Today, a new generation of disruptive brands are shaking up retail — direct-to-consumer e-commerce companies that build, market, sell, and ship their products themselves, without middlemen.

An explosion of new direct-to-consumer companies is transforming how people shop. In the process, these brands, spanning everything from detergent to sneakers, are radically changing consumer preferences and expectations.

The 22 companies we’ll look at were born on platforms that have marked the post-dot-com internet — Amazon, Facebook, Google, Instagram, and Kickstarter.

Direct-to-consumer brands have used that infrastructure to grow fast and connect directly to their customers.

get our direct-to-consumer cheat sheet

Learn secrets to success from our analysis of Casper, Glossier, Warby Parker, and 11 other D2C companies.

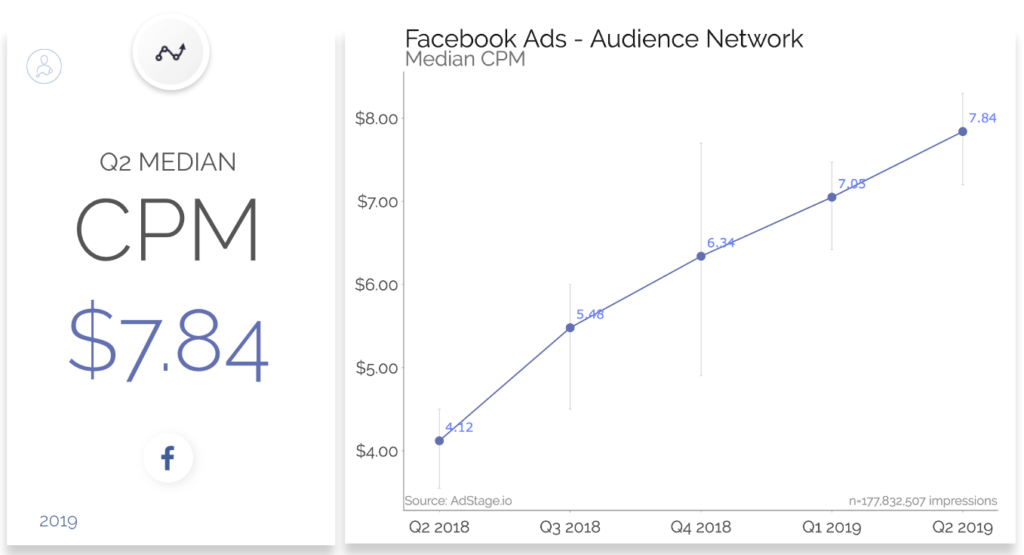

They’ve built dominant presences in Google’s search results, turned their Instagram followers into micro-influencers, and used highly targeted Facebook ads to grow their audiences.

They’ve shown extraordinary resilience amid the Covid-19 pandemic. Not only have these direct-to-consumer brands survived the crisis, but many also kept growing and winning new customers.

But what sets these brands apart from traditional retailers?

What is Direct-To-Consumer Retail?

Direct-to-consumer (or D2C) companies manufacture and ship their products directly to buyers without relying on traditional stores or other middlemen. This allows D2C companies to sell their products at lower costs than traditional consumer brands, and to maintain end-to-end control over the making, marketing, and distribution of products.

Unlike their traditional retail competitors, D2C brands can experiment with distribution models, from shipping directly to consumers, to partnerships with physical retailers, to opening pop-up shops. They don’t need to rely on traditional retail stores for exposure.

These well-positioned startups are competing with some of the biggest retail brands in mattresses, razors, shoes, and more by rethinking not just the product, but the entire retail model.

Casper is taking on the mattress industry; Dollar Shave Club and Harry’s are taking on the razor industry; and LOLA is dismantling the stigma surrounding feminine care and sexual health products. Some of these D2C companies, like Soylent, are building entirely new categories of products.

Of course, in this space, no e-commerce company stands taller than Amazon, and every e-commerce company must factor the company into its growth strategy. These companies have figured out how to use Amazon for (partial) distribution of their products or carved out niches away from Amazon‘s marketplace.

In this analysis, we examine how these once-tiny startups have made it big. We identified 4 broad areas where these companies set themselves apart — in design, how they launch, the customer experience they build, and how they market themselves.

Below, we’ll show you the lessons exemplified by the best D2C companies:

Lesson #1: When it comes to product design, simplicity is the new luxury- How Casper first sold $100M in mattresses by limiting choices

- Why rolling back razor evolution got Harry’s 1M customers in 2 years

- The simple, unadorned sneaker that makes Allbirds a $1.7B company

- How Bonobos turned one good pair of pants into a $310M business

- How BarkBox built a $150M+/year company with one simple box

- The pair of shorts that helped Chubbies become a $40M/year business

- The engineering problem that pushed Bombas to $100M in annual revenue

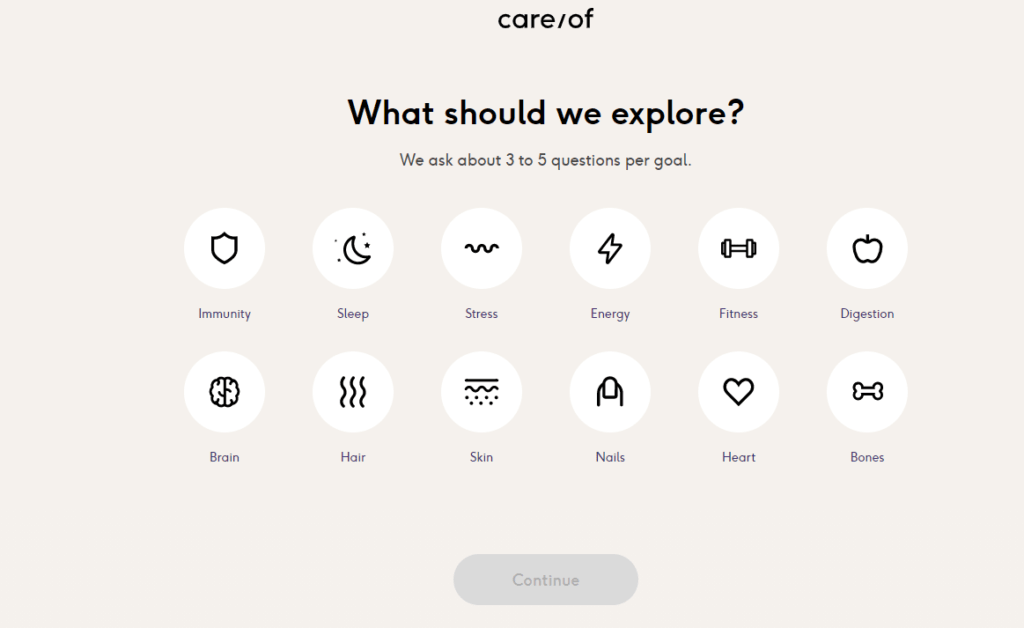

- Care/of made getting personalized vitamins as easy as taking a quiz

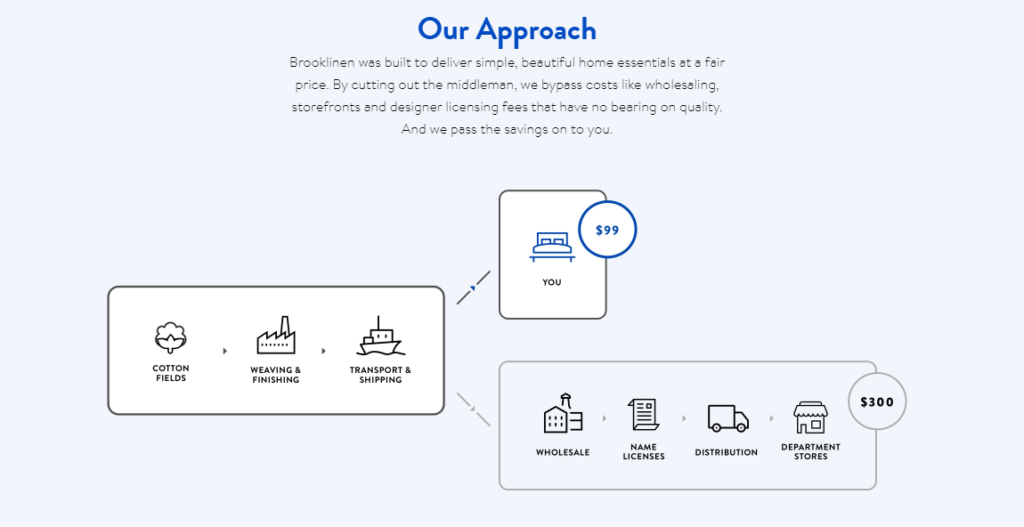

- Cutting out the middleman allows Brooklinen to made luxury goods affordable

- Lesson #2: Building an audience quickly is vital for product launch

- Casper’s media company strategy for redefining the mattress brand

- How Harry’s signed up 100,000 people to a new razor’s email waiting list

- The blog-first strategy that got Glossier 1.5M potential customers at launch

- Why The Honest Company’s Jessica Alba is the best kind of celebrity founder

- How Soylent built a food replacement that sells like a SaaS product

- How BarkBox grew its customer base to 600,000 on a shoestring

- How Bombas pitched its sock business as a mission

- How Gymshark used influencer marketing to grow a cult-like following among gym-goers

- Lesson #3: Building an end-to-end brand starts with a great customer experience

- Why Bonobos aims for (and hits) 90%+ “great” ratings on all their customer service emails

- The 36,000+ subscriber community of obsessives that has fueled Soylent’s growth

