What are challenger banks? Who’s who? And why have they raised billions in venture capital to take on bank incumbents? We break down how these companies are reaching, converting, and engaging millions of customers.

Challenger banks have gained traction over the past decade by developing streamlined, digital-first retail banking services.

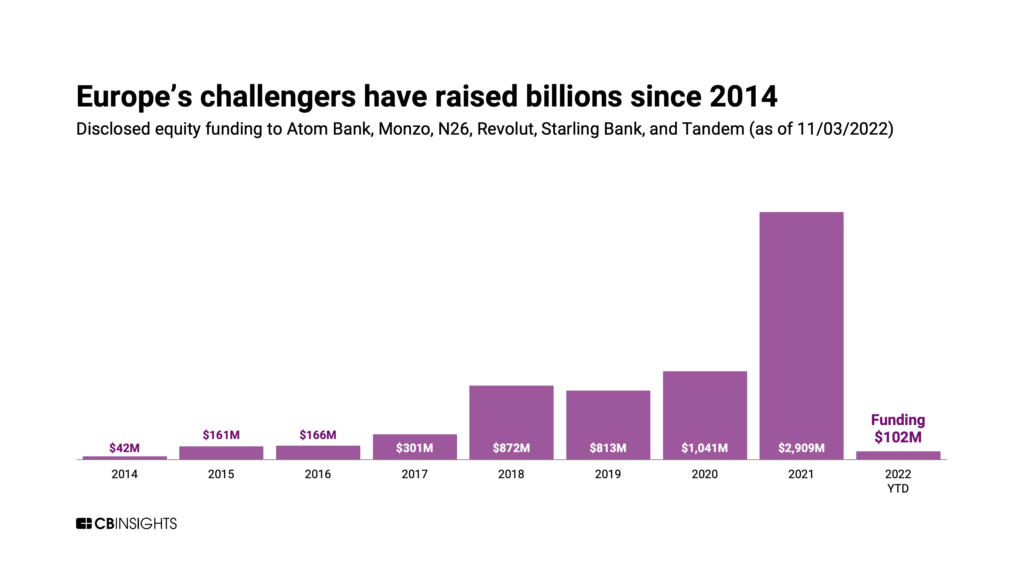

Europe saw the first cohort of challenger banks break out. Since 2014, Europe-based challengers Atom Bank, Tandem, Monzo, Starling Bank, Revolut, and N26 have collectively attracted $6B+ in funding and over 37M customers.

The UK, in particular, was an early incubator for challenger bank activity compared to other regions, as a result of progressive regulations enacted to promote competition and break up monopolies. However, more recently, challenger banks have appeared in other regions around the world, from Australia to Asia to the US.

In this report, we explain what challenger banks are, dive into the playbooks of notable challenger banks, assess how different regulatory approaches have impacted growth, explore paths to profitability, and highlight future trends to watch.

Table of Contents

What is a challenger bank?

- Challenger banks vs. traditional banks

- The shift from in-person to digital banking

How challenger banks leveraged regulation to launch and grow

- 3 regulatory strategies for launching challenger banks

- New regulations help challenger banks expand services

- Challenger banks in the Australian market

The path to profitability for challenger banks

- With network effects, banks can earn massive profits from fees

- Revenue diversification lets smaller or niche banks thrive

Looking ahead: Trends to watch

- Focus on profitability & responsibility

- An increasingly crowded market

- New products & partnerships

- New markets for challenger banks

What is a challenger bank?

Challenger banks are tech companies that leverage software to digitize and streamline retail banking. Challengers use digital distribution channels, typically mobile, to offer competitive retail banking services such as checking and savings accounts, loans, insurance, and credit cards.

Challenger banks vs. traditional banks

Unlike traditional retail banks, which offer physical branches for in-person banking, challenger banks take a digital-first approach, often relying solely on mobile and desktop platforms. Challengers prioritize an improved user experience, appealing to those who want to be able to bank from their phones instead of visiting a retail location.

Challenger banks first made inroads with consumers who lost faith in institutional firms following the 2008 global financial crisis. These companies “challenge” the traditional incumbent business model by charging customers transparent, low fees, providing faster services, and delivering a better user experience through always-available digital interfaces.

Further, many challenger banks target demographics that may be underserved by traditional banks, like consumers in lower income brackets or those lacking credit history.

The shift from in-person to digital banking

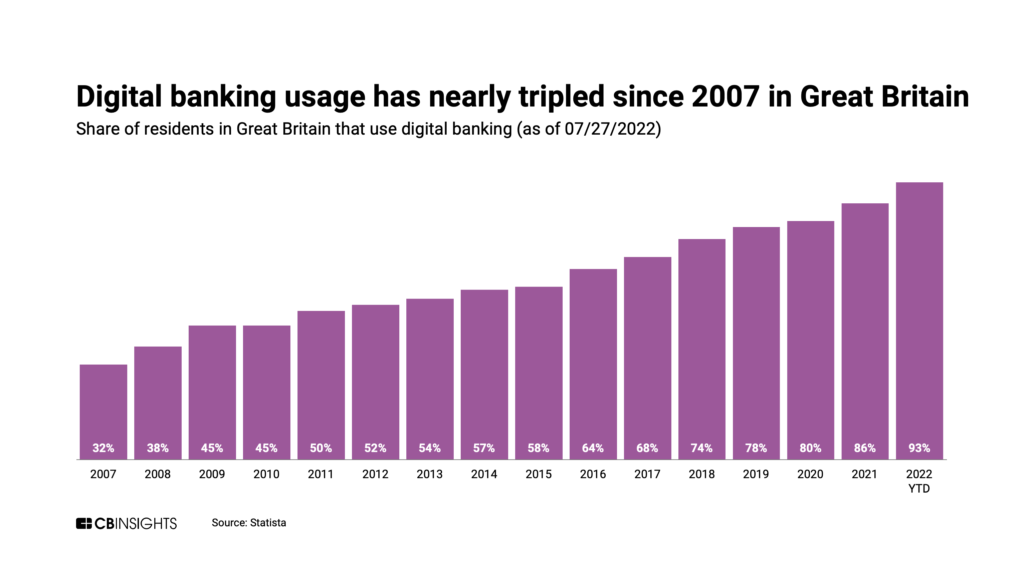

In 2009, there were 240K bank branches across Europe. At the time, customers still relied heavily on bank branches and were just starting to embrace online banking. But challenger banks bet that online — particularly, mobile — would be the next channel for retail banking distribution. That has proven prescient.

