrogge of New York University School of Law.

For example, if a hedge fund buys 1,000 shares in a SPAC at $10 each, it also receives 1,000 warrants to buy more shares for $11.50 a piece. When the target company is announced, the fund can redeem its shares for all of its money back, limiting its potential losses if it thinks the company will not do well. However, if the target company goes public and its stock jumps to $15, the hedge fund still has warrants to buy 1,000 more shares for $11.50 each — making a potential profit.

Retail investors

Retail investors — individuals making investments through traditional or online brokerages like Robinhood — are not allowed to invest in a traditional IPO, and therefore have to buy on the open market on the day of trading. This means that retail investors are largely left out of the upside available from an IPO.

These investors have a unique, albeit mixed, opportunity with SPACs. The structure allows retail investors to get involved in a SPAC after it has gone public but before it has announced the merger, which allows them to enjoy the “pop” once the business to acquire is announced.

However, these investors are favoring the sponsor, not the company to go public, which adds risk. While institutional investors and retail investors have the same rights to acquire and redeem SPAC shares, retail investors often buy common shares on the open market at prices higher than $10 (thereby missing the first-day pop) instead of units (which includes shares and warrants). For example, brokers like Robinhood don’t offer warrants, while other brokerages like TD Ameritrade or Vanguard have hefty fees to split units. Institutional investors, however, are usually able to ink more favorable deals, acquiring units at $10 a pop.

Furthermore, retail investors that buy and hold are likely to lose money — the average share price for completed SPACs in 2020-2021 clocked in at just $8.70, a 13% decline from the average $10 starting price, despite the stock market as a whole finishing 2021 strong.

On the flipside, nearly every single participating hedge fund sells or redeems its shares before a deal is completed, which may also affect SPAC prices later on. The warrants that are doled out to early investors also bring about the risk of share dilution.

In other words, if institutional investors get a lot of the reward with limited risk, retail investors get a lot of risk with limited upside.

Challenges & concerns: SPAC risks

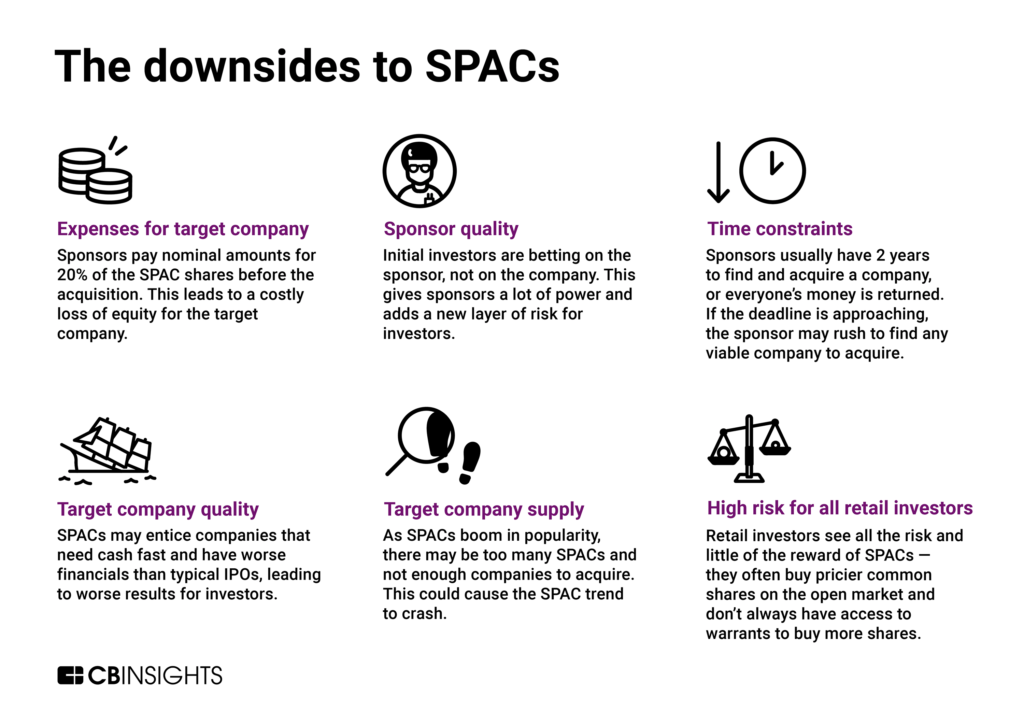

Despite the positives, there are also challenges and concerns regarding the structure of the SPAC method.