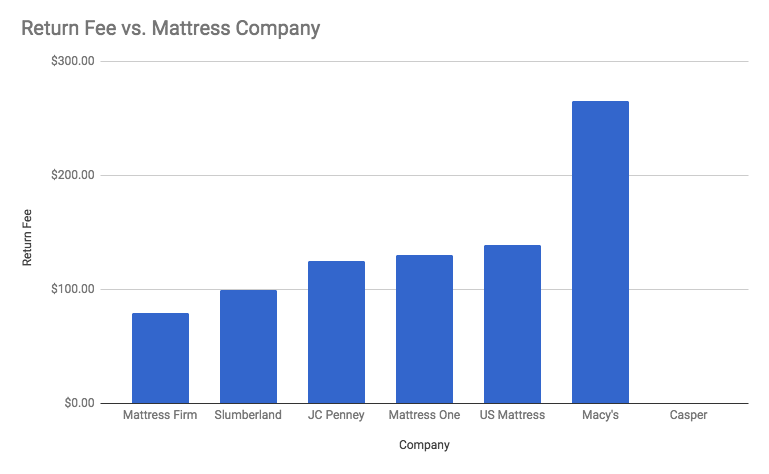

- Why Casper makes it $100-$200 cheaper to return their mattresses

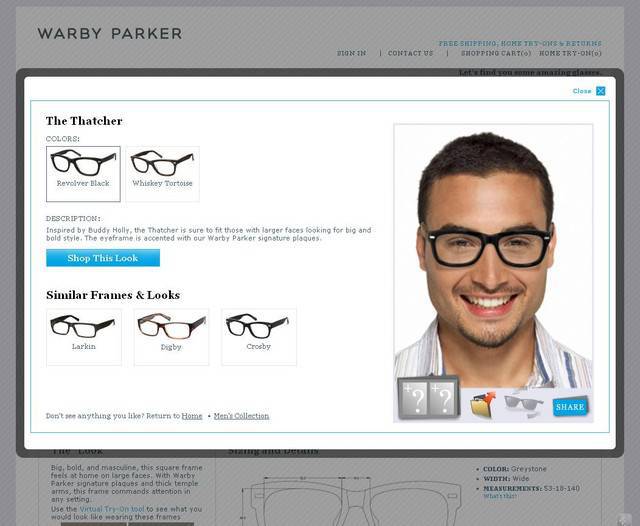

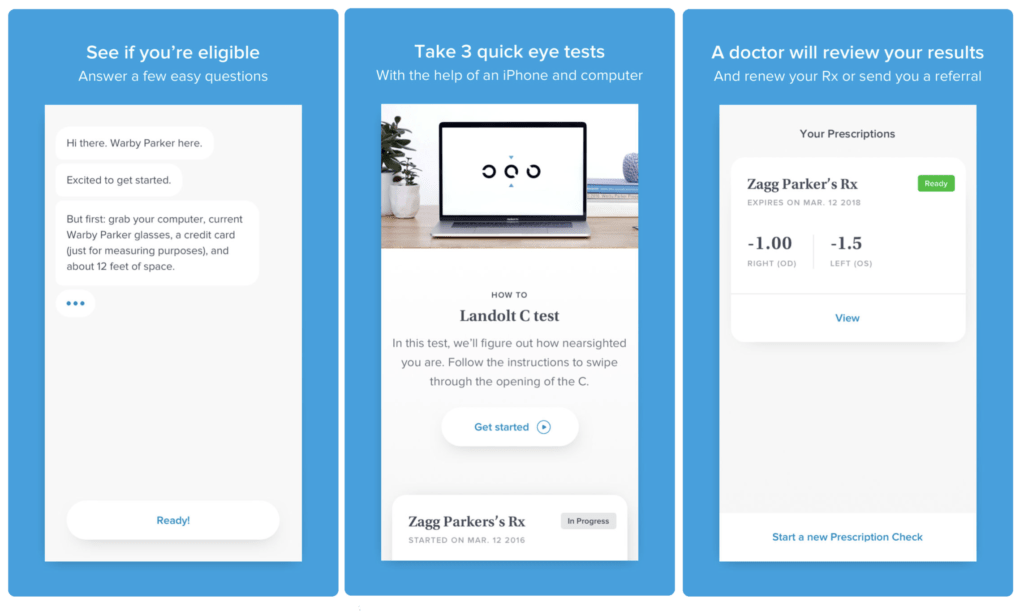

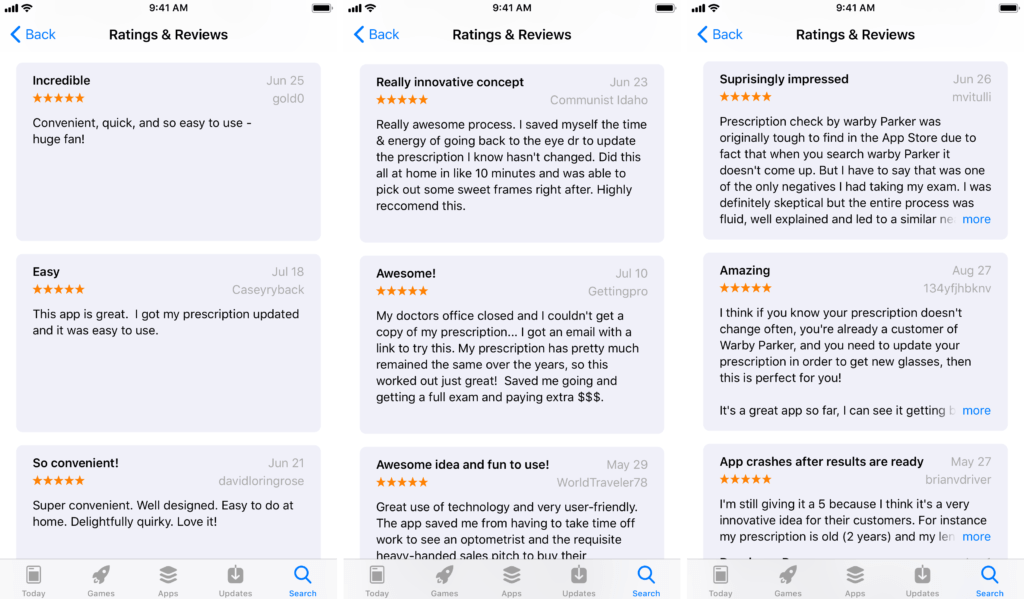

- Warby Parker’s plan to disrupt the $5B eye exam market

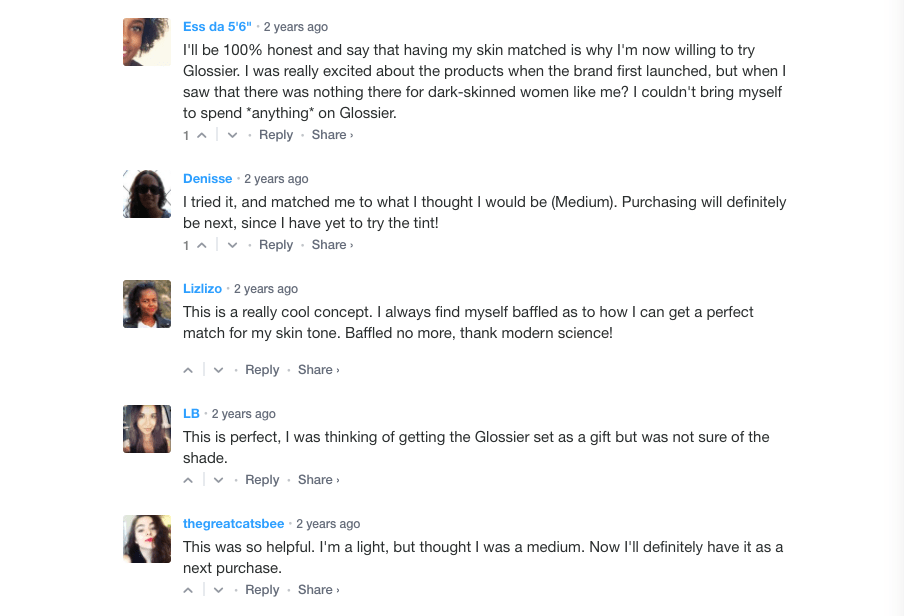

- How Glossier’s skin tone matcher drives online conversions

- The $100M audience that MVMT reinvented the watch for

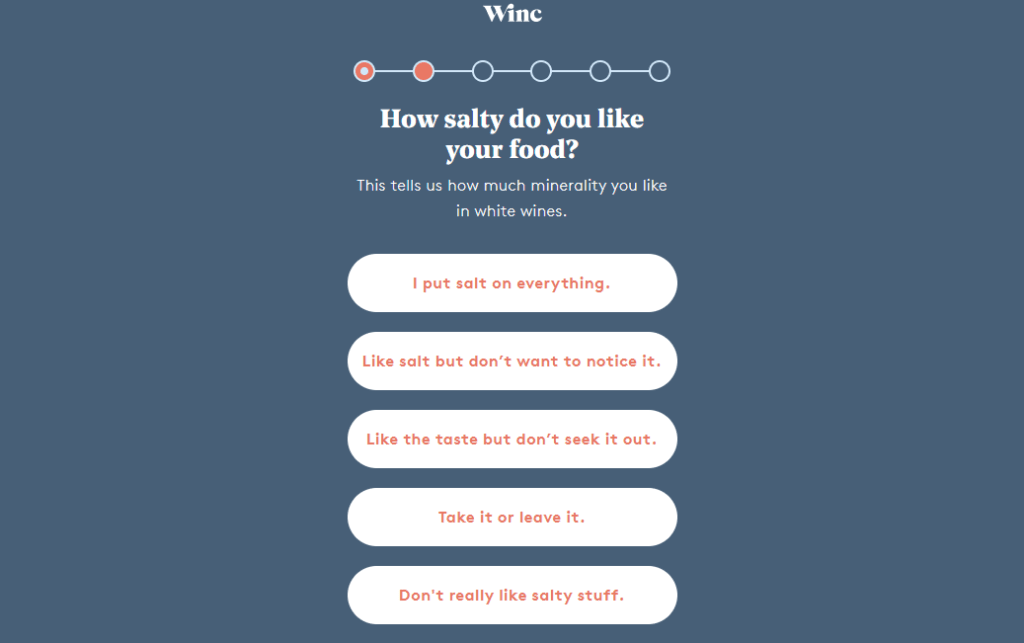

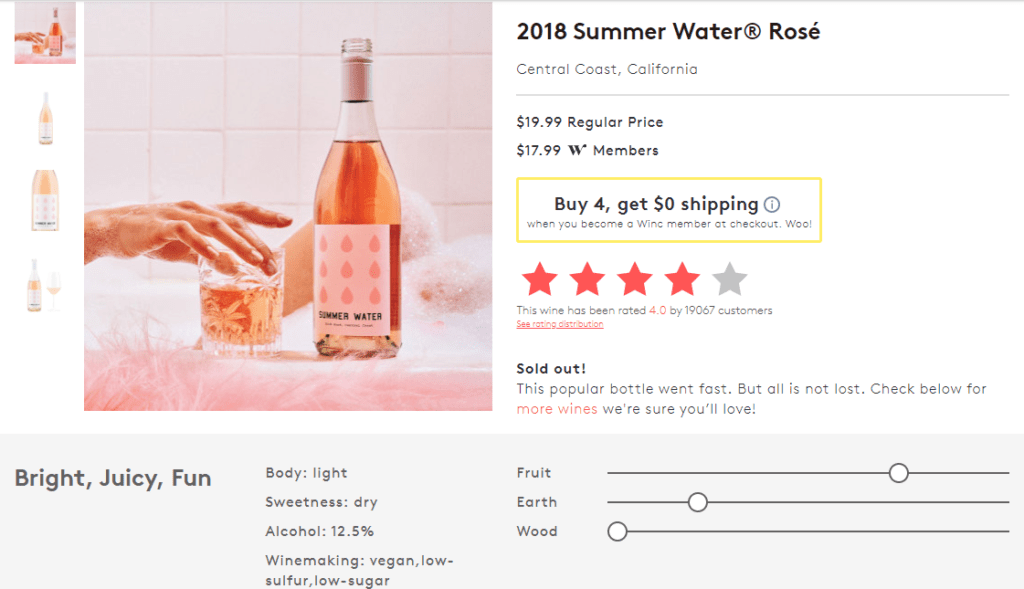

- How Winc reverse-engineered the vine production to revitalize its business

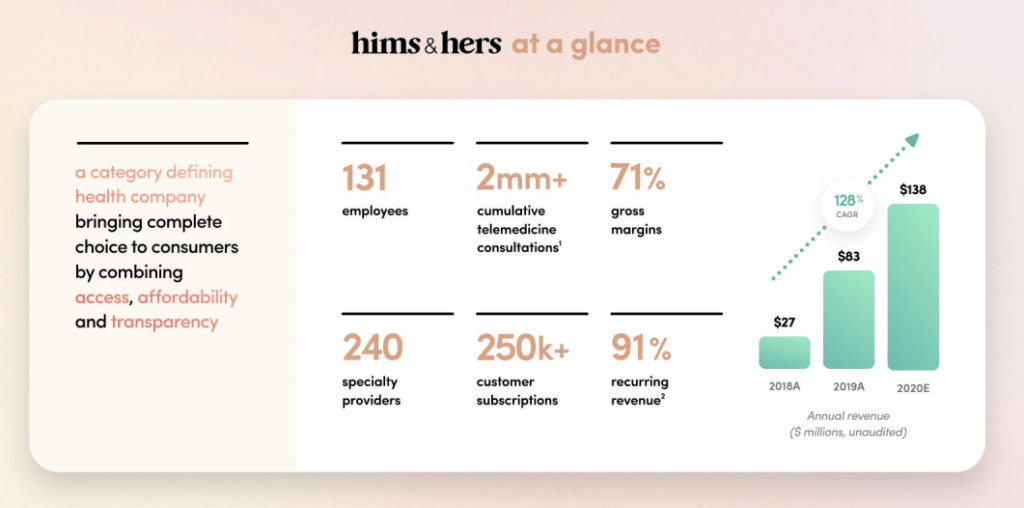

- Hims & Hers wins customers by helping them skip the trip to the doctor’s office or pharmacy

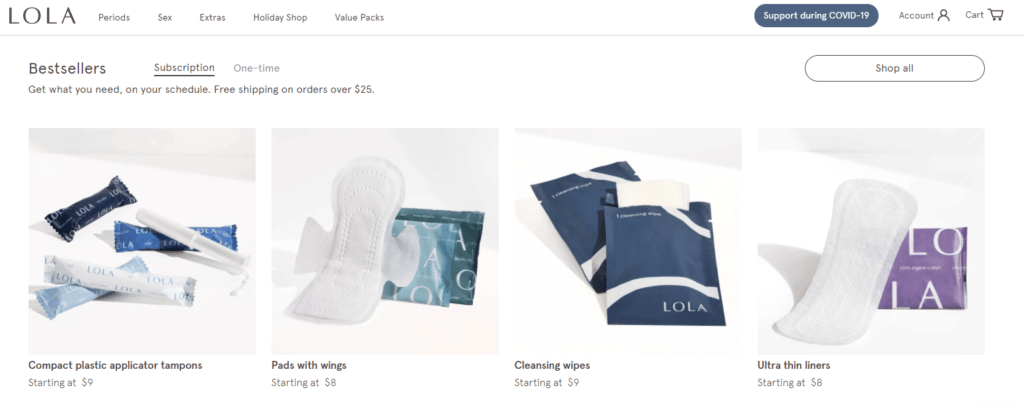

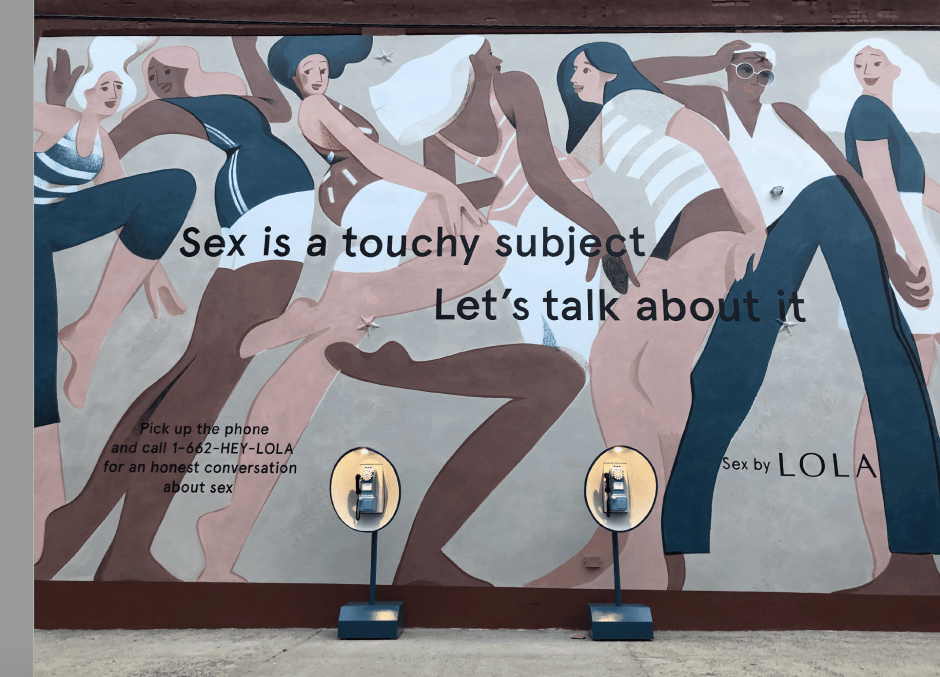

- Dismantling stigma about feminine care and sexual health helps LOLA bond with customers

- Lesson #4: Ubiquity and virality are crucial for sales of physical products to take off

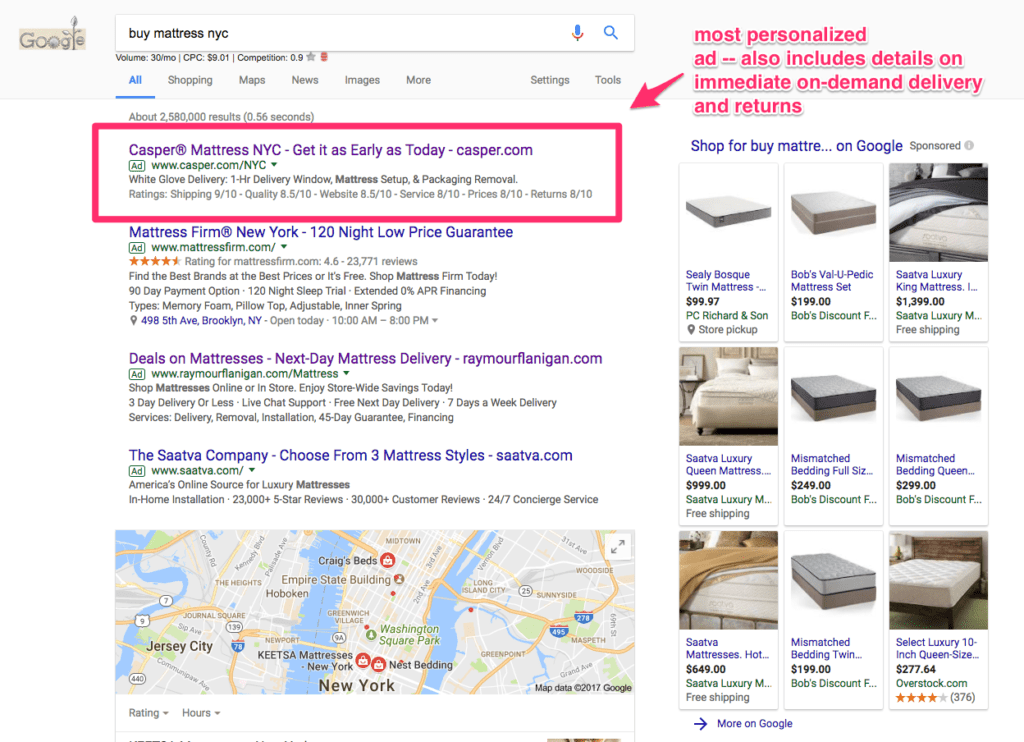

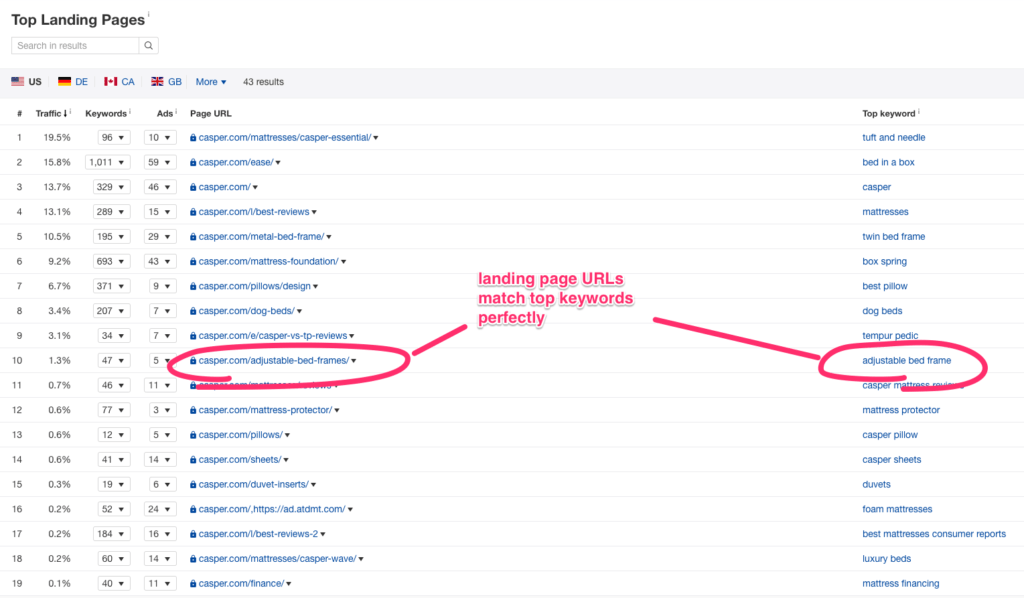

- Casper’s aggressive SEO strategy to stay on top of 550,000+ monthly mattress Google searches