Since then, the rise of digital banking has mirrored declines in branch banking. The number of bank branches in the European Union has been slashed to 143K. And it’s expected that another 20,000 will close by 2023, according to consulting firm Kearney.

Juniper Research predicts that, by 2026, 4.2B people will be using digital banking services, which include both mobile and desktop channels. Among specific markets, Britain has seen some of the most widespread adoption of digital banking services.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, global shutdowns and branch closures further accelerated digital banking adoption — a boon for many challengers. For example, global mobile banking and payment app usage grew 26% in the first half of 2020 compared to the same period in 2019, according to an Adjust and Apptopia survey.

Challenger banks have benefited greatly from the transition to digital, as incumbents still maintain a branch-centric business model. Nevertheless, traditional banks have also developed their own digital offerings, investing significantly in digital transformation to keep up with shifting consumer demand.

How challenger banks leveraged regulation to launch and grow

In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, the EU’s progressive regulators have made it easier for challenger banks to obtain the financial licenses necessary to operate. We’ll examine how 6 challenger banks (Atom Bank, Tandem, Monzo, Starling Bank, Revolut, and N26) took advantage of the new regulatory environment to grow.

Atom Bank, Tandem, Monzo, and Starling Bank — all based in the UK — and Germany-based N26 all obtained a full bank charter, which takes up to 2 years to process but widens the services these banks can offer consumers. In pursuing this time-intensive process, these challengers were betting that a charter would build trust with consumers and allow them greater flexibility in building their offerings.

UK-based Revolut’s strategy, on the other hand, was to get an e-money license, which can be obtained much more quickly, though the scope of services that can be offered is more limited. This option was created in 2011, as part of the UK’s Electronic Money Regulations.

Challenger banks have also been able to expand within the EU by leveraging the European Economic Area (EEA) passport. The passport enables a firm licensed in 1 of the 27 EU member states to provide financial products or services in another country without needing further authorization. N26, for instance, has used the passport to expand its service to over 20 EEA countries.

Below, we delve into the divergent regulatory strategies these companies used to acquire customers and launch their first products.

3 regulatory strategies for launching challenger banks

TRADITIONAL APPROACH

Atom Bank, Tandem, and Starling Bank prioritized having a bank charter prior to launch and built a suite of services that required a charter, believing it would create a moat around the platform. Atom Bank, for example, launched a savings account and a lending product for small- and medium-sized businesses (SMBs) after regulatory approval.

The biggest drawback to this approach is missing the first wave of early adopters. Because of the time-consuming regulatory approval process, Atom Bank was behind on getting a product to market and didn’t launch until mid-2016, 18 months after registering with the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA).

Another drawback to the charter is that it can be revoked. Tandem lost its banking charter after failing to secure funding. It acquired Harrods’ bank division in late 2017 as a way to restore its charter, but that was a costly and time-intensive process.

SEMI-TRADITIONAL APPROACH

Monzo and N26 wanted to get customers onto the platform while they sought charters.

Monzo did this by launching a prepaid card instead of a full account product. The benefits of this strategy include getting products to market faster, getting customer feedback, and fixing bugs during early product releases. But a drawback is that it can jeopardize growth.

Monzo was going through a period of rapid growth, adding a reported 60K users a month, when the company was granted a charter. In December 2017, it stopped adding new customers and announced plans to transition its 500K existing customers off of prepaid cards and onto Monzo’s own current accounts. While it worked to complete this task and reopen registration, Monzo lost out on the activity of hundreds of thousands of waitlisted customers.

Another drawback of this approach is that players must rely on corporate partners while waiting on a bank charter. In N26’s case, it used payments processor Wirecard‘s back-end to get its payments interface up and running. This meant giving Wirecard a cut from every transaction.

FAST-LANE APPROACH

Revolut challenged the conventional go-to-market strategy by applying for an easier-to-acquire e-money license and targeting currency exchange rather than current accounts (similar in use to checking accounts in the US). Revolut initially focused on frequent travelers, a niche it believed was underserved. It built a digital currency exchange app, which allowed people to exchange money more frequently across countries without needing to establish multiple bank accounts.

Revolut leveraged the EEA passport to expand across Europe and partnered with other fintechs to iterate quickly. It was able to launch this product without waiting on a charter, while gaining access to a roster of potential clients for an eventual banking offering.

Revolut has continued to add new products that boost its customer acquisition efforts. For instance, soon after announcing a cryptocurrency trading feature in its app in late 2017, the company crossed the 1M user mark, adding 3.5K users per day.

In 2018, it became the first challenger bank to announce that it was breaking even on a monthly basis. This means that the company was monetizing enough customers to offset the cost of acquiring new ones.

Revolut has since received an EEA charter through the Bank of Lithuania and applied for a charter in the UK in the first quarter of 2021. The company now counts 20M+ individual customers and 500K+ business customers.