From sponsor risk to low-quality companies to supply & demand concerns, SPACs are far from perfect.

Sponsors’ perverse incentives

For decades, the SPAC has had a negative reputation as a way for sponsors to get rich quickly at the expense of other investors.

For instance, from January 2019 to January 2021, SPAC sponsors saw an estimated 958% average return on their investment.

Though SEC regulations and improved sponsor quality have helped to boost the SPAC reputation, there are still risks and downsides associated with the sponsor, including:

- Expenses for the target company. Sponsors pay nominal amounts for a 20% ownership of the SPAC shares, which can lead to a 1-5% stake in the acquired company after the business merger. This means that sponsors are poised to make significant income if they merge — regardless of the outcome of the merger — which may disincentivize appropriate due diligence on target companies. It also costs the target company a large portion of equity, which could make this deal more expensive than a traditional IPO.

- Sponsor quality. Investors in the initial IPO are investing in the sponsors, not in a specific company — giving sponsors a lot of power while adding a new layer of risk for investors. Institutional investors are able to redeem their shares and get their money back at the time of the acquisition announcement, but there is little a retail investor can do if it’s proven after the merger that the sponsor didn’t do proper due diligence or chose in bad faith.

- Time constraints. The sponsor typically has 24 months to find and acquire a company, or else the SPAC is liquidated and everyone’s money is returned. If that deadline is approaching, the sponsor may rush to acquire any willing company, potentially harming investors.

However, as the quality of sponsors has improved over the years, it has helped add some credibility to the structure and push the SPAC into the spotlight.

Quality of target companies

For a struggling company, a SPAC may provide a temporary lifeline that’s faster to access than an IPO.

One study showed that, between 2003 and 2013, 58% of companies that merged with SPACs failed — a higher rate than traditional IPOs.

Even if companies don’t fail outright, some negative press may have an outsize impact on the SPAC reputation for companies considering this process in the future.

For example, electric truck company Nikola went public via SPAC in March 2020, despite not earning any revenue in 2019 and lacking a clearly viable truck model. It saw its market cap jump to $29B — higher than Ford‘s — before its CEO and chairman resigned and the SEC opened an investigation into the company for fraud.

Nikola is not alone. In a Wall Street Journal analysis of the performance of 2021’s SPAC acquisition targets that had less than $10M in annual revenue — suggesting minimal commercial traction — nearly half missed their 2021 revenue projections. The average miss was by 53%, a significant margin.

Stories like these tend to taint the reputation of SPACs, pushing other companies away from the structure. This contributed to a precipitous drop in the number of completed SPACs in Q1’22.

Supply of target companies

Another concern is that the number of SPACs may outpace the number of companies willing to go public. Legally, the sponsor is not allowed to express interest or discuss a merger with any potential target companies, which means that, while sponsors may have potential companies in mind, they take their SPACs public without knowing the demand for a future SPAC merger.

The 2-year time limit for acquisition also plays into this concern. If demand for companies to acquire is greater than the companies ready or willing to go public, the SPAC bubble could burst as sponsors lower their quality standards for target companies or as the SPAC expires. And with over 600 SPACs currently looking for targets, it’s likely more than a few of these will walk away empty-handed.

“Is there too much SPAC money chasing too few opportunities? … I don’t think we know that yet.” — Jeff Sagansky, media executive and SPAC sponsor

High risk for retail investors

Retail investors get all of the risk — and limited rewards — associated with SPACs.

Retail investors that buy and hold on open markets frequently lose out, because they’re typically buying in at a premium. Those that hold onto their shares for a stake in the merged company are overwhelmingly losing money: SPACs recorded a median post-merger return of negative 65% in the 12 months after a merger, according to a 2021 study from Klausner, Ohlrogge, and Emily Raun. Overall, high redemption rates and share dilutions make investing in SPACs potentially risky for investors that aren’t as familiar with SPAC incentives and structures.

Looking ahead: The future of the traditional IPO

The future of the IPO is not in jeopardy.

Many high-profile companies that are looking to go public in the coming years are rejecting the SPAC option, opting instead to go public the traditional way. For example, Airbnb was reportedly approached by Bill Ackman’s $4B SPAC, but the company ultimately decided against this route, instead debuting via traditional IPO in December 2020.

It is still more expensive to go public via SPAC, and outside of periods of market volatility, there may be less incentive to pay that higher price to avoid the uncertainty of a traditional IPO.