- The strategy behind Dollar Shave Club’s million-view viral video

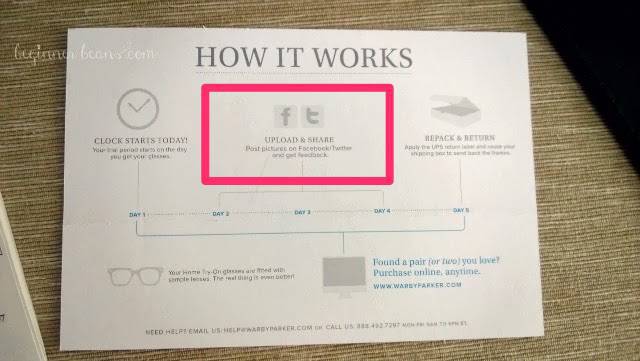

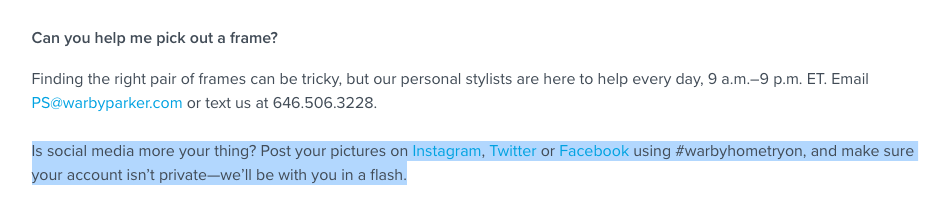

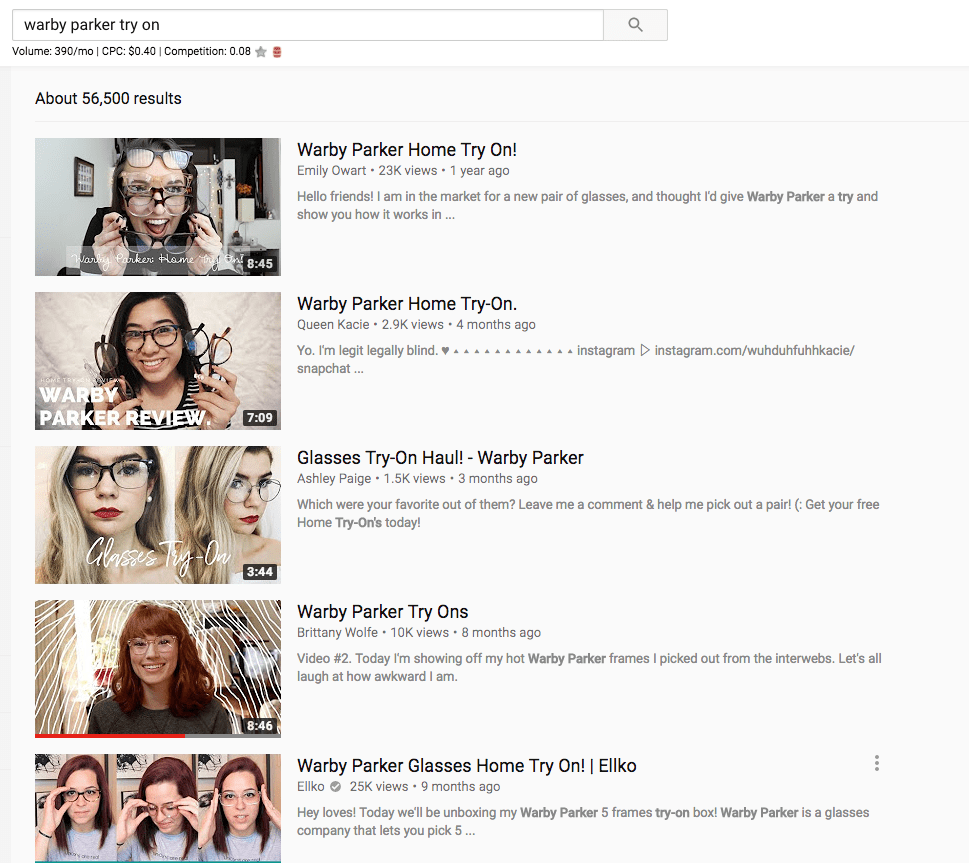

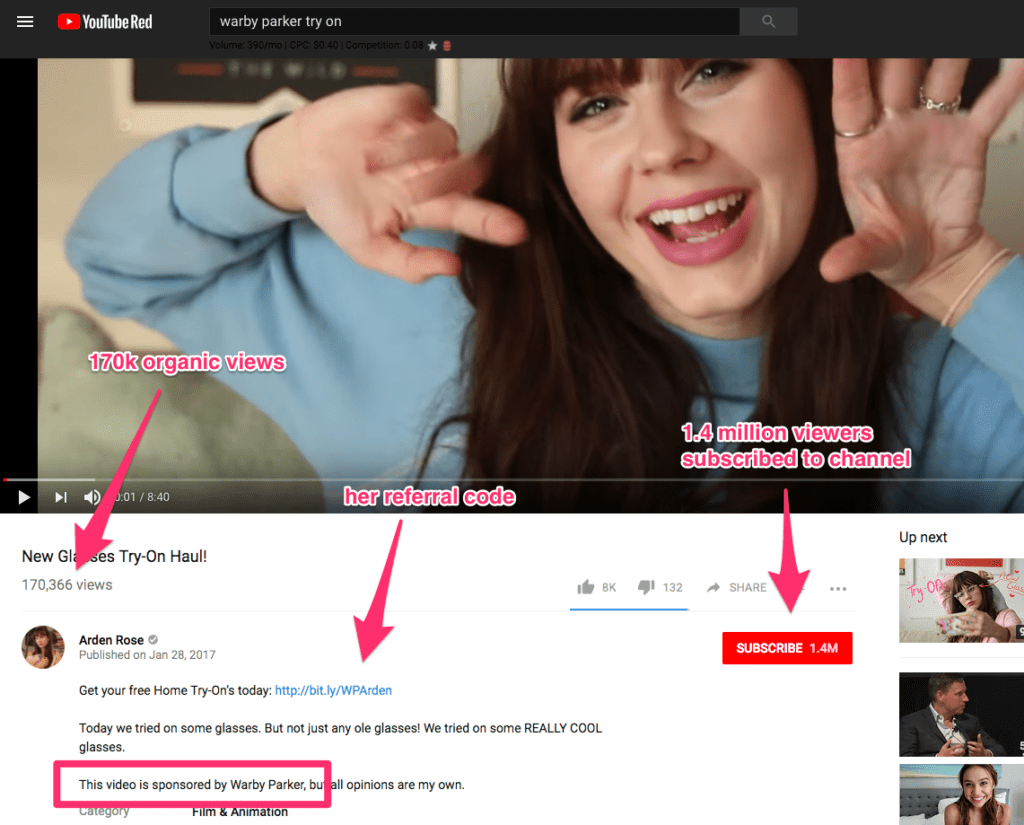

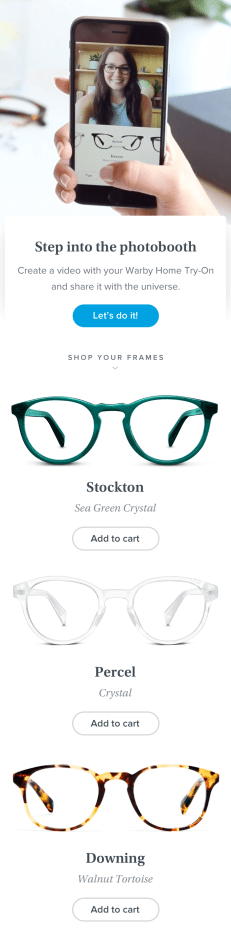

- How one CTA drove thousands of user-generated videos that all linked back to Warby Parker

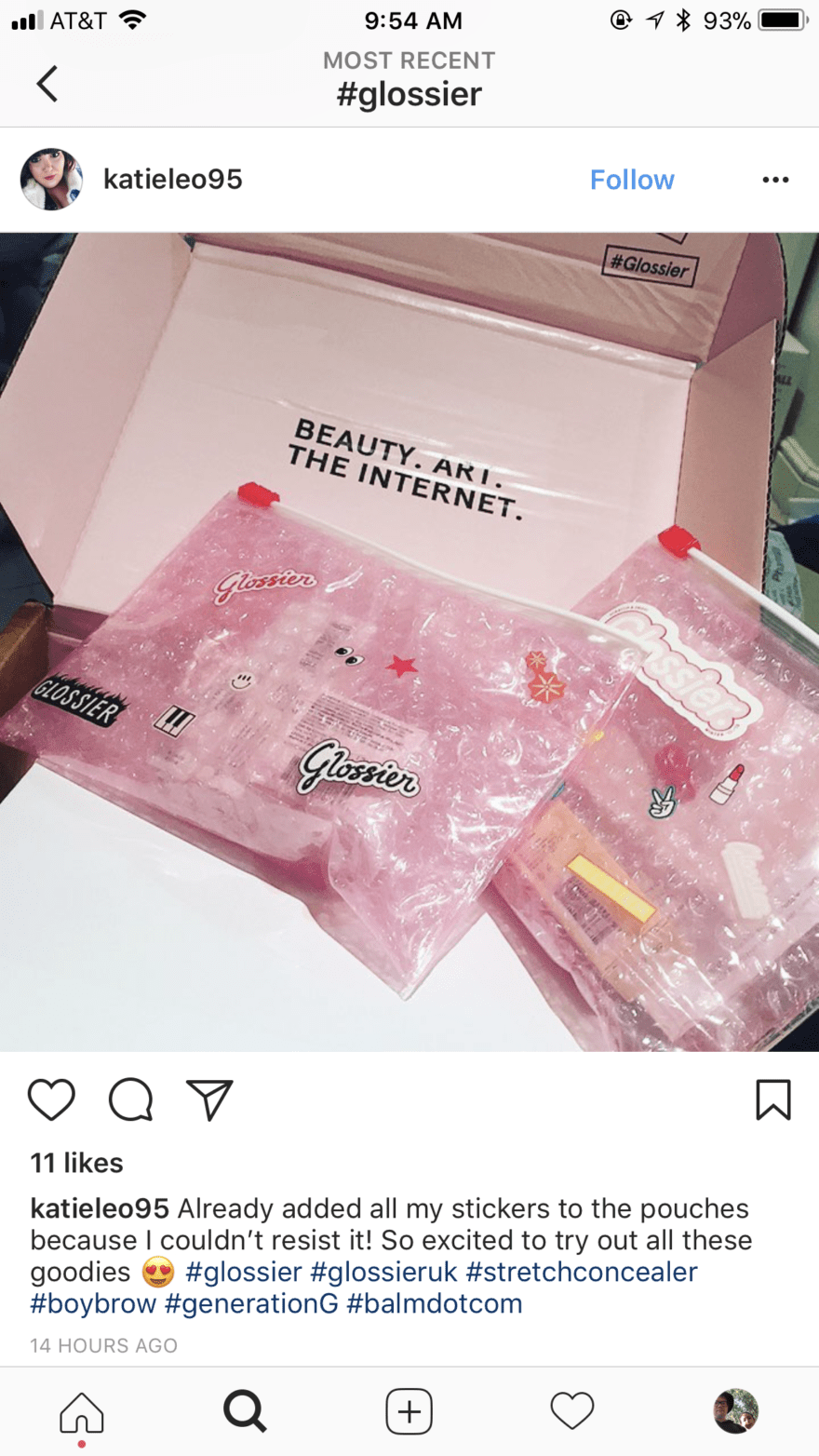

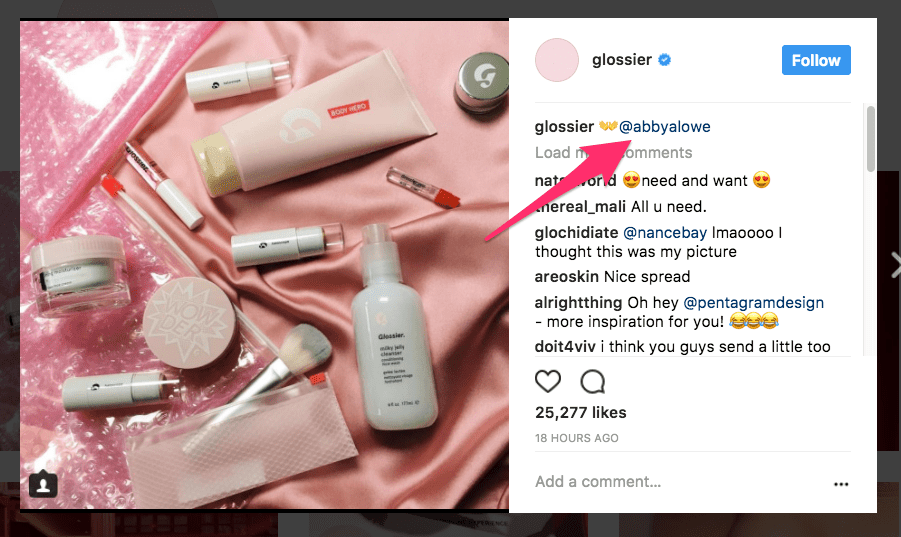

- Glossier’s pool of 2.7M micro-influencers and how they drive 70% of the company’s growth

- The single infographic that got Everlane 20,000 new fans and helped them sell out of t-shirts

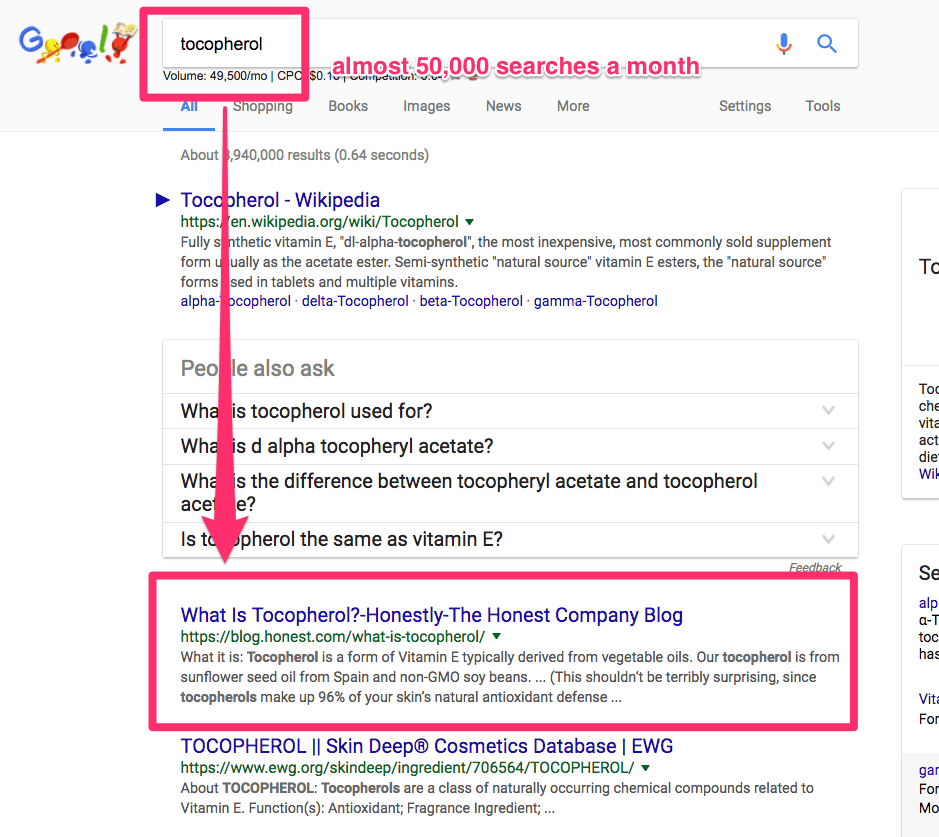

- The Honest Company’s content marketing strategy that secures 100,000+ visits from pre-qualified customers

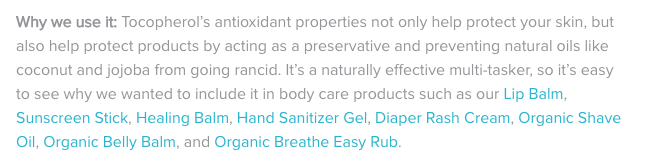

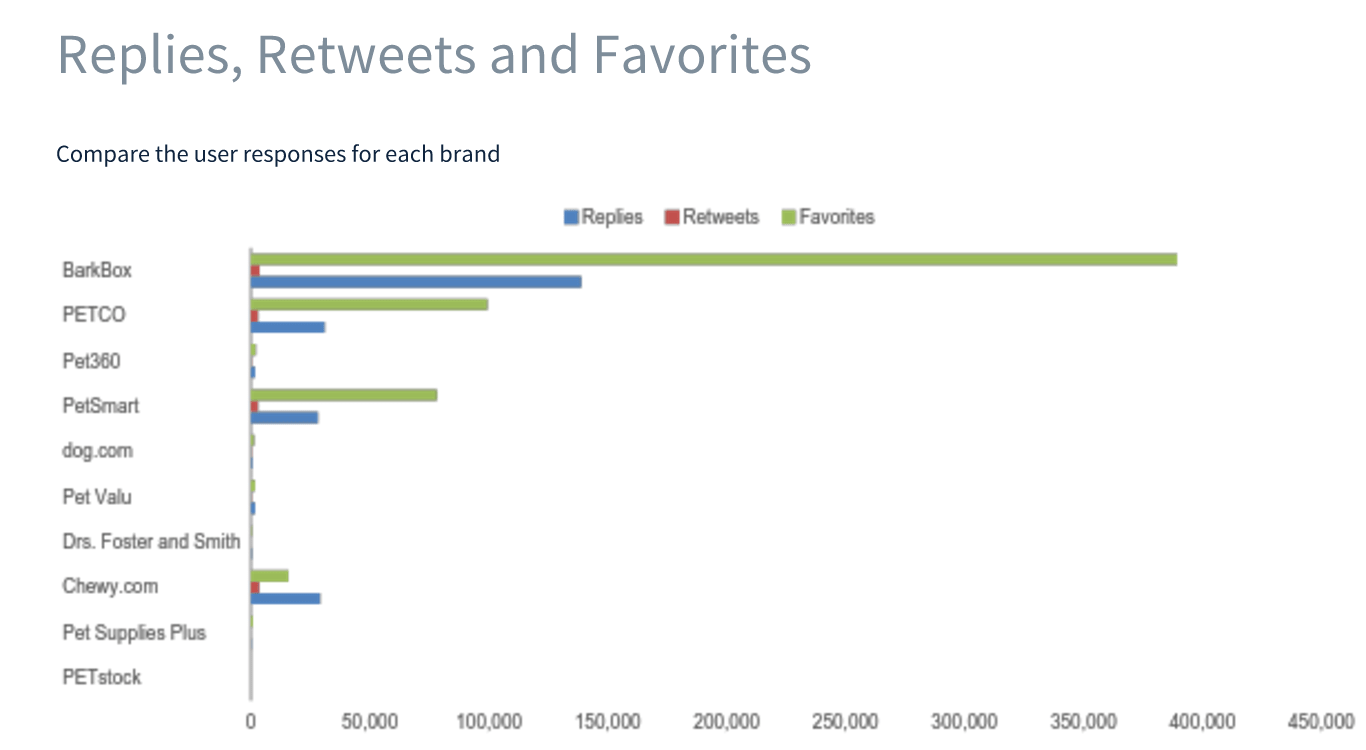

- How BarkBox used humor as a competitive advantage

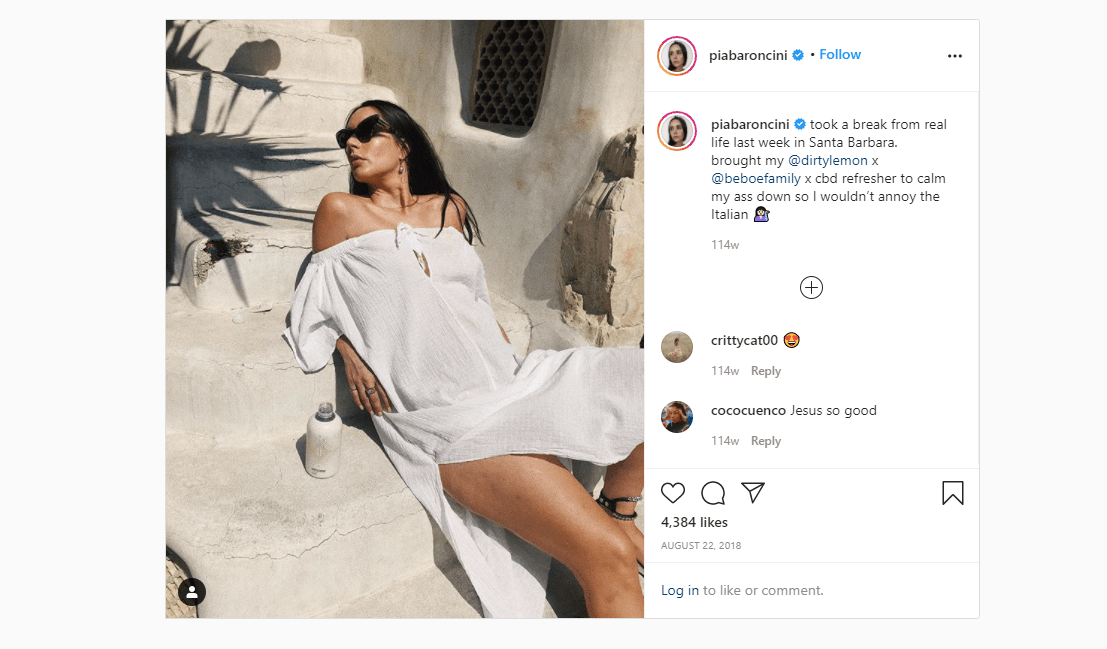

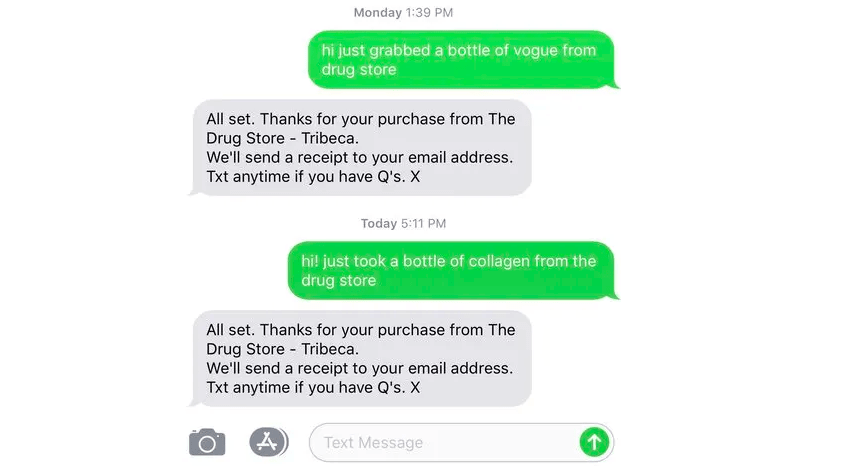

- How SMS sales and cashierless stores set Dirty Lemon apart from the crowd

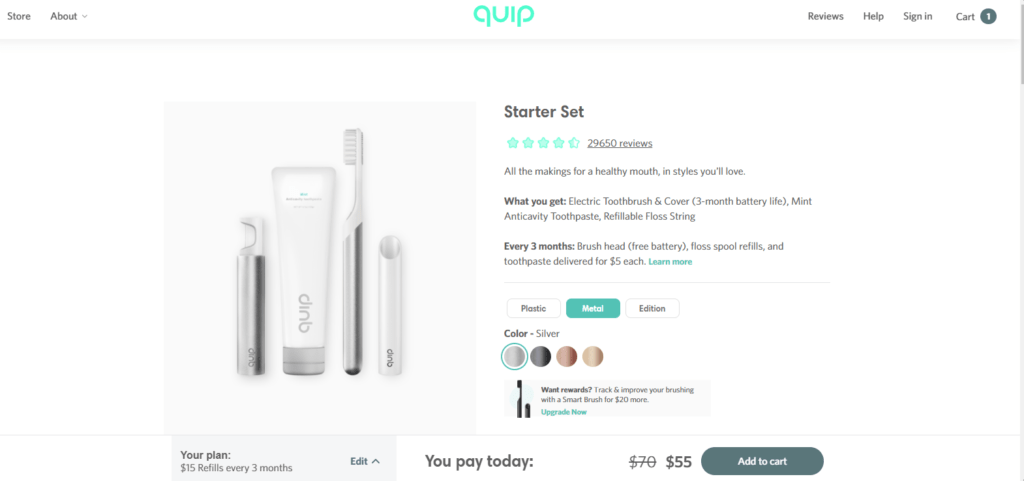

- quip keeps growing by constantly reinventing its marketing strategy

For each company, we combed through CB Insights data, public interviews, product sites, financial documents, news articles, and user reviews to understand just how these companies have built million-dollar, loyalty-inspiring brands.