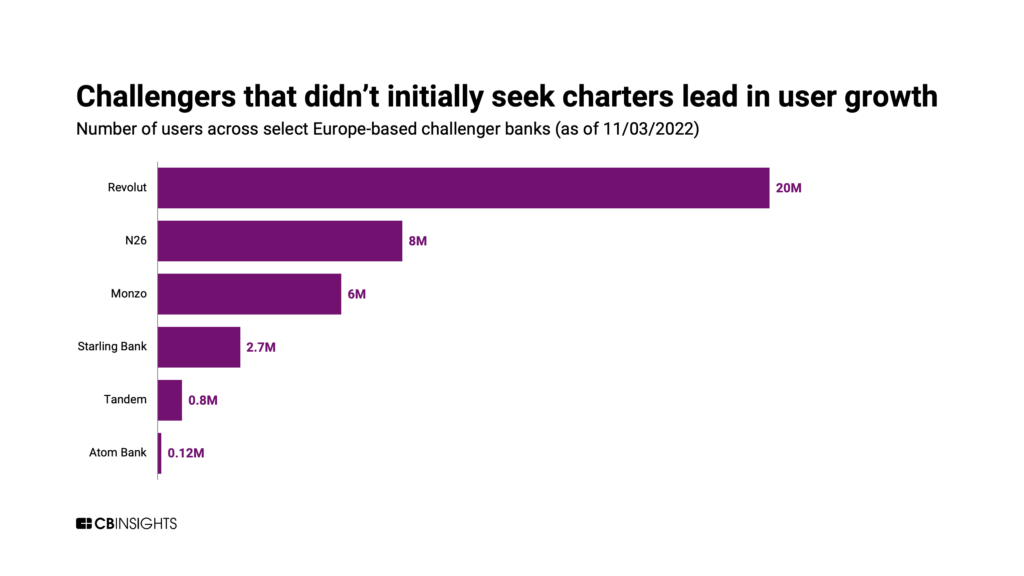

The fastest-growing challenger banks — Revolut, Monzo, and N26 — acquired customers rapidly through viral growth strategies and without first seeking a bank charter. As of November 2022, the 3 banks have a combined customer base of over 34M users.

The other 3 companies — Tandem, Starling, and Atom — waited to launch products until receiving their charters, which took up to 2 years. Because of this, these banks burned more cash along the way than their non-chartered counterparts. To date, they have a combined 3.6M customers, just around one-tenth of what their competitors have collectively amassed.

New regulations help challenger banks expand services

In recent years, regulators in the EU and UK have continued to actively enable challenger banks’ growth. This includes regulations like the UK’s open banking standards and the EU’s Revised Payments Services Directive (PSD2), which both went live with phased rollouts in January 2018.

The open banking standards require the UK’s 9 largest bank providers of personal and business current accounts (including Lloyds, Barclays, HSBC, and Santander) to implement open standards for application programming interfaces (APIs).

Open banking and PSD2 standards allow third parties to safely and securely access customers’ account data at their request. This means there’s a big opportunity for fintech companies like challenger banks to plug into traditional banks and build new services for consumers.

Challenger banks in the Australian market

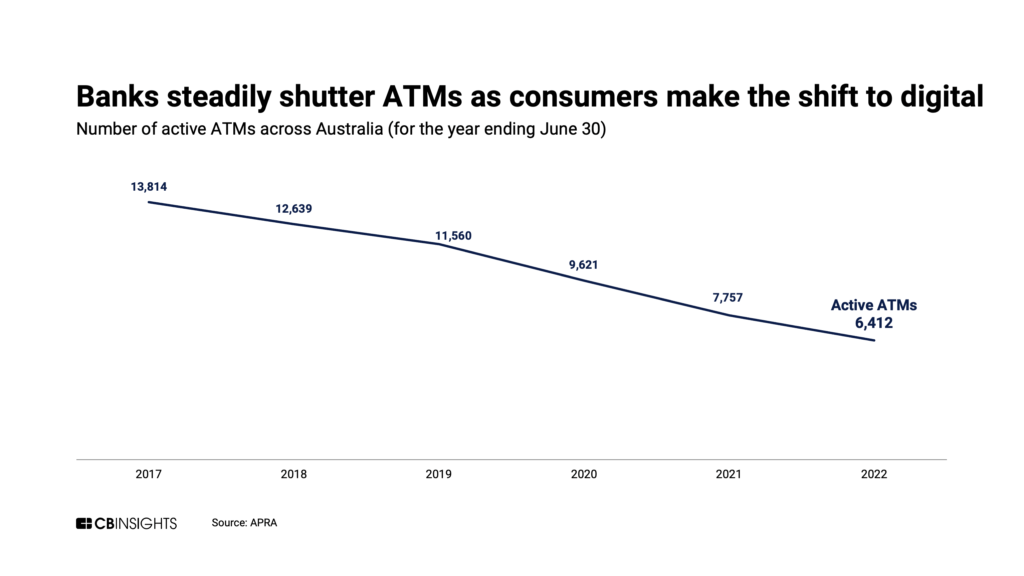

While challenger banks in the UK and Europe have established themselves as known names over the past decade, the Australian banking sector opened to this kind of disruption in 2018. The ups and downs of the nascent Australian challenger bank market serve as a case study — and cautionary tale — for challengers in other regions.

Australia began to welcome challengers after a spate of regulatory changes went into effect in May 2018. These regulatory changes were the result of a year-long investigation into alleged misconduct by many Australian banks.

The Australian banking sector is dominated by 4 big banks: Commonwealth Bank of Australia, Westpac, National Australia Bank, and ANZ Banking Group. Together, they account for 74% of the Australian banking sector, according to data from IBISWorld.

To minimize fraudulent behavior among Australian banks, a Royal Commission made 76 recommendations. Among these was the creation of a license for restricted authorized deposit-taking institutions (ADIs), issued by the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA), which would allow challenger banks to operate in a restricted fashion for 2 years while working toward a full ADI license.

Five notable challenger banks emerged out of this regulatory shift: Up, Judo, Volt, Xinja, and 86 400.

Up, one of the first challenger banks to come to the Australian market, did not go the route of acquiring a license. Instead, the bank launched in October 2018 in partnership with Adelaide Bank and Bendigo Bank, which allowed it to circumvent the requirement to get a license and establish a trusted reputation early on.