The SEC also has no love lost for the once-archaic financial instrument. Its April 2021 crackdown led to a precipitous drop in SPAC filings — highlighting the fragility of a once-exploding market — and it has investigated several SPACs for wrongdoing, including charging a space transportation SPAC in July 2021 for misleading investors. John Coates, then-acting director of the SEC’s Division of Corporation Finance, said of the charges,

“Concerns include risks from fees, conflicts, and sponsor compensation, from celebrity sponsorship and the potential for retail participation drawn by baseless hype, and the sheer amount of capital pouring into the SPACs, each of which is designed to hunt for a private target to take public. With the unprecedented surge has come unprecedented scrutiny, and new issues with both standard and innovative SPAC structures keep surfacing.”

In March 2022, the SEC also put forth plans to regulate SPACs more strictly, along the same lines as traditional IPOs. In a statement of dissent, SEC commissioner Hester Peirce said the rule proposal “seems designed to stop SPACs in their tracks.”

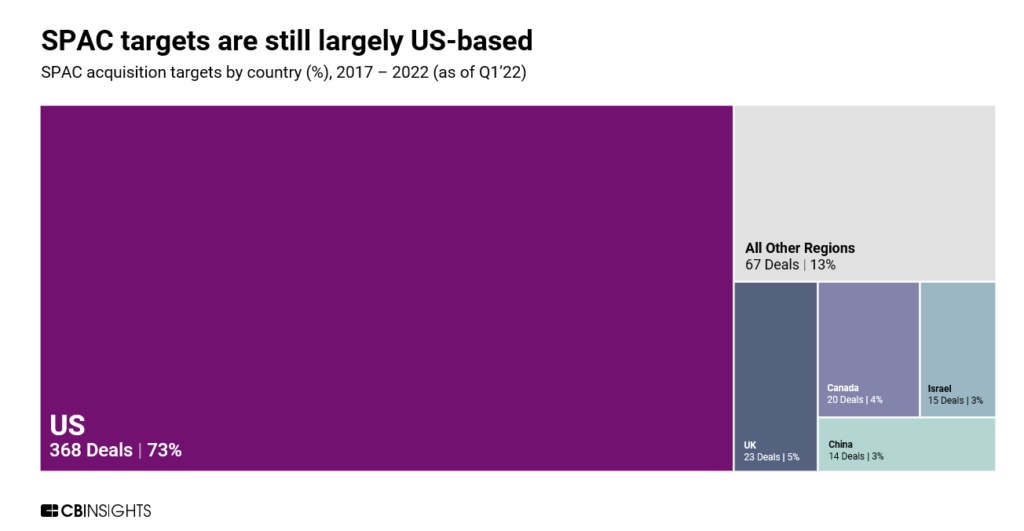

The SPAC boom has also yet to pick up in popularity beyond the US, with 3 out of 4 SPAC acquisition targets based in the US. A notable exception is Southeast Asia-based ride-hailing and food delivery giant Grab, which closed a $39.6B SPAC merger — the largest ever — in late 2021.

The appetite for foreign companies to go public via SPACs is comparatively small vs. the US. In Asia, few stock exchanges allow for SPACs, although regulatory bodies in tech hubs like Singapore are starting to warm up to them. Meanwhile, Europe-based SPACs are still largely unproven and face a stricter regulatory environment. For instance, it is more difficult in Europe for an investor to redeem warrants if they dislike the proposed acquisition target.

Litigation and regulatory risks present another major obstacle in the future of SPACs. Between September 2020 and March 2021, at least 35 SPACs were slapped with lawsuits in New York for reasons like inadequate financial disclosures, per law firm Akin Gump, while CFO Dive reports that 17% of SPAC deals between 2019 and 2020 faced litigation. Securities class action suits involving SPACs grew 6x YoY in 2021.

Ultimately, the SPAC merger is likely here to stay, though probably not in its current form.

Today, sponsors are the big winners of the SPAC boom. However, if the supply of SPACs outpaces the number of companies ready to go public, sponsors will have more competition for deals, which could force sponsors to be more company-friendly — such as by offering less dilutive terms — to entice potential acquisition targets.

This could strengthen SPACs’ reputation, in effect creating a virtuous cycle where each successful SPAC drives more investor interest and startup demand for future ones.

If you aren’t already a client, sign up for a free trial to learn more about our platform.