What follows are the results of our analysis — the best practices for building a highly successful D2C retail company.

Lesson #1: When it comes to designing products, simplicity is the new luxury

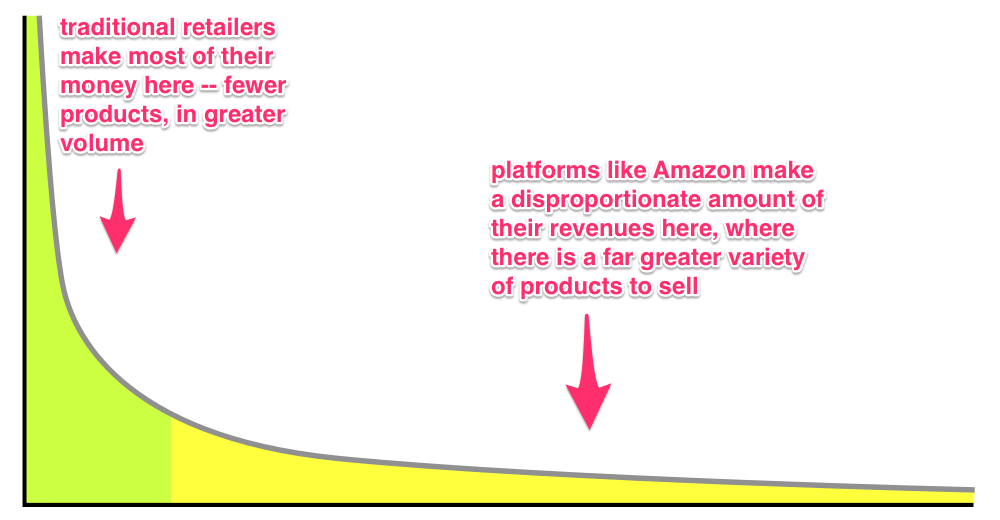

Before the internet, the majority of retailers (aside from mail-order companies) were limited in what they could sell by the amount of shelf space they had. That incentivized them to stock the most popular items and cut those that underperformed.

In 2004, Wired editor Chris Anderson first began writing about how the internet would change this. Since e-commerce companies didn’t have to think about “conserving shelf space,” Anderson argued, they wouldn’t have to make such decisions about what to stock. More importantly, they didn’t have to limit themselves to what was trendy or what sold the most.

They could instead mine the “long tail” of products that didn’t normally get placed in brick-and-mortar locations. Music stores could sell millions of artists’ CDs. Bookstores could sell millions of different books. And doing so would, in the end, be far more profitable than the brick-and-mortar approach.

Today, the world’s dominant retailers are all online. The long-tail playbook has won. But the fastest-growing D2C brands aren’t following it.

Most of the D2C companies that we studied focus on selling only a handful of different products and many started out with just 1. Casper began by selling what its founders thought was a “perfect” bed. Bonobos started with 1 pair of men’s pants. Harry’s started with 1 type of razor — 5 blades, plus one for trimming.

It’s a way to cut through the noise and get people’s attention, to brand your product as “the best.” With so many options available on a site like Amazon, selling just one is a prestige move that establishes that “no alternatives will do.”

It’s also a prudent move: only selling one product lets you pivot back to the drawing board and make adjustments as you get feedback from your early adopters. You don’t have to burn all that inventory and eat the costs. You can more easily make tweaks and get V2, V3, V4, and so on out there.

To succeed, startups have to use speed and data as an advantage. They have to be willing to fail quickly and change the direction of the entire organization if necessary. Selling just one product — and focusing on making it great — is how CPG companies accomplish that.

The success they’re having suggests many consumers agree with their ethos — that sometimes, less is more.

Casper: How to sell $100M of mattresses by limiting choice

The bed-in-a-box startup Casper launched in 2014 with 5 co-founders and 1 fundamental observation about the mattress industry: that buying a mattress is an “awful consumer experience.” The salespeople are pushy, the prices are high, and the different options are confusing.

Their goal was to build a mattress company that was different in every way:

- Just 1 model of bed

- At an affordable price

- Delivered straight to your house

In less than 2 years, Casper had done $100M in sales.

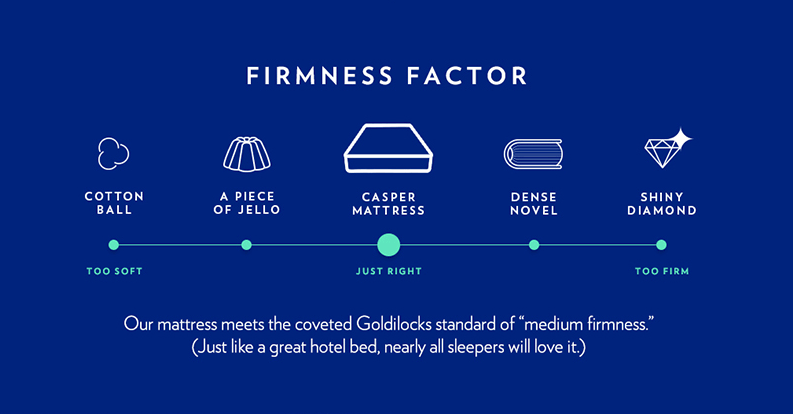

The promise that shaped the Casper brand in the early days was simple — it made one mattress, and it’s the best. No need to choose.

With just one mattress, Casper had to find the level of firmness that would be the most comfortable to the largest possible market.

With just one mattress, Casper had to find the level of firmness that would be the most comfortable to the largest possible market.

Some of this meant revisiting conventional wisdom around how we sleep. One example was the idea of “sleep positions.” As co-founder and COO Neil Parikh told Architectural Digest, “busting this myth” helped reinforce the idea of selling just the one mattress. He noted, “For a long time we’ve been told that everyone is either a side sleeper, a back sleeper, a stomach sleeper, that’s it… But we were watching a lot of people sleep, [and] it turns out that most people shift positions throughout the course of the night.”

People typically shift their sleeping positions during the night.

In other words, companies had sold consumers different products for different preferences that didn’t really exist. “It turns out that [just] one product works for most people,” he said.

Choice is built into how consumers think about many types of products, but companies like Casper endear themselves to their customers by actually eliminating “unnecessary” choices.

In 2014, the New York Times published a 2,200-word piece about the “Kafkaesque” process of trying to buy a mattress. In it, they place the blame directly on this notion of “choice” — if you can call it that. While trying to understand the difference between mattresses sold at different brick-and-mortar mattress retailers, the writer is told by a salesperson that even differently named mattresses may be identical from store to store. There’s no way to know, as the author concludes:

“It’s difficult to comparison shop because many manufacturers sell exclusive lines to retailers. So the mattress you like at Costco may not be carried at Sleepy’s — or if it is, it’s called something else. After she found a mattress she liked in one store, Ms. Judelson said: “I’d go into store B and say, ‘Do you have the Serta blah, blah, blah?’ And the salesperson would say: ‘I don’t know. We may. But ours have different names.’ ”

In 2020, when you search for mattresses on MattressFirm’s website, you have a total of 388 options.

While the traditional mattress brands and physical retailers were playing a game of confusing choices and high prices, Casper set out to fight the idea that multiple types of mattresses are even necessary.

To do this, the company did its research.

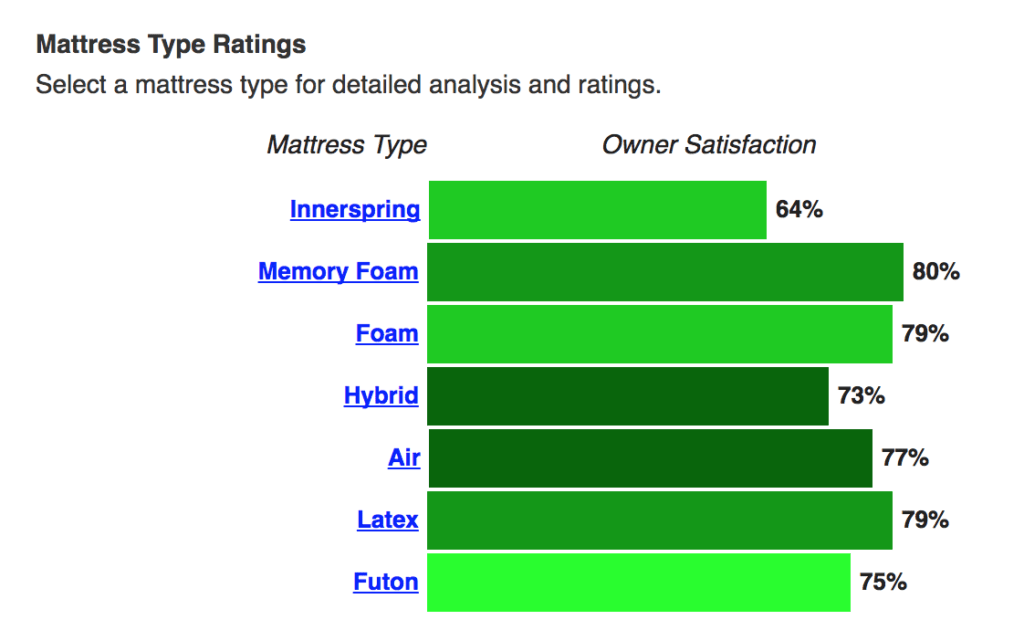

They found out that there are 2 mattress materials that consumers tend to prefer above others — foam and latex — and when combined, they produce a solid all-around mattress.

Some people would still prefer air, or innerspring, but losing those potential customers would be worth the logistical simplicity of only selling one kind of mattress.

User rankings for various types of mattress materials. Source: Sleep Like The Dead

It was a strategy that helped get Casper to $1M in sales its first month and $100M within its first 2 years. The company also went public in 2020, although at a share price well below its expectations.

A similar strategy was followed by another back-to-basics company, Harry’s Razors. Just as Casper had hundreds of years of mattress evolution to learn from in coming up with the “one perfect mattress,” Harry’s knew razors had gotten unnecessarily complicated over the years. The company’s goal wasn’t, however, to roll all that evolution back — it was simply to revert back to the model that had gotten it the most right for the majority of consumers.

Harry’s: How rolling back the razor got Harry’s a million customers in 2 years

Harry’s started out of the same kind of frustration that fueled the birth of Casper: founder Andy Katz-Mayfield went to the grocery store to stock up on blades and mulled over the absurdity of the process:

- He had to find the razor section in the store, and then request an employee to come and open up the locked case

- From that case, he had to choose from among dozens of seemingly undifferentiated models with names like “Turbo” and “Mach”

- He wound up paying a total of $25 — for 4 blades and some shaving cream

He called his friend Jeff Raider (who’d previously co-founded Warby Parker: more on them later) and they decided to start a razor company with a simple model: one great razor, with cheap blades, delivered straight to your door

They started out with an inventory of 10,000 razor handles in March 2013 and sold out within a few days. Two years later, their company was worth $750M, and in 2018 it generated about $270M in sales. And all of this was built, in large part, on the idea that consumers don’t really need as much choice as they’re being offered when it comes to razors.

The idea of having a wide range of choices is central to the traditional razor shopping experience, but Harry’s proves this isn’t what people want.

The idea of having a wide range of choices is central to the traditional razor shopping experience, but Harry’s proves this isn’t what people want.

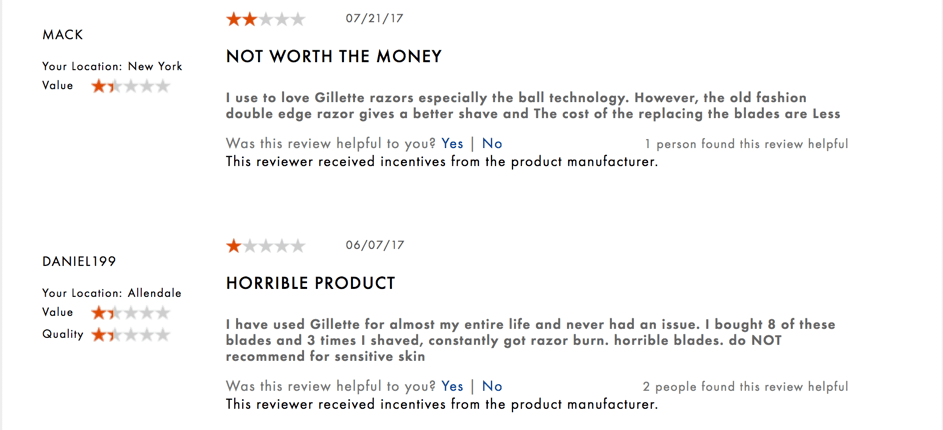

The strategy stood in contrast to the earlier marketing practices of razor giant Gillette, which was acquired by P&G for $57B in 2005. The company was known for a long time for launching a slew of new products and hyperbolically calling each one “the best.”

It was also known in the past for the practice of steadily increasing its prices. Since launching in the early twentieth century, prices on Gillette blades went from pennies a piece to as much as $6 a blade (though Gillette eventually lowered its prices and created new distribution models). It’s a strategy that has been so effective at helping Gillette build dominance that it has become well-known to MBA students everywhere, as the “razor and blades” business model.

According to power law, “the 14-bladed razor should arrive in 2100,” The Economist wrote.

Harry’s instead cultivated a brand that embraces simplicity. It only sells one type of blade, and refills come in at about $1.87 a cartridge. You can get a rubber handle to put those blades in for $9, or upgrade to a metal one for $20. That’s pretty much it. It’s relatively narrow compared to the product line of a company like Gillette, which is exactly the point.

Two reviews on blade refills for the “Chill” subset of the “Proshield” subset of the Gillette Fusion line evince customer frustration.

The single razor option that Harry’s offers, however, actually borrows something crucial from Gillette — it uses the same “optimal” number of blades.

Every Harry’s razor has 5 blades, plus an extra one on the back for trimming in tighter spaces — the same blade quantity and layout as that of the Gillette Fusion5 first released in 2006.

Where Harry’s sets itself apart is in all the new models and new features it chose not to layer on top of that basic 5-blade model.

While Dollar Shave Club (more on it later too) tells you its blades are “f***ing great” and Gillette brands its razors with names like “Mach” and “Turbo,” Harry’s uses a more subtle, affable kind of brand voice. On its social media posts, the company says that “Unlike the big brands that overdesign and overcharge, we make a high-quality shave that’s made by real guys for real guys.” And the owners hone in on this message, saying, “We’ve built Harry’s to reflect our passions and values: affinity for simple design, appreciation of well-made things, and a belief that companies should make the world a better place.”

This “guy’s guy” branding is key to the ultimate success of the Harry’s model. It’s not enough to just make only one razor. You need to convince people that the one razor is actually preferable to the other company’s razors. By offering fewer options, Harry’s was able to convince customers that they need look no further for the best razor.

Building on that success, the company eventually expanded into adjacent products. Harry’s now offers men’s face wash, shower, and hair care products, along with accessories such as toiletry bags. It also launched a women’s brand, called Flamingo, that sells razors, gels, lotions, wax kits, and more.

As sales burgeoned, the company caught the interest of Edgewell Personal Care, an established consumer products giant. Edgewell proposed to buy its D2C rival for $1.4B, but the acquisition didn’t go through because the US Federal Trade Commission (FTC) argued the deal would harm competition.

The company’s marketing and product prowess served it well during the Covid-19 crisis, as it’s experienced a spike in demand.

Allbirds is another great example of a startup successfully putting out a simple product in a field dominated by larger, better-established brands. Here, however, the lesson has more to do with branding and signaling.

Allbirds: How cutting sneaker feature creep let Allbirds 4x its first-year sales projections

Before Phil Knight started Nike, he was importing Onitsuka Tigers sneakers from Japan and selling them to collegiate sprinters. He was a runner, and he knew from experience that they were a much better running shoe than what was available in the US at the time.

As time went on, Nike started selling shoes meant for all sorts of different contexts — basketball, football, skateboarding, golf, wrestling, etc. By contrast, Allbirds, which was founded in 2014, started off selling one type of shoe.

That’s by design, as Allbirds co-founder Tim Brown explains: “The insight that kicked this whole journey off was, ‘Could you make a very, very simple sneaker that wasn’t adorned with branding?’ It felt like it was very, very hard to find.”