Judo received its full banking license in April 2019 and was founded with the goal of helping small businesses get loans and lines of credit, among other things. The challenger bank attained unicorn status in December 2020, after a $212M Series D round, which valued it at $1.2B. It went public via IPO in November 2021.

With a strong lending portfolio, Judo is one of the most robust challenger banks in the Australian market. Judo claims that business picked up during the Covid-19 pandemic, as it added nearly $800M of lending to its portfolio, citing customers’ delays and difficulty in accessing traditional banking services during the onset of the crisis. Data from APRA underscores Judo’s claim. During the early stages of the pandemic, the challenger bank’s loan portfolio increased by 40% to nearly $2B, even as overall lending to small businesses fell by 2%.

Volt was the first Australia-based challenger bank to receive a restricted ADI license in May 2018 and then the full license in January 2019. However, it did not immediately launch a banking product. The bank started out by setting up Volt Labs to create awareness about its brand and build trust with its customers to make the transition from a big legacy bank to a challenger bank easier. Volt also partnered with Microsoft and cloud-based tech provider Lab3 to provide white-labeled banking services to other fintech companies in Australia.

However, the Covid-19 pandemic created uncertainty for a number of challenger banks in Australia. Volt was forced to delay its plans to IPO in 2020, and it ultimately closed its business altogether and returned its license in July 2022. It cited the impact of “the pandemic and the current challenging global economic climate” as contributing to its inability to secure the funding necessary to keep the business going.

Another Australia-based challenger bank hurt by Covid-19-related uncertainties was Xinja. The bank, which had taken the ADI route in 2019, was forced to relinquish its banking license and return A$500M ($378M USD) in customer deposits in December 2020. Xinja chalked it up to “COVID-19 and an increasingly difficult capital-raising environment affecting who is willing to invest in a new bank.” Its customers were transitioned to National Australia Bank.

Xinja had entered the market with a prepaid card linked to a mobile app that tracked spending and offered advice on optimizing expenses. It then launched a savings account that offered a high interest rate of 2.25%. This service may have led to the bank going under, as Xinja was unable to generate the cash required to deliver on the promise of high-interest payouts. The bank never created a lending product, from which incoming interest could have offset the interest it was paying to its customers.

Another challenger to emerge was 86 400, a consumer payments and lending platform that was granted a banking license in July 2019. Soon after, the bank announced a $21M funding round led by Morgan Stanley. However, 86 400’s stint as an independent banking entity was short-lived — it was acquired by National Australia Bank (NAB) in January 2021 and merged with UBank, NAB’s own digital bank.

The path to profitability for challenger banks

Fewer than 5% of challenger banks are profitable, according to Simon Kucher & Partners. The majority aren’t even close to breaking even.

There are 2 primary models for achieving profitability:

- Some challenger banks aim to reach a scale where revenue from interchange fees will make them successful.

- Others, especially those that serve niche audiences, focus on product and revenue diversification.

These 2 profit models are not mutually exclusive. Brazil’s Nubank — the world’s largest challenger bank with 70M users across Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico — applies both models. It focuses on increasing the value of each of its customers by cross-selling a variety of products — a digital account, credit cards, insurance, loans, investments, and payments (for businesses).

Nubank posted a profit in Brazil for the first time in H1’21 and saw record quarterly revenue of $887M in Q2’22. While Nubank went public in December 2021 at a $41.5B valuation, its market cap has since fallen by 44% (as of November 2022) amid volatile economic conditions.

With network effects, banks can earn massive profits from fees

Interchange fees are transaction fees that a business’ bank pays to its customer’s bank whenever that customer makes a payment using a credit or debit card. Many challenger banks in the US rely heavily on debit interchange fees, which typically amount to 1.2% of the transaction value.

Interchange fees can become a significant revenue driver for a challenger bank only if that bank reaches a sufficiently large number of customers. But 2 obstacles make it difficult to achieve this network effect.

First, many account holders still have their primary accounts in legacy banks. This trend is shifting among younger demographics, though. In the US, for instance, 28% of Gen Z and 31% of millennials have a primary checking account at a digital bank, and that percentage is growing, according to Cornerstone Advisors. Coupled with this trend, 25% of Gen Z and 23% of millennials have a primary account at a mega bank, and that percentage is decreasing.

One challenger bank that has succeeded in gaining scale and capitalizing on network effects is US-based Chime. Of its 13M+ customers, 8M use it as their primary bank. Chime became profitable — though only in terms of EBITDA — during the pandemic.

Another trend that makes it risky to rely too much on interchange fees is the growing popularity of account-to-account transactions, thanks to the increased adoption of digital wallets and social commerce. These transactions are associated with reduced interchange fees for businesses and, according to PYMNTS, rose by 60% in 2020. Millennials and Gen Z, in particular, are opting to use mobile wallets more often than debit or credit cards, even when paying at brick-and-mortar stores.

Revenue diversification lets smaller or niche banks thrive

Diversification is crucial for the vast majority of challenger banks that have not achieved enough scale to profit from transaction fees. In Europe, where interchange fees have been capped at 0.2% and 0.3% for debit and credit card transactions, respectively, challenger banks offer loans as a way to increase revenue and target both consumer and business clients.

A banking license is a critical advantage for diversification, as it authorizes the institution to provide a wider range of financial products and services. Three UK challenger banks that offer loans and have approved charters have reported attaining profitability:

- Starling Bank reported its first full-year profit in July 2022

- Redwood Bank, which secured a UK banking license in 2017, made its first profit in late 2021

- Zopa became profitable for the first time in April 2022, just 21 months after obtaining a UK banking license

In contrast, Revolut, which holds an e-money license in the UK but has a European banking license, saw its revenue surge in 2020 thanks to fees from crypto and stock trading. It broke even by November of that year. Revolut also offers insurance products and paid monthly memberships to unlock a range of financial services.