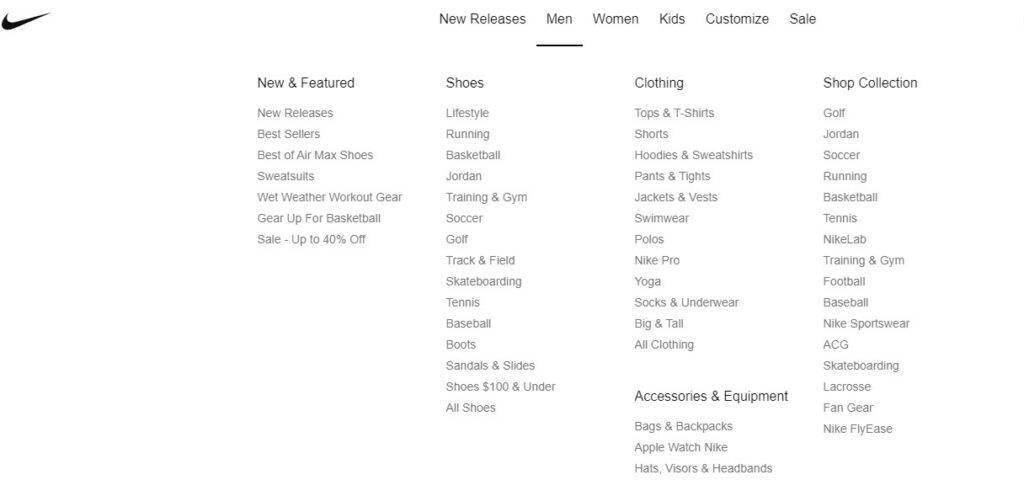

In 2020, there were 16 different collection-based shoe categories on the Nike site, 13 activity-based categories, 16 athletes-based categories, and 11 sport-based categories.

In 2020, there were 16 different collection-based shoe categories on the Nike site, 13 activity-based categories, 16 athletes-based categories, and 11 sport-based categories.

Nike began by reselling a single type of sneaker to a specific market, but it gradually started broadening its line as well as iterating on each one with new features.

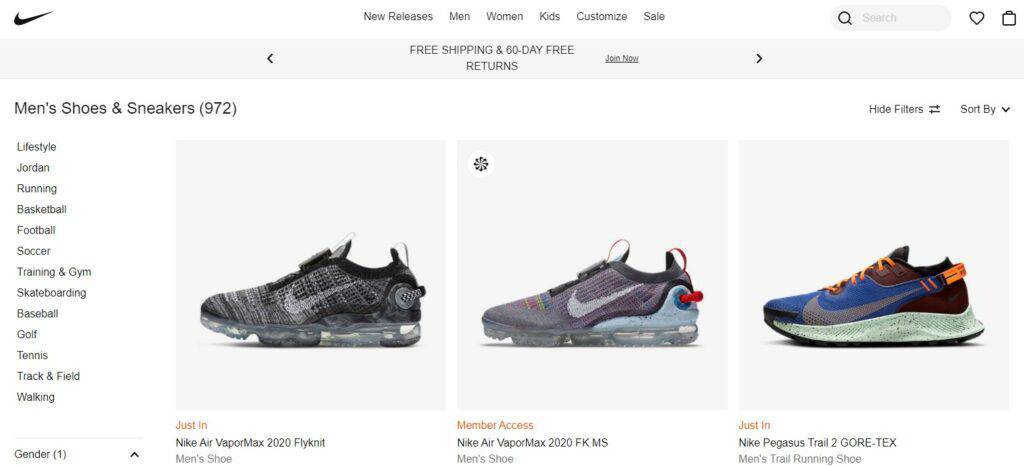

Nike’s website offered 972 different pairs of men’s shoes in November 2020.

Allbirds built its brand around the design of the shoe itself and its nonbranding. The centerpiece of the product is the shape, look, and feel of the shoe.

This ethos helped the company raise its $17.5M Series B in 2017, and later, a $100M Series E in September 2020 at a $1.7B valuation.

The company closed its stores in March amid Covid-19, but that didn’t stop the release of new running shoes called the “Dasher” a month later.

Allbirds’ one-shoe approach found a launchpad in uniform-happy Silicon Valley. Bonobos, the men’s wear brand that launched with one better pair of pants, did too — but it reached far outside the SV bubble by solving a more general problem faced by men in nearly every walk of life.

Bonobos: The $310M brand launched by a single pair of good pants

Founded in 2007, Bonobos is the oldest company on our list of D2C stories. The company, which was acquired in 2017 by Walmart for $310M, launched with a simple premise: make a better pair of pants. Succeeding on that premise gave Bonobos clout with its customer base and kickstarted its growth.

Six months after the company launched, it was doing $1M a year in annual run rate. Eventually, Bonobos would expand to sell formal wear, swimwear, shirts, and many other accessories, focusing on pieces where men traditionally had problems with fit. The company that built its name only selling a single pair of corduroys initially had revenues of $9.5M in 2010 and nearly $70M in 2013.

Andy Dunn and his co-founder started Bonobos with 2 axioms in mind:

- Men do not particularly like going out and physically shopping for pants

- The majority of men have difficulty finding well-fitting pants

In their research, they found that European pants were typically too high-rise and too tight in the thighs for most men, while most American pants were boxy, ill-fitting, and had a lot of extra fabric in the thigh area. That fabric had a tendency to bunch up in the back and give men the appearance of so-called “diaper butt.”

They saw that they could build a pair of pants that fit somewhere in between the European and American extremes, and if they did so, they would have a product worth selling. There are echoes of this model in those of Casper (foam + latex mattresses = a middle ground of firmness) and Harry’s (5-blade razors = a middle ground of closeness).

If they sold just one product, then they could also sell and distribute their product entirely online. They wouldn’t need a brick-and-mortar location at all, and so they could immediately sell at a virtually global scale.

The only problem with this was getting over the hesitancy many people felt about ordering clothes online, especially when — as is true with pants — fit can be so fickle.

Bonobos’ revenue over its first year of sales.

Bonobos’ revenue over its first year of sales.

To solve that, the co-founders copied Zappos and introduced free, no-questions-asked returns. Bonobos encouraged its customers to order multiple pairs and return the ones that didn’t fit.

Early customers raved about the fit and the quality of the pants, helping to build trust as the company introduced a wider product line. “Bonobos Stretch Cotton Pants just blew my mind,” read one early forum review:

“I was recently trying to find a pair of grey chinos to wear casually and thought about Bonobos which is mentioned on Dappered fairly often. I told them the pants I buy usually feel too tight in the crotch area and end up being very uncomfortable. They recommended the Bonobos Robber Barons which were a straight fit pant in their stretch cotton fabric… Holy crap these pants are amazing.”

“[Succeeding] earns you the right to go from product one to product two,” said co-founder Andy Dunn. “Take as much time as you need to get product one right, and to prove it — because if you don’t, no one is going to be waiting on pins and needles for product two.”

Pants allowed Bonobos to tell what Dunn calls a “narrow and deep story” to an audience of early adopters to who it could sell further products down the line. He says that pants got people to care about Bonobos the way ties got people to care about Ralph Lauren and wrap dresses got people to care about Diane von Furstenberg. Pants got people’s attention — and built their company into what it became.

Allbirds’ one-shoe approach found a launchpad in uniform-happy Silicon Valley. Bonobos, the men’s wear brand that launched with one better pair of pants, did too — but it reached far outside the SV bubble by solving a more general problem faced by men in nearly every walk of life.

BarkBox, the subscription toy and treat box for dogs, set out to solve one of the central frustrations of dog ownership for a multi-generational cross-section of pet owners: the overwhelming amount of options available when shopping for your pooch.

BarkBox: The box that launched a $150M a year company

Plenty of retailers in the U.S. are cashing in on the fast-growing $75.4B a year pet products market. Most go broad, trying to offer items for every type of pet, from kittens to lizards to parrots.

Direct to consumer startup BarkBox saw another opportunity. Rather than try to be all things to all pet owners, the startup was conceived to serve just one demographic — die-hard dog lovers — with just its core product: its eponymous BarkBox.

Why a box of dog supplies? Because instead of lavishing attention and money on children, millennials in the modern day are lavishing their attention on their pets. While birth rates among twenty-somethings are at record lows and marriages are also on the downswing, when it comes to pets, millennials are now the biggest market.

And those millennials, increasingly, are anxious for ways to spend their disposable income on their animals — 44% of millennials, after all, see their pets as “starter children,” according to a 2017 study published by Gale, a consumer insights consultancy.

BarkBox founder Matt Meeker saw an opportunity from his experiences shopping for his dog. Consumers walking through your average big box pet store are beset by a big variety of options, and differentiating between them can be challenging.

Spot the difference.

He thought he could improve the experience of buying for furry family members by making it more playful. Instead of picking and choosing from various categories of treats and toys, many of which your dog might not like, BarkBox would offer a monthly delivery with a varying cross-section of goods and samplers.

Each BarkBox includes a selection of toys, treats, and accessories.

He envisioned opening a BarkBox as being an enjoyable experience for both dog and owner — seeking to emulate the surprise and excitement of receiving a gift.

That idea resonated with millennial pet owners. Around 92% of millennial pet owners buy their pets gifts, according to a study by online retailer Zulily. Some of that spending has clearly migrated to Bark, BarkBox’s parent company, which says it reached $375M in annual revenue by September 2020.

“They’ve tapped into that market of consumers that really don’t see the difference between a kid and a pet,” Phil Chang, retail expert, told Industry Dive.

Simplicity has been key to BarkBox’s success. As BarkBox co-founder Henrik Werdelin put it, “Most customers think they want options, but really they want the right options.”

Though there are plenty of other pet subscription services around now, BARK remains one of the leading ones. The company doesn’t release detailed financials, but its projected revenue for 2019 was $250M.

BarkBox’s popularity has continued to grow. It boasts over 600,000 customers and a 95% retention rate — not bad considering attrition is hurting subscription services such as Blue Apron and others. BarkBox has reportedly shipped 10M boxes and 70M toys since its 2011 founding, reaching over 3M dogs. The company reported that overall subscribers are growing even during the Covid-19 crisis. Customers could pause their subscription if they wanted to, but the rate of cancellations in 2020 is similar to previous years.

By focusing on an engaging experience that makes buying fun, BarkBox identified a profitable niche and expanded it. By tapping into a latent, unfulfilled market need, it created an entirely new category. A similar insight birthed Chubbies, another millennial-focused company that offered just one product to a single audience.

Chubbies: The shorts that have driven this $40M/year company’s growth

Started by 4 Stanford grads, Chubbies rocketed from a tiny, bootstrapped startup in 2011 to a direct to consumer trendsetter with $5M in venture funding and reportedly $40M in revenue in 2018.

The secret to Chubbies’ success is two-fold: shorts and the bros that wear them. “Bros” (here referring to approximately 18-34-year-old, athletic men) wear shorts more often than many other demographic groups, and yet before Chubbies, no brand of shorts set out specifically to endear itself to them. By building a brand that was a monument to the “bro,” Chubbies gave themselves an edge over companies like Levi’s and J.Crew.

According to Research and Markets, the men’s and boys’ clothing market in the US generates $121.9B a year. But the shorts segment has historically been left underserved. And like other tuned in retail startups, Chubbies knew how to reach the slice of young men they were targeting.

Chubbies’ tongue-in-cheek “manifesto” even rails against pants, calling them “a necessary evil — built for the work week because your boss just doesn’t get it.”

Chubbies-wearing bros in the wild.

Chubbies shorts are slim cut and come in attention-grabbing colors. One of its bestselling lines is the ‘MERICAs, which sport stars and stripes. The company claims it once sold 10,000 pairs of them in a single day.

The company generated early buzz in 2011 by directly contacting the presidents of fraternities and other college clubs. By the following spring, Chubbies had produced enough shorts to meet their expected demand for the entire summer. They sold out in 2 days.

Today, Chubbies has 5 brick and mortar stores across the Southern US and California. This is part of a larger trend in which formerly online-only brands, like Warby Parker and Casper, have opened retail outlets. Chubbies didn’t report, however, to what extent Covid-19 impacted its retail stores. The brand launched the WFH Collection of shorts with $5 being donated towards Meals on Wheels for each product sold.

But the Chubbies message hasn’t changed. Its clothing is marketed on comfort, nostalgia, and that bro-friendly “feeling you get around Friday at 5 p.m.”

Sock-maker Bombas is taking another approach. Despite its bombastic designs and colorful products, Bombas markets itself as offering a technically-advanced and comfortable pair of socks. The resulting brand is less focused on exuding relaxation, and more focused on showing how Bombas offers a solution to the more annoying sartorial needs.

Bombas: The engineering problem that pushed it to $100M in annual revenue

After its 2013 launch, the D2C sock startup said it was bringing in $4.6M in revenue in 2015, a figure that increased more than 10x to $47M in 2017, and then doubled again to around $100M in 2018.

Bombas is a good example of the kind of product that can leverage the D2C model to great success.

Bombas uses long-staple yarns with antimicrobial and moisture-wicking properties.

Where other sock manufacturers have looked to design to vary their product lines, Bombas wanted to fix the core engineering issues seemingly inherent to most inexpensive socks on the market. It reportedly took co-founders David Heath and Randy Goldberg 2 years of testing to settle on each technical feature embedded in the sock, such as a honeycomb arch support to help distribute pressure and a blister tab intended to reduce chafing.

The company was betting that customers would be enamored enough with the technical aspects of its socks to justify the high $10+ per-pair price tag.

Co-founder Goldberg has likened Bombas’ pricing to that of Starbucks, which managed to increase the ceiling on what Americans were psychologically willing to pay for coffee with a product that resonated with customers. He argues that:

“[Starbucks] improved the quality so much and improved the experience around coffee, that they were bringing the price up to three times what they used to spend. So if it’s 75 cents at a corner deli and it’s $2.25 at Starbucks, you’re willing to pay extra for a better experience, for a better product. And it’s the same thing for our socks” — Randy Goldberg, Bombas co-founder

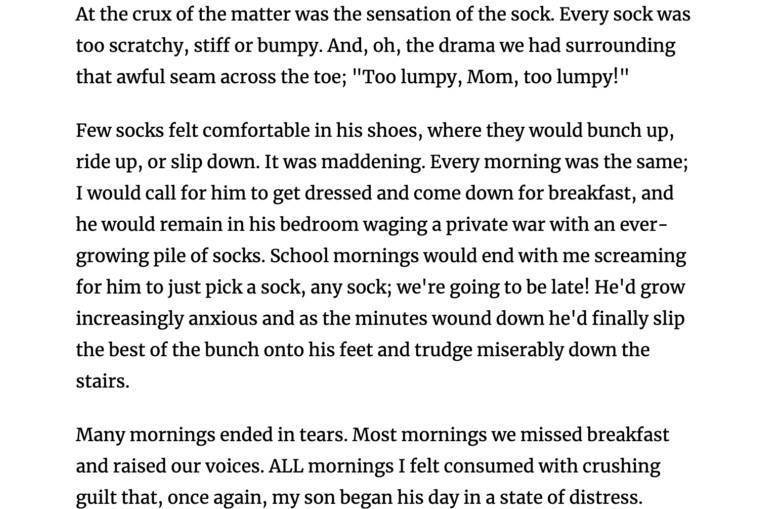

Socks were especially frustrating for co-founder David Heath — he was never able to find a pair that didn’t irritate him in some way, and he resorted to tricks like turning his socks inside out to avoid the toe seam.

Bombas co-founder David Heath did not have a good relationship with socks when he was young.

Heath and Goldberg’s mission to build a better sock has built momentum largely because the problem of uncomfortable, ill-fitting socks is one that many people can quickly resonate with. But to be successful building a one-product company, differentiating on the product itself — as Bombas did — is essential.

Frustrations with existing choices have pushed another entrepreneur, Craig Elbert, into building a better alternative. Together with Akash Shah, he co-founded the vitamin subscription company Care/of in 2016.

Care/of: Getting personalized vitamins is as easy as taking a quiz

Buying vitamins and supplements is a tedious process. Countless choices, lack of guidance, and health buzzwords make it hard for customers to navigate the aisles and identify the products they need.

Elbert was painfully aware of this fact from his personal experience. Buying vitamins for himself and prenatals for his wife proved to be a much more complex process than he expected. He then set out to tackle this problem. Together with Shah, who previously started healthcare startup Hometeam, he launched Care/of. The duo set out to revamp the vitamin buying experience and turn it into a seamless digital journey.

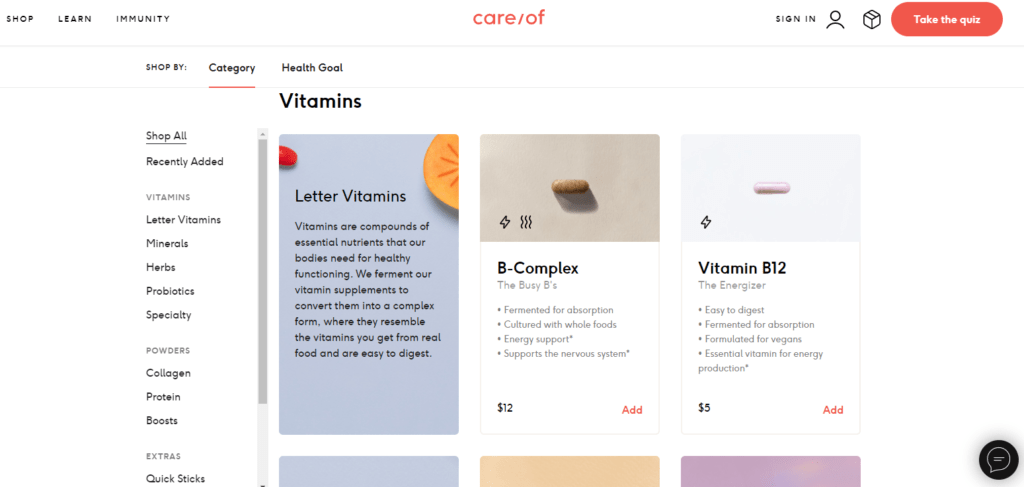

Customers can select a wide range of vitamins, minerals, and supplements online Source: Care/of

Customers visiting the company’s website are first asked to fill out a quiz detailing their age, gender, lifestyle habits, health problems, and diet. From there, an algorithm determines the contents of a personalized pack of vitamins, saving consumers from spending hours looking for suitable products themselves. The selected items are then delivered every month through a subscription service.

Customers are also provided with clinical research sources related to the selected products and their use in traditional medicine. The goal is to set realistic expectations. “Some people are led to believe there is a magic pill,” says Dr. Maggie Luther, ND, Care/of’s medical director and formulator, “so we are trying to provide products that are clinically researched and to provide more in-depth information about the ingredients.”

Designing the product for simplicity and trust proved to be a decisive move. In 2017, the company had 70 full-time employees and raised $15M by that point. A year later, Care/of was valued at $156M after securing investments from Goldman Sachs’ venture capital unit and several other investors. In 2020, the company expanded into the beauty niche, launching a range of products, including ingestible collagen. In 2019, sales skyrocketed 200% year-over-year.

And since 2016, over 5M people have taken the core quiz. They’ve also used the Care/of app to track their vitamin intake and read educational content, providing the company with invaluable insights into customer needs and preferences.

Quizzes are designed to help Care/of suggest vitamins for tackling specific problems Source: Care/of

Such a wealth of data prompted Bayer to acquire a 70% stake in Care/of, valuing the startup at $225M in August 2020. Apart from additional revenue streams, the Germany-based pharmaceutical conglomerate is also getting access to data that can inform its future product and marketing efforts.

And as digital native businesses in the vitamin and nutritional space thrive, brick-and-mortar shops are dwindling down. GNC, for instance, closed thousands of stores over the last several years.

Other industries are similarly abandoning physical locations. Brooklinen is showing that a luxury bedding brand doesn’t necessarily require huge department stores but can instead be built online.

Brooklinen: Cutting out the middleman allows Brooklinen to made luxury goods affordable

Trying to re-create the sleep experience enjoyed in a luxurious hotel in Las Vegas, Rich and Vicki Fulop soon realized that such pleasure comes at a high price. Five-star sheets alone cost at least $800. And weighing quality and price while navigating different stores isn’t easy either.

The husband-and-wife duo also discovered that high-end bedding isn’t necessarily expensive because of material and production cost, but thanks to a vast line of markups from retailers, licensees, and distributors, inflating the end price. Cutting them out and going directly to textile manufacturers could bring the price down without compromising the product quality.

Brooklinen explains its business model. Source: Brooklinen

The Fulops then visited a number of factories. The goal was to find those willing to work with smaller batches. Eventually, the duo decided to manufacture towels in Turkey, sheets in Israel and Portugal, and loungewear in California. But before setting their plan in motion, Rich and Vicki launched a crowdfunding campaign on Kickstarter, bringing in over $235,000.

With a seamless shopping experience, a generous return policy, and quality products, the company flourished. Customers were willing to buy sheets, bedding, towels, and a range of associated items without physically feeling them. Five years since launch, Brooklinen is profitable. It was reportedly on track to make $100M in revenue in 2019. An important factor in this success is that the company “make do without storefronts, slotting fees, distribution, and licensing,” says Rich Fulop. “We’ve cut out all the costs that don’t add value to the consumer.”

The Fulops optimized its products in many different ways. For instance, they discovered that men dislike buying sheets in a store. One reason for that might be the division of household tasks that put women in charge of domestic purchases.

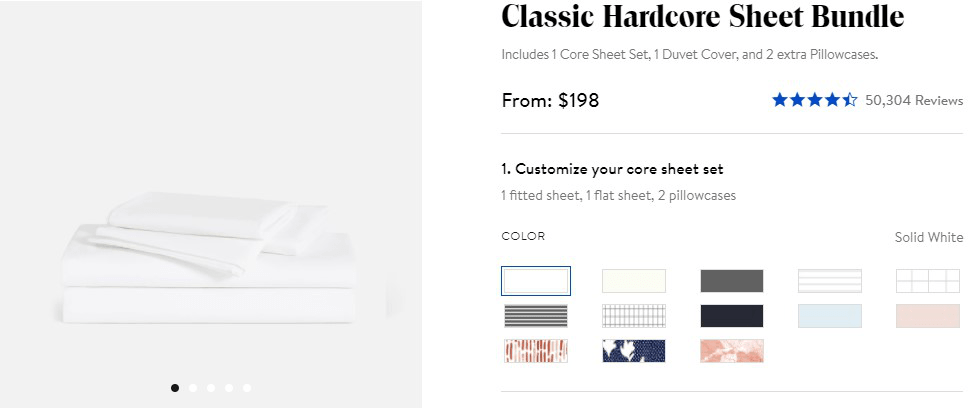

Brooklinen offers a limited number of colors and patterns. Source: Brooklinen

To appeal to men, Brooklinen designed products primarily in gender-neutral colors, such as gray, cream, and blue. Patterns were simple as well, including stripes, windowpane, and grid.

And each sale and customer interaction is carefully monitored. The team analyzes popular products and breaks them down by parameters, such as date, gender, and region. The analysis helps the Fulops decide how many products to produce or where to advertise them.

A customer service team is another source of insights. Support agents engage people who return products, hoping to discover which pattern or color made them unsatisfied. It was through these engagements, for example, that customers voiced their desire for polka-dot patterns. Brooklinen then added this design to its offering, and it became a top-selling feature.

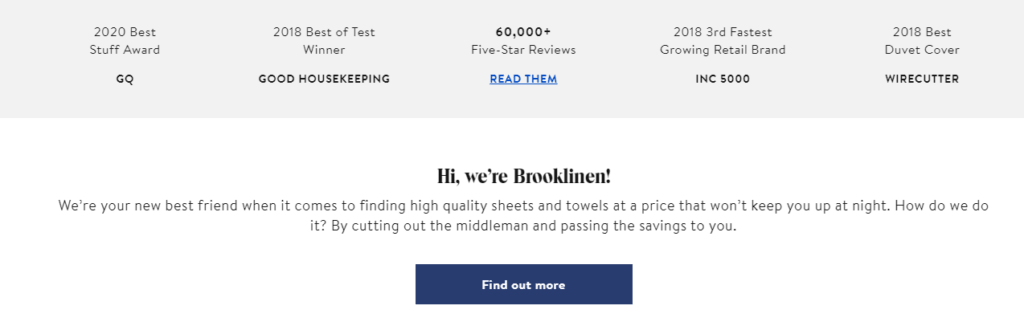

Brooklinen highlights various awards it has won over the years. Source: Brooklinen

The company also discovered that its customers don’t care for embroidery. It then removed this expensive feature from its products and reduced their price. What customers cared about was whether the sheets are soft and made in fair-trade facilities, prompting Rich and Viki to focus on these 2 issues.

Frequent interactions with customers allow Brooklinen to constantly design new products and improve the existing ones. A loyal customer base also kept the business running during the Covid-19 pandemic, despite an initial dip in sales and shipping delays in March and April 2020.

Lesson #2: Building an audience quickly is vital for product launch

When you sell something like a mattress, or a shaving razor, or cosmetics, your total addressable market is huge. There’s no one out there who doesn’t need a bed. Millions of people need to shave.

Because these markets are so big, the brands that dominate them are usually well-entrenched and hard to disrupt.

Successfully entering these markets, therefore, requires establishing a high degree of mindshare very quickly. It means going for “shock and awe” launch storytelling over a more subtle, slow growth strategy. And most of the top D2C companies that we studied for this piece did just that when they got started.

Casper’s launch party in Los Angeles, featuring a performance by rapper Warren G.

Their competition was well-known. They were not. Their competitors spent millions of dollars on advertising every year. They could not. They needed to change this state of play quite rapidly and get at least some semblance of traction — otherwise, they would not be able to survive.

In some cases, these companies pursued traditional means like physical advertising but with a more contemporary spin. In others, they got attention in purely unconventional ways. In every case, they got their names out early and started building up a reputation with both their early adopters and their potential future customers.

Casper: How Casper broke into the $15B US mattress market by pretending to be a tastemaker

The mattress market in the US alone is worth an estimated $15B. Despite this, few people relish the experience of visiting a mattress store or actually buying a new mattress. At the International Sleep Products Conference in 2015, it was professed by one speaker that “buying a mattress is a treacherous affair, not unlike purchasing a kidney on the black market.”

Casper, in some ways, has broken into that $15B market and taken its own share of it by consciously choosing not to be seen as a typical mattress company.

This strategy goes back to the company’s origins. Casper’s founders set out to build a “digital-first brand around sleep” from the start. It was never just about a mattress.

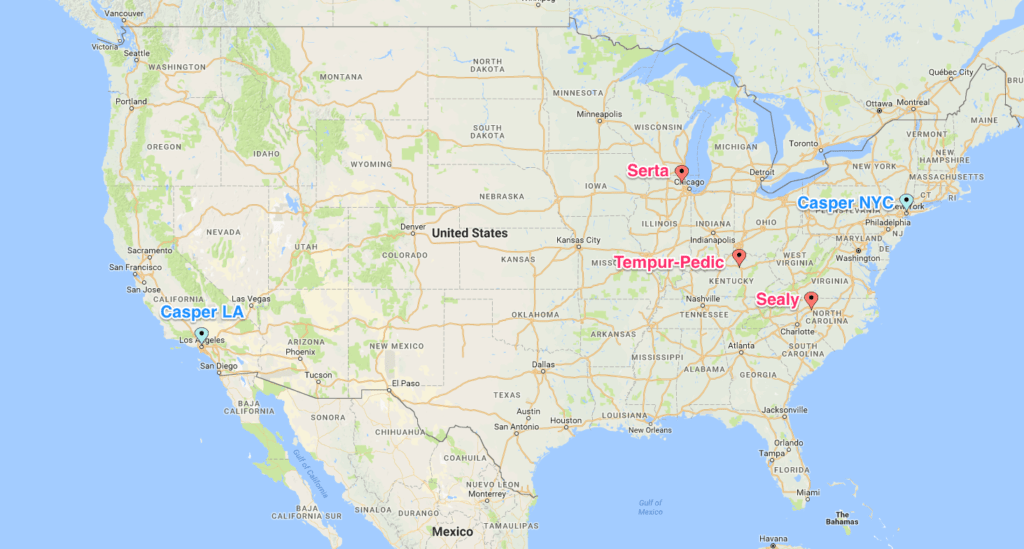

To build that kind of brand quickly, the company decided to short-circuit the process of mindshare-acquisition by going straight for the American tastemaking jugular. It focused its marketing efforts on just 2 cities:

- New York City: The cultural and financial capital of the world

- Los Angeles: The arts capital of the world

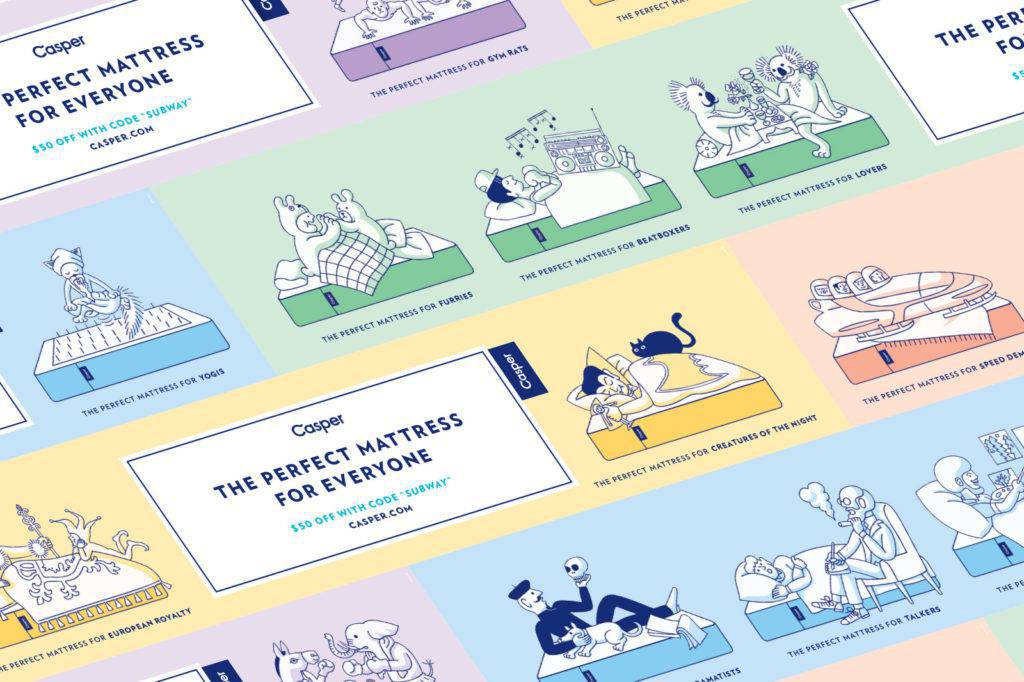

Casper’s headquarters were in NYC. Every time it “dominated” an underground MTA station with its cheerily-designed ads, it was to reinforce the message that its brand was trendy — and urban.  Casper also reached out to various Instagram and Twitter influencers, leveraging its Hollywood connections to get some high-level buzz going around its mattresses. The company opened a satellite office in LA with the main objective of getting more influencers on board.

Casper also reached out to various Instagram and Twitter influencers, leveraging its Hollywood connections to get some high-level buzz going around its mattresses. The company opened a satellite office in LA with the main objective of getting more influencers on board.

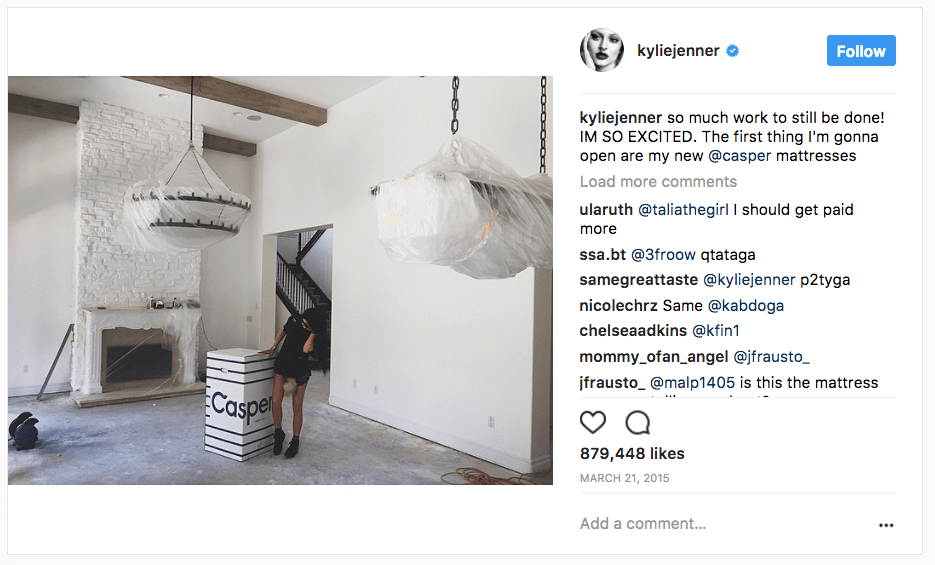

When Kylie Jenner posted a picture of her new Casper mattress in March 2015, it got 800,000+ likes and immediately doubled Casper’s net mattress sales.

Casper pays “influencers” with large follower counts large sums of money to promote its mattresses on Instagram and Twitter.

All over Instagram and Twitter, you can find heavily retweeted and liked images, GIFs, and videos of influencers sitting and smiling with their blue and white-striped Casper deliveries.

This NYC and LA-focused strategy stands in striking contrast to the geographical distribution of your average mattress company.

Serta, Tempur-Pedic, and Sealy, which accounted for about half of the entire mattress market as of 2016 according to Statistic Brain, are headquartered in Hoffman Estates, IL, Lexington, KY, and Trinity, NC respectively.

Much of Casper’s early growth had to do with turning something quotidian into something cool and desirable. The company built a culture around sleep — something that could transcend mere foam and latex.

Much of Casper’s early growth had to do with turning something quotidian into something cool and desirable. The company built a culture around sleep — something that could transcend mere foam and latex.

Casper did that by moving out to the coasts and calling upon the tastemakers and socialites to help the company build its brand. Harry’s, on the other hand, did it purely online. It didn’t use influencers. It tapped into the psychology of the waiting list to drive demand.

Harry’s: Why 100,000 people lined up for a Harry’s razor subscription

When you think of the things people wait in line for, you might think of the new iPhone. You probably don’t think “the new razor.”

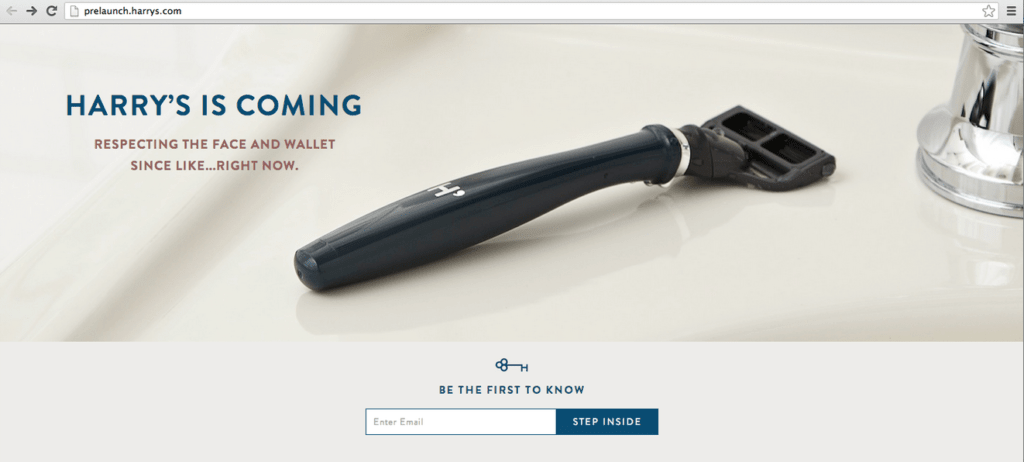

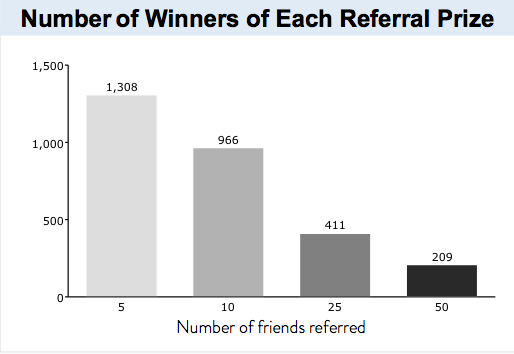

And yet Harry’s was able to get 100,000 potential customers to give the company their email addresses in just 1 week through its pre-launch campaign, according to an interview with the Tim Ferriss blog.