Looking ahead: Trends to watch

In 2022, challenger banks are focused on proving their ability to make a profit, complying with new regulations, and diversifying their products amid competition on all sides — coming from fintech disruptors, tech giants, and traditional corporations.

Focus on profitability & responsibility

TIGHTER MONETARY ENVIRONMENT AND LOOmiNG RECESSION FORCE CHALLENGERS TO CONSERVE CASH

Capital is tight in 2022. Driven by volatile markets and widespread uncertainty, global venture funding dropped by 34% QoQ in Q3’22 — the largest quarterly percentage drop in a decade.

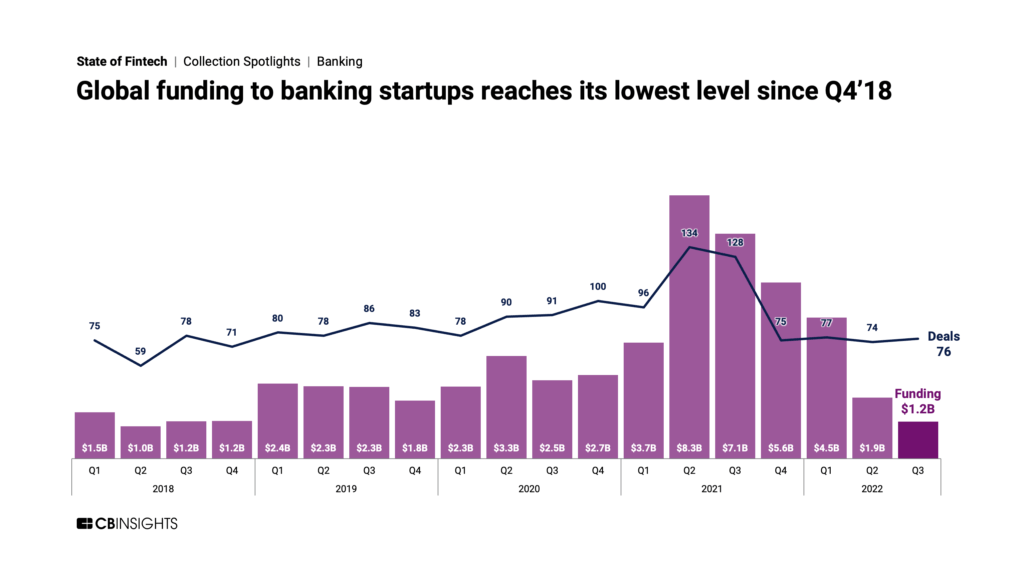

Fintech startups, in particular, may be losing their former luster: They accounted for just 17% of all tech funding in Q3’22, down from a recent high of 25% in Q2’21. More specifically, banking-focused fintechs raised a total of $1.2B in Q3’22, marking an 83% drop YoY.

Rising inflation rates are threatening some challenger banks’ business models. To survive, some may need to raise prices on the services they provide, which could undercut one of the main ways they differentiate from legacy banks. For instance, raising loan rates (to combat the effects of inflation) could alienate a bank’s customers if cheap loans were central to its value proposition.

Challenger banks that offer above-market interest rates on savings accounts may also suffer if they don’t have enough capital to pay out returns, especially if they haven’t sufficiently deployed deposits as loans to earn income.

Without the option of raising more venture capital, some challengers will need to focus on near-term profits and tighten their spending. The worst-case scenario for these challengers is that they collapse. Australia’s Volt, for example, folded in June 2022 after failing to raise additional funding. Earlier this year, due to its high burn rate, it looked like Varo, a challenger bank with a US charter, could run out of money by the end of 2022 without an influx of funds. Since then, it has taken steps to reduce its burn rate and attempt to put itself back on the path to profitability.

Few challenger banks have a cash cushion large enough to allow them to keep focusing on growth mode without seeking out more capital. A rare case is Revolut — earlier this year it said it would not be raising money within the next 2 years. However, since then, its revenue has plunged amid the broader crypto downturn.

REGULATORS SEEK TO REIN IN FRAUD

Challenger banks are coming under greater regulatory scrutiny, particularly relating to financial fraud and crime.

For instance, in April 2022, the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) published a review of financial crime and anti-money laundering (AML) controls at 6 unnamed challenger banks, which collectively had 8M customers. The review was prompted by the release of the UK’s 2020 national risk assessment of money laundering and terrorist financing, which highlighted the risks associated with challenger banks’ speedy onboarding processes.

The FCA found that:

- Several challenger banks had weak financial crime controls, poor management of transaction monitoring alerts, underdeveloped consumer risk assessment frameworks, and vaguely detailed due diligence processes

- Challenger banks’ fast onboarding processes were linked with insufficient Know Your Customer (KYC) practices in some cases, leading some to fail to identify high-risk clients

- Some challenger banks didn’t allocate sufficient resources to monitoring financial crime

Summing up its findings, the FCA stated, “there cannot be a trade-off between quick and easy account opening and robust financial crime controls.”

To balance speed of service and compliance, challenger banks need to double down on regtech (regulation technology), which uses AI and automation to perform KYC checks and AML monitoring at scale.

Some challengers are already making moves here: For instance, UK-based Recognise Bank, a challenger bank for small businesses, announced in July that it had partnered with regtech TruNarrative to make its onboarding process both faster and more compliant.

An increasingly crowded market

NON-TRADITIONAL COMPETITORS EMERGE FROM BIG TECH AND CORPORATIONS

Tech giants like PayPal and Apple are not banks, but they can leverage their massive consumer bases and product ecosystems to siphon consumer activity away from both traditional and challenger banks.

PayPal wants to become a super app where consumers can shop and use a number of consumer financial services. It already offers a Mastercard-based debit card and features for bill payments, direct deposit, buy now, pay later (BNPL), and more. Similarly, Apple offers a Mastercard-based credit card and BNPL options, in addition to popular challenger bank features like transaction categorization.