Harry’s was co-founded by Jeff Raider — one of the co-founders of Warby Parker — so he started off with a good understanding of what worked as far as D2C products go. Find something people overpay for relative to the cost to manufacture, then make it cheaper. Raider further elaborates on his strategy saying that:

“We saw a situation in which people were paying lots of money and they didn’t have to — sometimes the cost of making something is quite detached from the cost of purchasing that thing. I think about disruption as being a way to innovate and so blatantly change things for the better that you become an industry standard. That’s what we’re after.”

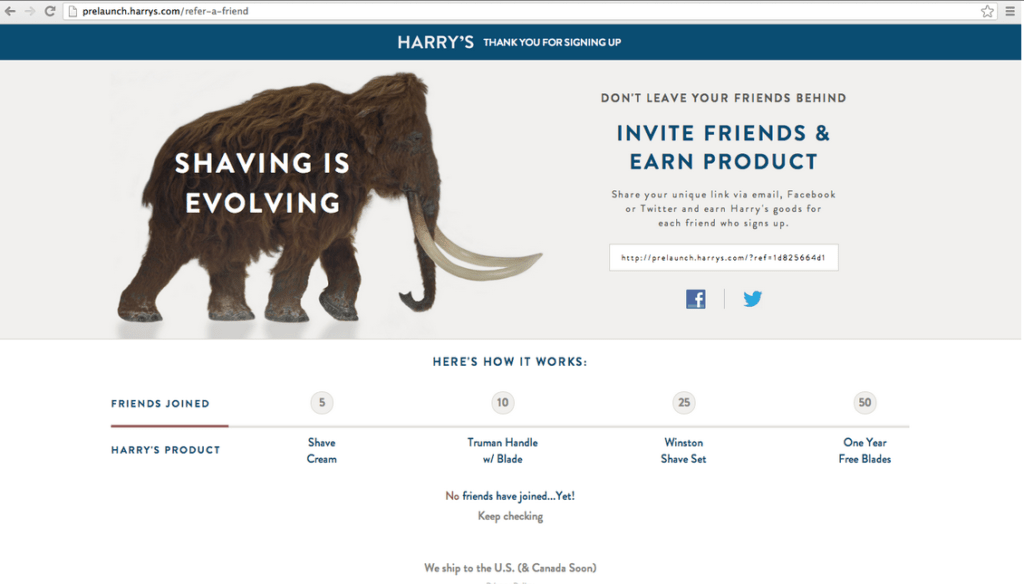

But where Warby Parker was very much a soft launch, Raider decided Harry’s would launch with more of a bang. The basic idea was simple: a waitlist. Users who wanted Harry’s, with its promise of better razors at lower prices, could sign up for the list, but those who shared the campaign with their friends and social networks would get all kinds of prizes for doing so, from free handles to razor blades to pre-shave gel.

The main pre-launch landing page for Harry’s.

The main pre-launch landing page for Harry’s.

100,000 people signed up, which generated a huge list of potential customers for Harry’s. It also gave the company a chance to start doing some customer development work, as sending out free handles and razors to the most prolific referrers allowed the company to get a sense for how people felt about its product before releasing it to a wider audience. Harry’s made various tweaks to its handles and razors based on what it learned from those freebie winners early on.

After signing up, the Harry’s campaign prompted you to share the waiting list with your friends in exchange for various prizes.

The campaign had some simple but effective incentives to encourage people on the waiting list to send links to their friends. The more people you invited, the more prizes you could get:

- 5 friends: free shave cream

- 10 friends: free handle with blade

- 25 friends: Winston shave set

- 50 friends: a year supply of free blades

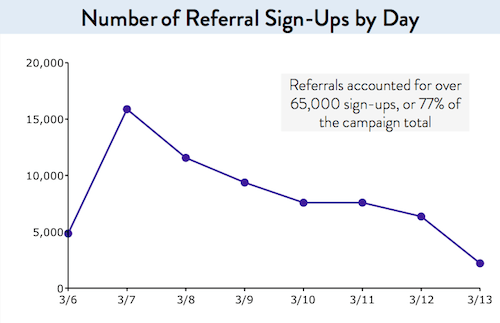

The results showed that the incentives were powerful at encouraging people to share Harry’s with their friends.

More than 1,300 people shared Harry’s with 5 of their friends. Almost 1,000 shared it with 10 of their friends.

Getting that many potential customers’ email addresses is a coup for a startup— not only do you have a list of potential future customers on hand, but you also have some indication that those people really want to give you money.

In a sense, Glossier was able to engineer a similar formula — get engagement first, then launch the product.

get our direct-to-consumer cheat sheet

Learn secrets to success from our analysis of Casper, Glossier, Warby Parker, and 11 other D2C companies.

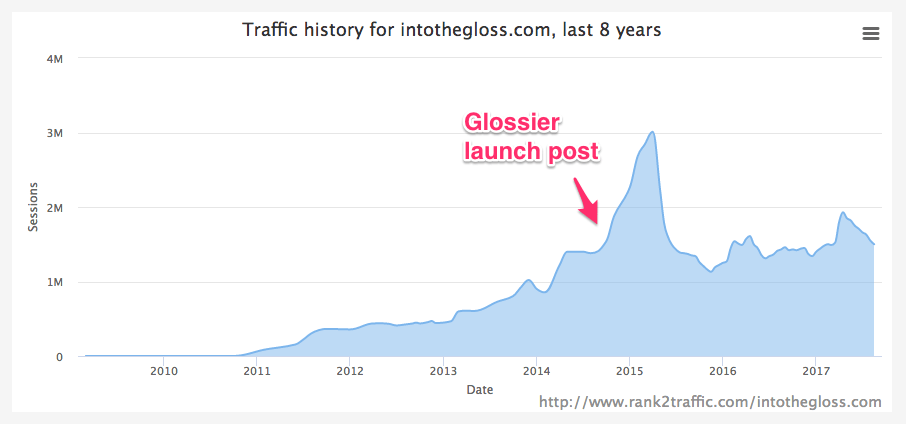

Glossier: How Glossier turned 1.5M blog readers into $35M in funding

Glossier founder Emily Weiss started her blog Into the Gloss in 2010 while still an intern at Vogue. The idea was to talk to celebrities and various moguls about their makeup rituals, trying to write about them in a more casual, authentic way.

The blog got popular, grew, and eventually hit 1.5M unique views every month. It was then that Weiss took the leap into product by launching Glossier — “A total evolution of the same mission, but with tactile content,” as she told Buzzfeed.

From a makeup blog to makeup products; from “Into the Gloss” to Glossier. Weiss’ blog has been invaluable in helping her product line grow its revenue 600% year-on-year.

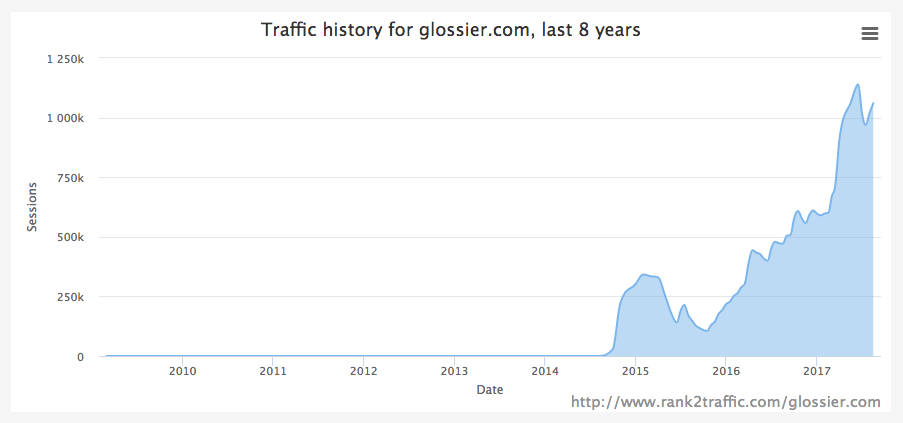

Traffic histories of intothegloss.com and glossier.com illustrate how traffic from the former could be funneled into the latter.

Traffic histories of intothegloss.com and glossier.com illustrate how traffic from the former could be funneled into the latter.

When first launching a product called the Milky Jelly Cleanser, for example, CTO Bryan Mahoney recounts extensive product research going on the Into the Gloss blog. Weiss posted in January 2015 asking her readers, “What’s your dream face wash?” As they got answers, they classified the responses that they got by ingredients and concepts. Over the course of analyzing those 400+ comments, they came to a formulation they believed would be a hit with their audience.

The blog isn’t just a valuable vector of product research — it’s a source of more prepared and enthusiastic consumers in and of itself. Mahoney told Digiday that people who read Into the Gloss are about 40% more likely to buy products from Glossier than other customers.

Glossier’s branding reinforces the idea that beauty and makeup are everyday things. You don’t have to spend hundreds to look good — it’s something that ordinary people can accomplish.

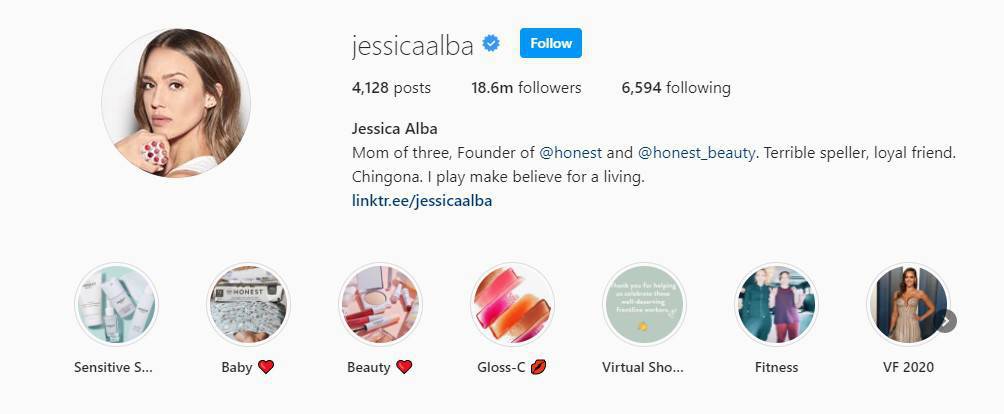

You might not assume that the same message would resonate for a brand like The Honest Company. After all, its founder has about 18.6M followers on Instagram. But The Honest Company founder Jessica Alba was inspired to start her business by a very human concern — one relatable enough to turn The Honest Company into a company once valued at $1.6B.

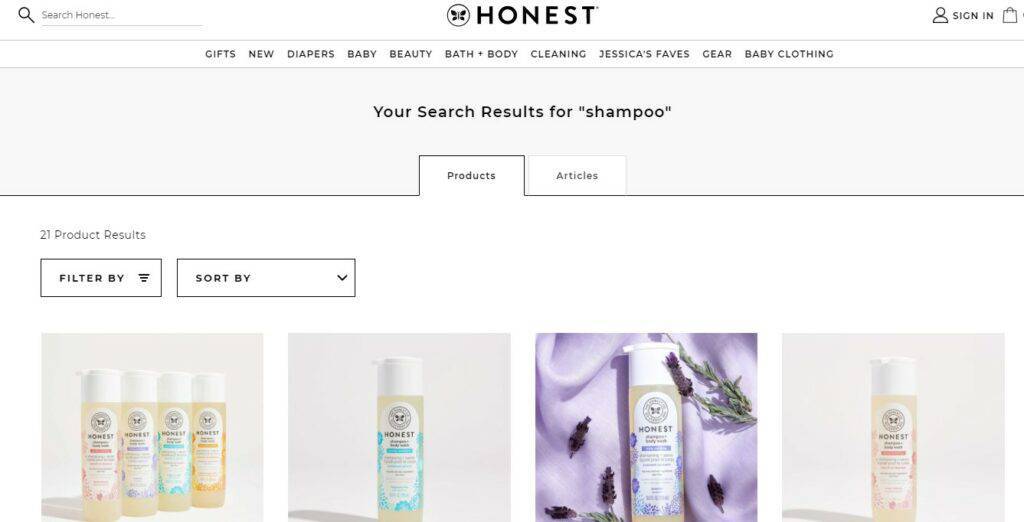

The Honest Company: How it helps to have a founder with 15,000,000 Instagram followers

Celebrity founders can be purely ceremonial — percentage points on a cap table who get paid because of the exposure they bring to the company. That is not the role Jessica Alba played starting up The Honest Company. But she was able to use her celebrity status to textbook perfection in getting the company noticed and evangelizing its story.

Today, The Honest Company is facing an uphill battle to restore its reputation (and valuation) amidst class action lawsuits over its products’ claims and forced recalls.

At one point, however, The Honest Company was a CPG darling. Within a year of launching, it hit $10M in revenue. By 2014, it hit $150M.

One powerful method of getting the word out about your company — having a celebrity founder who’s more than a figurehead (Jessica Alba for The Honest Company).

One powerful method of getting the word out about your company — having a celebrity founder who’s more than a figurehead (Jessica Alba for The Honest Company).

The Honest Company got started while Alba was pregnant with her first child. Aware of how sickly she’d been as a child — how many allergic reactions she’d had to everyday household items — Alba set off furiously Googling all of the ingredients in the soaps and detergents she’d be using to clean the baby and her clothes. The seemingly unending process of trying to find safe and verifiable cleaning products for her unborn child set her off on a quest that led to the founding of The Honest Company.

Part of what sets The Honest Company apart from many of the others that we studied is the relative scale of its product line. Rather than starting with just one or a handful of products, it launched with 17. Many of Alba’s advisers warned against this, but for the specific market they were addressing, it was an important, calculated maneuver.

Any parent who wanted to buy chemical- and irritant-free diapers was also going to want chemical- and irritant-free baby wipes, and chemical- and irritant-free shampoos, and so on. If they couldn’t get most everything from one place, then they weren’t likely to go hunting around different stores — they were likely to go to a brick-and-mortar retailer or Amazon.

Products that are used up and must be replaced relatively quickly are also good products to sell through a subscription model, especially to busy new parents. The subscription model gave The Honest Company a further asset — a built-in incentive to stick with the brand. Gavigan says that:

“You’re cycling in and out of these products, especially with a new baby – diapers, wipes, shampoos, lotions, cleaning products around your home, laundry detergent. You’re powering through these things and you’re doing it unknowingly exposing yourself and your baby to certain things that could and may and have shown to be risky.”

The company wound up doing $10M total in revenue in its first year.

Kirsten Green of Forerunner Ventures holds Alba up as a shining example of the kind of amplification that is possible with a celebrity founder, telling Vanity Fair that “when someone asks if there’s a company that I didn’t invest in that I wish I had, I always say Honest.”

Jessica Alba boasts a huge social media following.

“Alba has redefined the celebrity business model, distancing it from a famous person’s unattainable aspiration and replacing it with a real connection to consumers,” she added. “Celebrities need to do more than just pose with a product.”

When you hear about a celebrity co-founder starting a company, it’s usually something like MSNBC’s Greta van Susteren’s apology app “Sorry,” MC Hammer’s ill-fated search engine (WireDoo), or Ryan Seacrest’s “Typo Keyboard.” They’re not products people are using long after they launch.

Jessica Alba, on the other hand, has both proven her public dedication to the mission of The Honest Company. She has 18.6M Instagram followers at her fingertips, while other founders struggle to get any coverage. That’s the kind of reach that Honest used to hit a $1.6B valuation in just 4 years after being founded.

Celebrity isn’t enough to launch a product, but it can certainly be a powerful megaphone. It can also help create a community — having a central, known figure to rally around can make it easier to reach people and build a conversation. If successful, that community can eventually take off and be self-sufficient, as we can see in the case of food replacement company Rosa Labs and its first product Soylent.

Soylent: Soylent sold $10M+ of meal replacements by making them more like software

Soylent may sell only a few real products — its eponymous meal replacement drink and a nutrition bar — but the company turned an offering that’s fundamentally food into something that looks more like a software platform with continuous updates and an open-source ethos.

That lets Soylent get the benefits of launching (hype, new insights from your customers) on an ongoing basis.

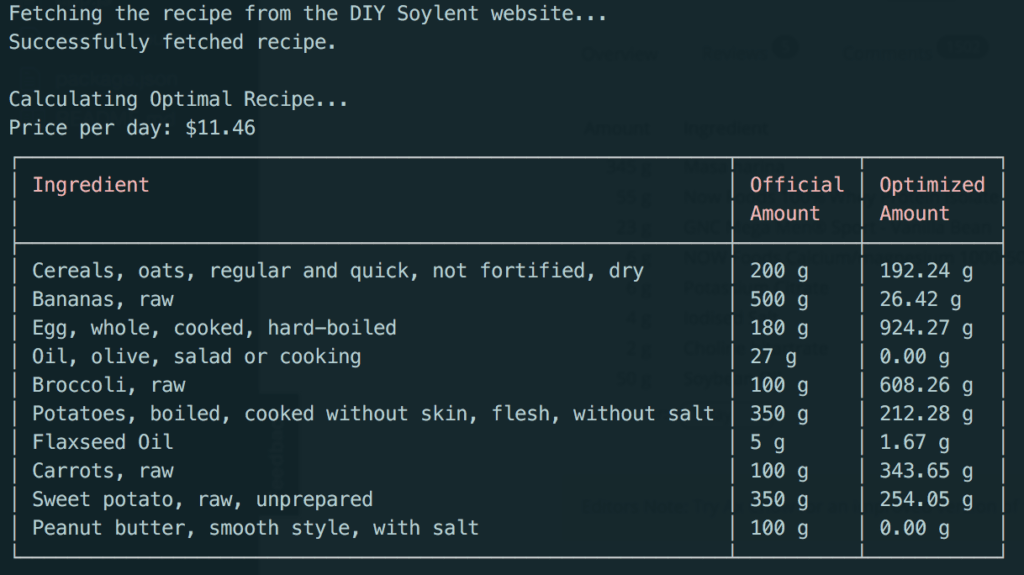

A screenshot of a machine learning-based tool that will help you build your own meal replacement just like Soylent — all you have to do is enter your ingredients. (Source: Laverty)

A screenshot of a machine learning-based tool that will help you build your own meal replacement just like Soylent — all you have to do is enter your ingredients. (Source: Laverty)

Of course, this doesn’t always work out — in 2016, the ill-fated release of the “Soylent Bar” resulted in a vomiting epidemic that ended in the company halting production. A year later, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency banned the startup from operating in Canada due to it not meeting certain nutritional standards required to be classified as a meal replacement. And yet these are the kinds of issues that are easier to surmount when you are constantly reinventing yourself. Soylent Bars need not be an albatross if you can just shed them from your product line.