In Asia, tech giants are also moving further into banking. Grab, a Southeast Asia-based super app that started out as a ride-hailing app, launched GXS Bank in Singapore in partnership with Singtel, a telco. It has full banking licenses in Singapore and Malaysia, and its first product was a savings account.

Non-financial corporations are also entering the banking space.

Walmart, for instance, partnered with investor Ribbit Capital to launch a fintech startup in 2021. Since then, the startup has acquired 2 other fintechs (ONE and Even), and the combined company — called ONE — now offers a single app where consumers can save, shop, and borrow. At the time of the acquisitions, Walmart planned to integrate the app into its own operation in order to provide financial services to consumers — both directly and via employers and merchants.

LEGACY BANKS TRY TO DISRUPT THE DISRUPTORS

Legacy banks have tried (and sometimes failed) to create their own digital banks. In 2019, JPMorgan Chase closed down Finn, its digital bank, which had amassed only 47K customers in a year of operation. Bó by NatWest had an even shorter life, closing down 6 months post-launch after gaining just 11K customers.

JPMorgan Chase’s second act is faring better. It launched a digital retail bank in the UK in September 2021, and by May 2022, the arm had gained 500K customers with a combined $10B in deposits and had processed around 20M card and payment transactions. By September, it hit 1M customers and 92M transactions.

Goldman Sachs is putting up a fight even as its Marcus digital bank faces a loss of $1.2B in 2022. GS views Marcus as being a crucial channel for opening up new revenue streams and aims to see $4B in revenue from it in 2024. Marcus currently has 14M+ customers and more than $100B in deposits. It also offers BNPL for home improvement through GreenSky, which it acquired in September 2021 for $2.2B.

Traditional banks might also look to acquire a challenger bank instead. The consolidation process, however, can be rocky. In the year following National Australia Bank’s takeover of Australian challenger bank 86 400, roughly 35% of the employees who remained with the merged entity left. Some former staff cited the culture clash between the challenger and the legacy bank as their reason for leaving.

New products & partnerships

CHALLENGER BANKS DIVERSIFYING THROUGH FINTECH PARTNERSHIPS

For challengers like Revolut and N26, partnering with other fintech companies to add new services has helped them drive down costs and move forward on the path to profitability.

Following this, other challenger banks may ramp up partnerships, especially in the wake of the UK’s open banking standards and the EU’s PSD2. For example, Starling Bank quickly took advantage of the standards, launching a BaaS API marketplace in 2018 and seeking integrations with numerous fintech startups.

Moneybox was one of Starling Bank’s earliest partnerships. Moneybox is a digital wealth management startup that makes fractional investments for customers with spare change that is topped off of every purchase. Moneybox leveraged Starling’s API to improve the investment allocation time from once per week to real-time.

One drawback to this approach, however, is that it’s easy to replicate. For instance, Moneybox has also partnered with Monzo and had an existing partnership with Revolut. Other challenger banks will also likely increase partnerships to achieve cheaper customer acquisition, increase speed to market with new services, and contain upfront infrastructure costs.

Challenger banks may also look to partner with the bulge bracket banks they set out to disrupt in order to take advantage of new open banking requirements, accelerate network speed, and ensure information security. For instance, smaller challengers like Tandem and Atom Bank may look to benefit from larger institutional partnerships as they launch new product categories like alternative credit cards and alternative mortgages.

Because partnerships are costly and create contingency risk, some challenger banks will look to bring products in house through acquisitions. Tandem, for example, acquired Allium, a lender that helps consumers bring green energy into their homes, in August 2020. The bank also snapped up Oplo in January 2022 to expand its consumer lending portfolio to include mortgages, home improvement loans, auto loans, and more.

Brazil’s Nubank is leveraging partnerships to break into a new fintech vertical altogether: cryptocurrencies. In May 2022, it partnered with blockchain infrastructure firm Paxos to allow its customers to trade bitcoin and ether through its mobile app. After just 1 month in operation, the crypto offering had gained 1M users.

The challenger doubled down on this strategy when it announced, in October 2022, that it would launch its own cryptocurrency in 2023. The token, called Nucoin, will be built on Polygon’s blockchain network. Nubank’s goal with the cryptocurrency is to increase customer engagement by offering discounts and perks across its financial products to token-holders.

CHALLENGER BANKS START OFFERING BUY NOW, PAY LATER SERVICES

Challenger banks are implementing buy now, pay later (BNPL) features to provide more flexible payment options to their customers, while also tapping into new revenue streams. BNPL is estimated to reach $1T in global annual gross merchandise by 2025, representing a massive opportunity for banks and fintechs.

Monzo and Curve launched BNPL products in September 2021, and more challenger banks are following suit. These include Zopa (UK), Revolut (in Ireland, Poland, and Romania), and Plazo (Spain).

Monzo’s BNPL product, Monzo Flex, for example, lets customers spread the cost of purchases over 3 installments without interest, while payments spread over 6 or 12 installments incur a 24% annual percentage rate (representative, variable).

Meanwhile, Zopa announced that it would roll out its BNPL offering in a staggered manner in order to align with the development of UK government BNPL regulation. Earlier this year, the UK government announced that BNPL providers will be required to conduct affordability checks, ensure clear and fair advertising, and gain approval from the Financial Conduct Authority. Revolut, which is positioning its service as “responsible BNPL,” says it would conduct soft credit checks using open banking data to qualify customers.

While challengers have to compete with established BNPL players like Klarna, they can potentially offer customers more flexibility in shopping. When using Klarna and other pure-play BNPL providers, consumers are typically limited to the provider’s merchant partners. In contrast, a shopper can use their challenger bank account to pay at a wide range of online and physical stores.

Challengers aren’t alone in identifying the opportunity. Legacy banks have quickly launched their own BNPL products and could be at an advantage, given their massive user bases.

DIFFERENTIATING PRODUCTS THROUGH DEMOGRAPHIC TARGETING

Some challenger banks are focusing on products aimed at highly specific communities and socioeconomic demographics to differentiate themselves in an increasingly crowded market.

In the US, for instance, companies like Kinly, Greenwood, and Cheese focus on underserved minority communities like new immigrants and Black Americans, while Daylight focuses on the LGBTQ+ community. Letter and Unifimoney are building private banking products for high-net-worth individuals, while Capway is focusing on the underbanked by offering low thresholds for account holders. Capway does not require a monthly minimum balance or charge overdraft fees, and it allows users to access their direct deposit early. Along these lines, TomoCredit launched a credit card in March 2021 that does not rely on credit scores — instead, it uses cash-flow data to ascertain a consumer’s creditworthiness. With this product, TomoCredit is targeting young people who may not have credit history.

The same diversification is taking place in Brazil, which has proved a fertile ground for challengers. There, Lady Bank is serving the needs of women in business, Pride Bank caters to the LGBTQ+ community, and Zippi provides credit to micro-entrepreneurs and the self-employed.

This increasingly granular market approach introduces an added layer of competition and puts pressure on challengers to uniquely define their value propositions. Shruti Rai, co-founder of UK-based challenger bank Novus, recommends that new challengers focus on a theme and build services around it in order to engage their customers’ interests.

Novus positions itself as an “ethical challenger bank.” When customers use the Novus debit card to pay for purchases, they earn “impact coins” that they can donate to a cause. The Novus app also has a marketplace featuring sustainable and ethical brands, and customers earn cashback rewards when they shop from those brands.

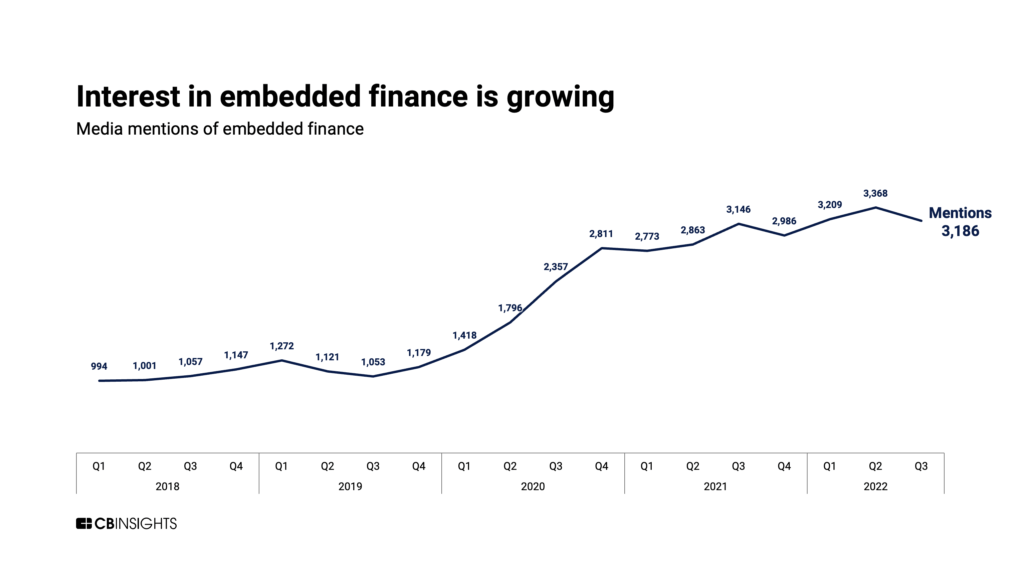

FINDING NEW OPPORTUNITIES IN EMBEDDED FINANCE

Embedded finance — the practice of non-financial companies offering dedicated financial services, like lending, to customers — is also on the rise. Players in a wide range of sectors are increasingly building banking onto their existing services as an invisible layer. Examples include:

- Gaming: Mana Interactive, a gaming app, launched banking services in May 2022 using embedded finance solutions provided by Helix by Q2, a cloud-native core designed for embedded finance. Mana now offers a checking account and a Visa-powered debit card for gamers that comes with gaming-related rewards and discounts.

- E-commerce: Shopify encourages its merchants to “skip the bank” by opening a Shopify Balance account. Shopify Balance is backed by Evolve Bank & Trust through Stripe’s embedded banking platform.

- Employee solutions: Lyft offers its drivers a debit card and bank account powered by Canada-based PayFare, a digital banking app. Both Lyft’s and Shopify’s embedded banking services are aimed at enabling drivers/merchants to get paid faster and save better.

- Retail: Retail pharmacy chain Walgreens offers Scarlet — a bank account and debit card. Customers earn cashback rewards when they use Scarlet to shop at Walgreens. Walgreens uses InComm Payments’ BaaS platform.

- Corporate services: H&R Block, a tax services company, launched Spruce — a fintech that partners with banks to provide spending and savings accounts, a debit card, advance paychecks, and a feature for saving part of one’s tax refund. Spruce is powered by Pathward, a South Dakota-based national bank formerly known as MetaBank.

For non-financial companies to provide select financial services to their customers, they need fintech infrastructure, which is time-consuming and expensive to build. Because challenger banks already have this infrastructure and the expertise to roll out these services, they stand to gain by contributing to embedded financial services through providing banking-as-a-service.

While fintechs without banking licenses can offer BaaS through their tech stacks and e-money licenses, licensed challenger banks have an edge. They don’t need to partner with a bank to offer products like loans and savings accounts to their BaaS clients, which means they can keep more of the revenue. They can offer not only their technology but also a full suite of financial products and services.

Starling Bank, which started offering BaaS in the UK in 2018, announced the global launch of its services earlier this year. It targets companies across digital banking as well as non-financial sectors like healthcare, retail, and utilities. Aside from extending its banking tech and products, Starling also provides automated AML and KYC solutions to help clients comply with financial regulations.

CHALLENGER BANKS SNAP UP FINTECHS

As fintech valuations have plummeted in 2022, challenger banks with enough cash on reserve may look to acquire startups at a discount to expand their technology, product suite, or market reach.

For example, earlier this year, Nubank was reportedly looking for fintechs to acquire at a price cut. Starling Bank was also said to be building “a war chest for acquisitions” with a budget of £400M ($470M USD), following a fresh influx of funds from its existing investors.

A number of challengers have already made moves on this front. Examples include:

- In March 2022, Danish challenger bank Lunar announced plans to buy Norway-based Instabank for $135M. Instabank operates in Finland, Germany, Sweden, and Norway and offers savings accounts as well as secured and unsecured loans. Lunar raised $77M at a valuation of $2B that same month.

- Chetwood Financial acquired Yobota for an undisclosed sum in March 2022. Yobota will provide the core banking system to BaaS clients, while Chetwood’s banking license will enable the merged entity to offer a wider suite of financial products and services.

- After securing $37M in Series C funding in March 2022, farmer-focused challenger bank Oxbury bought its platform provider Naqoda. Naqoda is being rebranded as Oxbury Earth and will be the bank’s platform for offering BaaS beyond the UK.

New markets for challenger banks

In addition to launching new products, challenger banks are betting on new markets beyond their home regions.

CHALLENGER BANKS IN THE US: A FRACTURED REGULATORY ENVIRONMENT

In their bids to enter the US market, N26, Monzo, and Revolut face significantly higher barriers to entry due to regulation and competition.

Not only must banks abide by federal regulations, but they also must adhere to the laws governing financial services activity in each state.

Challenger banks that do try to expand in the US also face competition from existing fintechs. In July 2020, US-based challenger bank Varo became the first fintech to receive a full bank charter in the US, although it took over 3 years to achieve and cost Varo an estimated $100M. Similarly, after years of effort, point-of-sale payments company Block (then known as Square) landed its own full-service banking charter in March 2021.

US fintechs that want to obtain a charter in less time may choose to acquire a traditional bank. In January 2022, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) and the Federal Reserve conditionally granted national bank status to SoFi after it bought Golden Pacific Bank, a community bank in California.

Seeking a full-service charter in the US is expensive, legally risky, and time-intensive, so going this route won’t be feasible for most challenger banks, domestic or abroad.

Even so, Revolut applied for a bank charter in the US in March 2021. While Revolut launched in the US with basic services in 2020 by partnering with a domestic bank, the charter would allow it to expand its products to include personal loans, deposit accounts, and business banking. With Revolut’s charter application in the UK still pending, though, its chances of getting approved in the US remain slim.

N26 and Monzo never got charter approval and chose different market entry routes instead. N26 launched in the US in 2019 through a partnership with Axos Bank but left in early 2022 to focus on the European market. Monzo finally entered the US in February 2022, just months after it withdrew its application for a banking license in the country. It has partnered with Ohio-based Sutton Bank to offer bank accounts to US clients, and it also offers a Mastercard debit card.

CHALLENGER BANKS IN LATIN AMERICA: A CHALLENGER BANK HAVEN

Latin America also represents a strong growth opportunity — and, subsequently, a competitive market — for challenger banks.

Seventy percent of the population in the region is unbanked or underbanked. In addition, mobile phone adoption is high in the region, at more than 70%. These 2 factors offer ripe conditions for challenger banks to disrupt the traditional banking sector.

N26 received its license to operate in Brazil in early 2021, after announcing plans to launch in the country 2 years earlier. Revolut is preparing to launch in Brazil by the end of 2022 and has applied for a license to operate as a direct lending business in the country.

Brazil, in particular, has become a vibrant market for challenger banks.

Alongside Nubank, another leading challenger bank in Brazil is Neon. Neon was founded in 2016 and has a focus on savings and investment products for Brazil’s working class and lower-income residents.

Argentina is South America’s second-largest challenger bank market after Brazil, with many players vying for customers. Uala is one of the largest. Founded in 2017, the challenger bank has expanded to Mexico and Colombia and now has 5M clients across Latin America. After acquiring Wilobank, a digital bank with a license, Uala is now expanding its services to include banking functions like payment of salaries and pensions.

Mexico is also fast becoming a challenger bank hub. An estimated 90% of the country’s residents don’t have access to credit cards, making it an ideal market for challenger banks. In addition, consumers are tech-savvy and willing to adopt digital banking solutions. Regulators are also embracing fintech companies to help boost financial inclusion. Within just 18 months of launching there, Nubank had onboarded more than 2M customers and become the country’s most active issuer of new cards.

CHALLENGER BANKS IN FRONTIER & EMERGING MARKETS

Frontier and emerging markets can be lucrative for fintechs that fulfill needs unmet by traditional institutions, provided that regulators in these countries welcome innovation. For unbanked individuals, a challenger bank has a good chance of becoming their primary bank — especially if that bank keeps barriers to entry low, such as by not requiring minimum account balances.

The Asia-Pacific (APAC) region is also home to a number of challenger banks. The region’s unbanked population of 1B people, coupled with strong mobile use, makes it an ideal market for digital finance solutions. According to Mordor Intelligence, 63% of banking customers in APAC could be using challenger banks’ services by 2025.

Within Southeast Asia, regulators in Malaysia, Singapore, the Philippines, and Vietnam have already granted full digital banking licenses. Banking in the region is fragmented owing to different regulations and languages, and no regional leader has emerged.

A similar narrative plays out in Africa, where over 400M people remain unbanked. One player aiming to form a pan-African bank is Kuda Bank. It started in Nigeria, where it has a microfinance banking license and claims to have around 5M users.

As challenger banks expand their reach, it’s evident that no product or market is off the table. However, they’ll need to make the right strategic bets in order to leverage regulation to their benefit and stand out from the rest of the pack.

If you aren’t already a client, sign up for a free trial to learn more about our platform.