This squares with the long-term strategy behind Soylent as an ever-evolving product. Co-founder Rob Rhinehart started off his experiments with Soylent by posting recipes he was trying on his personal blog and sharing them with others in the biohacking space. “Soylent” itself has come to refer more to the idea of “food replacement” than any specific company or product in the space, and that’s because of this ethos of continual improvement.

It’s a message that resonated loudly with the backers of Soylent’s original crowdfunding campaign, which got them $755,000 (its original goal had been $100,000), and helped them raise $50M more in May 2017.

Those are software company numbers, which makes sense given the affinity between the business models of Soylent and software.

One of the engines of the tech industry’s rebirth after the dot-com crash was cloud technology and the “as-a-service” revolution. Suddenly, consumers could access software over the web — and developers could push updates continuously. This allowed software to improve gradually over time. Customers no longer had to wait for a new version to be physically pressed to a CD, shipped, and released.

Soylent’s release notes look more like something from a developer blog than a food blog.

Soylent’s release notes look more like something from a developer blog than a food blog.

Soylent takes the same agile methodology and applies it to food. Each new version gets a new decimal-point version number (e.g. 1.2, 1.3, 1.4) and a set of release notes on the blog. Each new version also addresses shortcomings in the previous product and iterates based on testing and customer feedback.

Soylent’s customers are eager and enthusiastic about updates to the formula and changes to the way the powder tastes. Over 36,000 Reddit users are subscribed to the main Soylent subreddit, /r/soylent. Hundreds are reading about and reviewing different Soylent shipments at any given time, asking questions about which versions taste best and what other food items to mix Soylent with.

Each update, however, is merely about bringing small incremental improvements to the core idea behind Soylent. As with Casper and Harry’s, Soylent is meant to be “the one product” that a consumer needs in this space. In other words, Soylent is designed to be more or less nutritionally complete. And the bond it has with customers ensured that the business kept growing even during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Like many on this list, BarkBox is an example of a company seeking to deliver a better customer experience by offering fewer choices. By compressing the treat-toy-accessory buying experience into one package, BarkBox simplified modern pet accessory shopping. But to make people take notice, BarkBox looked to the familiar channel of social media for some viral leverage.

BarkBox: How BarkBox hit 600,000 customers with little marketing spend

BarkBox started in 2011 as a side project for co-founder Matt Meeker. He joined forces with fellow tech entrepreneurs Henrik Werdelin and Carly Strife, but kept the startup lean, only hiring one staff member a year into the launch and building a basic site to test interest.

As they grew, Meeker and company began noticing videos on Facebook showing BarkBox customers opening the boxes with their dogs, giving BarkBox an insight that would fuel their growth to 600,000 customers and beyond.

These early adopters of BarkBox wanted to show off that they were in on a new service. The founders grasped the marketing opportunity and decided to build a strategy around it.

Today, there are thousands of BarkBox opening videos on YouTube.

The reason customers enjoyed opening BarkBox with their dog was clear — people love showing off their dogs on social media, and a box full of treats provides an ideal opportunity for content.

BarkBox leaned into this customer trait, designing every part of the BarkBox experience in a way that would make subscribers feel like they were part of something special — and make them want to share.

From monthly themes which provided month-to-month variety to their content creators, to hand chosen items the team found by combing sites like Etsy, to the upscaling of the packaging itself and the inclusion of huge BarkBox logos, BarkBox turned viral-box-opening into a science.

The company devised numerous ways to encourage recipients to post unboxing videos and photos on social media. This included a referral program and coupon codes. When a new BarkBox customer took a video of their unboxing and uploaded it to YouTube or Facebook, tagging it with a specific hashtag, they could get a discount on their next order. Additionally, a content creator who featured a promotional code in their video, or other content, could get a cut of the proceeds from BarkBox.

This proliferation of social media sharing defined BarkBox’s marketing approach and put the startup on a growth trajectory that continues to this day.

BarkBox is a social media leader in the online dog space, with nearly 3M fans on Facebook and more than 1.7M on Instagram.

“If you took out social media, Bark and Co. wouldn’t be a company,” says Stacie Grissom, head of content at BarkBox. “We’ve really invested in entertaining people and engaging with people in deep ways by talking about their dogs and showing them other people’s dogs.”

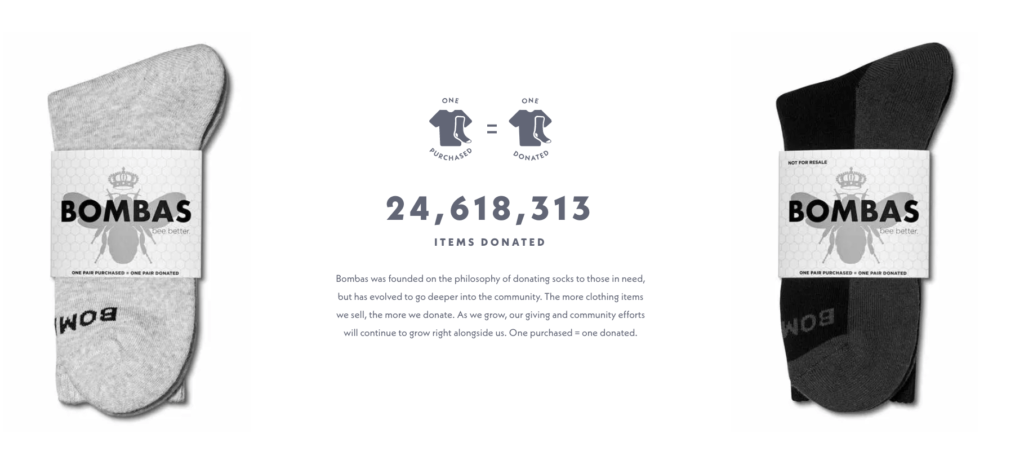

Bombas is another company that aims to be inextricably connected with its community. Bombas is a buy-one-give-one company: for every pair of socks you buy, a pair gets donated. But in an attempt to strengthen its brand proposition to customers, Bombas decided to keep its philanthropic mission local: supporting the homeless in and around the places where Bombas sells its wares.

Bombas: How a sock company pitched its business as a mission

Socks are among the most requested clothing item at homeless shelters. However, most homeless shelters, citing hygiene concerns, do not allow second-hand socks to be donated.

This helps explain why Bombas’ adoption of the buy-one-give-one business model that many other companies have used, including Warby Parker and Toms, wasn’t merely derivative — it was targeted at providing a specific type of support for a marginalized group that was unlikely to get it otherwise.

This may also be why Bombas’ campaign has been generally well-received by a public increasingly suspicious of “guilt laundering” from companies supposedly doing good for the world.

One common criticism of the buy-one-give-one model argues that companies like Tom’s that distribute wares in impoverished areas can effectively out compete local providers, distorting the market and dampening economic development.

Instead of focusing its efforts abroad, Bombas focuses its donations on homeless shelters in the United States — an advanced market where the risk of knock-on negative economic effects would be limited.

The idea was also part of the genesis of the company itself. Co-founders Randy Goldberg and David Heath, colleagues at a lifestyle website, were reportedly inspired to start a sock company when they read that socks were the most requested item at homeless shelters.

Bombas donates a pair of socks for every pair sold.

This kind of mission-based marketing relies on customers believing that they’re doing good when buying from a company, a perception that Bombas has sought to cultivate.

Toms was a big early success in this field, but critics took shots at the Toms model for everything from being a “terrible way to help poor people” to fostering a sense of “aid dependency” in recipients of the company’s philanthropic efforts.

Bombas aimed to avoid these kinds of criticisms by focusing its philanthropic efforts in 2 ways — by staying close to home, and by giving away a product that targets a specific unfulfilled need of its recipients.

get our direct-to-consumer cheat sheet

Learn secrets to success from our analysis of Casper, Glossier, Warby Parker, and 11 other D2C companies.

The company stayed true to its mission during the Covid-19 pandemic, having donated more than 40M pairs of socks to date as of October. The business was booming as well, and Bombas kept growing its customer base.

Gymshark has also portrayed itself as being on a mission, although not a philanthropic one. The British activewear producer took it upon itself to provide gym enthusiasts with apparel that’s both practical and ‘Instagrammable.’

Gymshark: Using influencer marketing to grow a cult-like following among gym-goers

Ben Francis founded Gymshark in 2012 in the UK when he was just 19. Unhappy with existing sportswear choices, he wanted to build a clothing brand that offered affordable and fashionable products to gym-goers. But competing in this field meant taking on giants such as Nike and Adidas.

Gymshark offers a range of sportswear products. Source: Gymshark

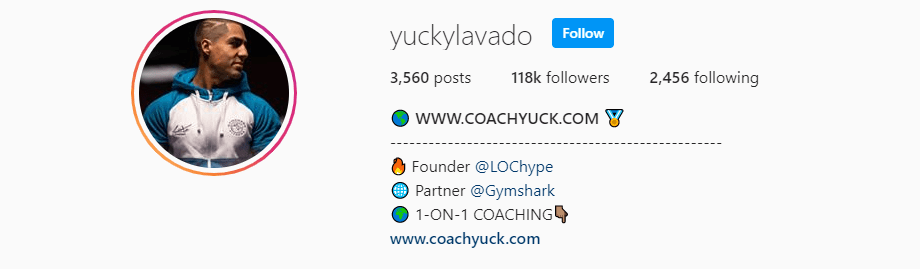

To launch its products and achieve a breakthrough, Francis turned to popular social media accounts in fitness and health niches, making Gymshark one of the pioneers of influencer marketing. Francis says that “At the time, no one else was doing [influencer marketing]. It came totally naturally to us because we were just fans of the guys.”

The company initially contacted high-profile accounts such as bodybuilders Lex Griffin, Chris Lavado, and Nikki Blackketter. In exchange for free Gymshark apparel, these influencers were supposed to wear and promote the products on their Instagram and YouTube channels, driving purchases through affiliate links.

Chris Lavado’s account on Instagram

The strategy proved to be highly successful. Sales boomed, and Gymshark now sponsors 18 influencers, including Irish professional boxer Katie Taylor and the ultra-marathon sea swimmer Ross Edgley. The company has also worked with a number of TikTok influencers, including Wilking Sisters, Rybka Twins, Laurie Elle, and others.

Influencers had duties that extended beyond social media. Called “Gymshark athletes,” they attend offline events and meetups around the world, spending time with their fans and promoting the brand. They ramped up promotional efforts before a new product launch and during major sales, such as a Birthday Sale in June and a Black Friday Sale.

Fans attending Gymshark events. Source: Gymshark

Gymshark uses influencers to bond with gym enthusiasts. And it further deepens brand loyalty by creating an aura of exclusivity around its products. One of the tactics used to achieve this is selling products exclusively through its website and not working with third-party online retailers. And although the company may have missed revenue in doing so, Francis remains committed to this strategy. He firmly believes that “Gymshark has the potential to be to the UK what Nike is to the US and Adidas is to Germany.”

In 2020, US fund manager General Atlantic invested over $250M into Gymshark, valuing the company at $1.3B. The funds will be used to expand the business into new markets, including North America and Asia. And despite the Covid-19 pandemic, Gymshark reported strong growth in sales in this period.

Lesson #3: Building an end-to-end brand starts with a great customer experience

A key focus for these D2C companies is quality. We’ve talked about how they market themselves and how slim, tailored product lines create a kind of prestige around their offerings. But more important to the idea of “quality” here is the overall experience of buying the product, rather than the product itself.

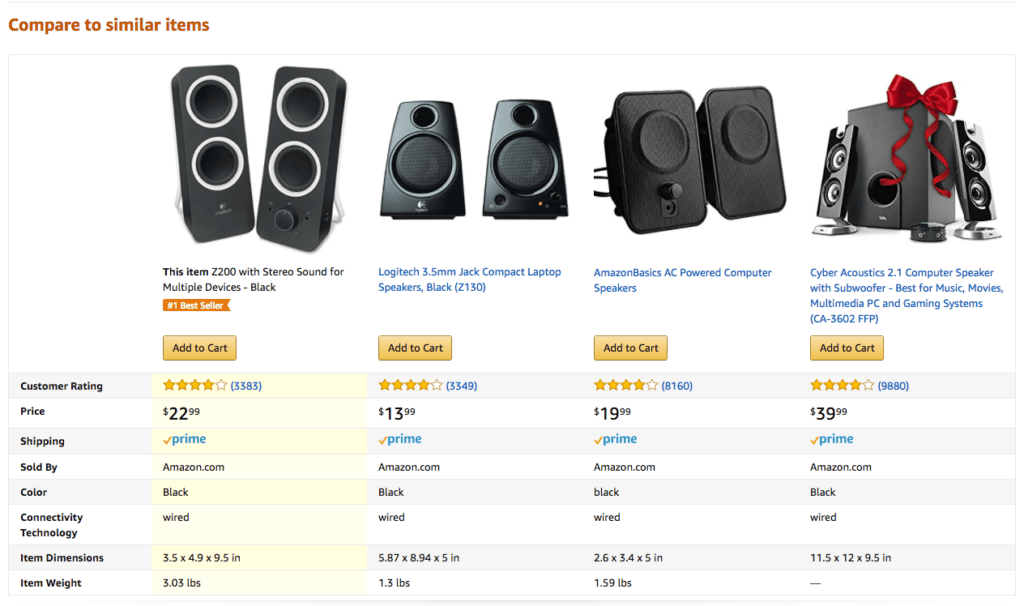

In that regard, D2C brands have positioned themselves as the antithesis to traditional retail giants. Take, for example, a typical buyer journey on Amazon. You go looking for a pair of speakers and are immediately offered a huge selection of choices designed to get you to the checkout as quickly as possible. If you’re unsure about the options, the “Compare to similar items” section might offer even more products.

On Amazon, quality is delivered through a tailored selection of choices — each one right for a different kind of shopper.

Depending on whether you just need a basic set of speakers for a party or are looking to invest in a decent pair for your home office, you should be able to get what you want no matter what product you click on initially. But you’ll have to make choices and accept tradeoffs. A cheaper product may not be as good as a more expensive one. Amazon’s model gives you the tools to choose but it’s you who has to navigate an array of choices and make painful compromises.

The successful D2C companies we looked at, for the most part, approach quality from an entirely different direction. Rather than catering to different levels of interest and motivation — here’s a cheaper bed with [X, Y] features and a more expensive one with [X, Y, Z] features — they cater to the desire for simplicity. They cater to the desire to avoid choosing and the desire for something that is just fine.

You can see this if you read critical reviews for many of these products on the internet. A fair number of mattress critics say Casper beds are overhyped. The Honest Company has been in plenty of hot water over the quality of its products. And commenters have described Glossier as ripping off other products and putting them in cute packaging.

What they do rave about is the process of actually getting a Casper mattress delivered. What they love is how easy it is to always have fresh blades on hand with Dollar Shave Club, and how simple it is to buy The Honest Company soap. And they have to hand it to Glossier’s choice of packaging. This trend was summed up by Sam Lessin, a tech entrepreneur, who said that “The thing to understand is that Good Enough products aren’t purely commodities racing to the bottom. They are a class of products where the end-to-end experience of selection, purchasing, and customer service is more important than the product itself.”

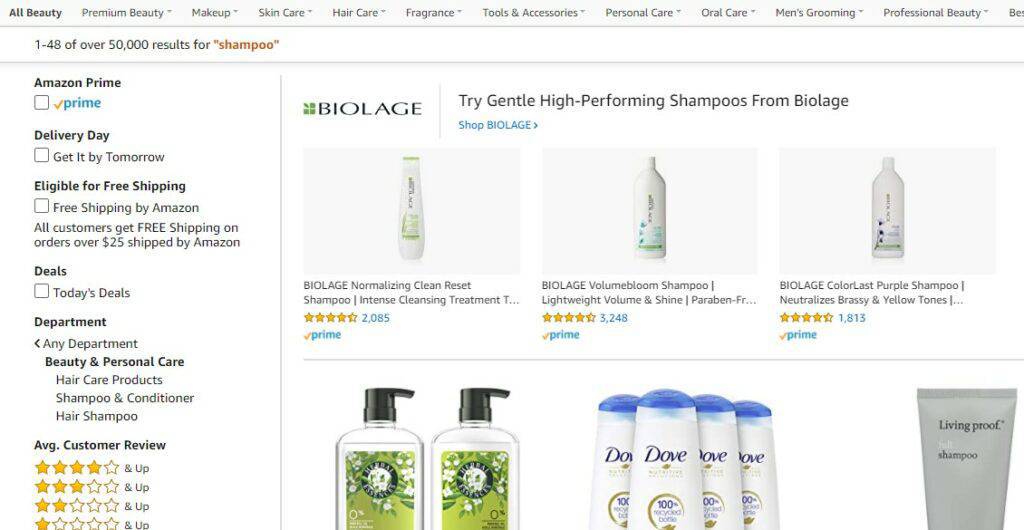

And providing more choice can sometimes be a burden for the consumer. If you’re an expectant mother looking to stock up on shampoo for when your new baby arrives and you search the word “shampoo” on Amazon, you get over 50,000 results. If you’re especially ingredient-conscious, then you may have to comb through pages of results to find something sufficiently chemical-free that you actually feel comfortable using.

On the other hand, there are only 21 search results when you search for shampoo on The Honest Company’s site. This greatly simplifies the process of buying something baby-appropriate, and so it’s actually faster and easier than going through Amazon.

These companies aren’t necessarily raising the bar on quality or selection (though that may be part of their appeal). They’re raising the bar on the customer experience. They’re delivering a far better razor buying process and a better mattress buying experience. They’re delivering the soap you need in a fraction of the time it would take to find it on Amazon. Their products may be just Good Enough in most cases. The end-to-end user experience, however, is so much better that it elevates them above their traditional competitors.

That’s central to their D2C nature. Because these brands can truly own the customer experience and delivery, they can create an end-to-end customer experience that is better than anything Amazon or a traditional retailer can offer.

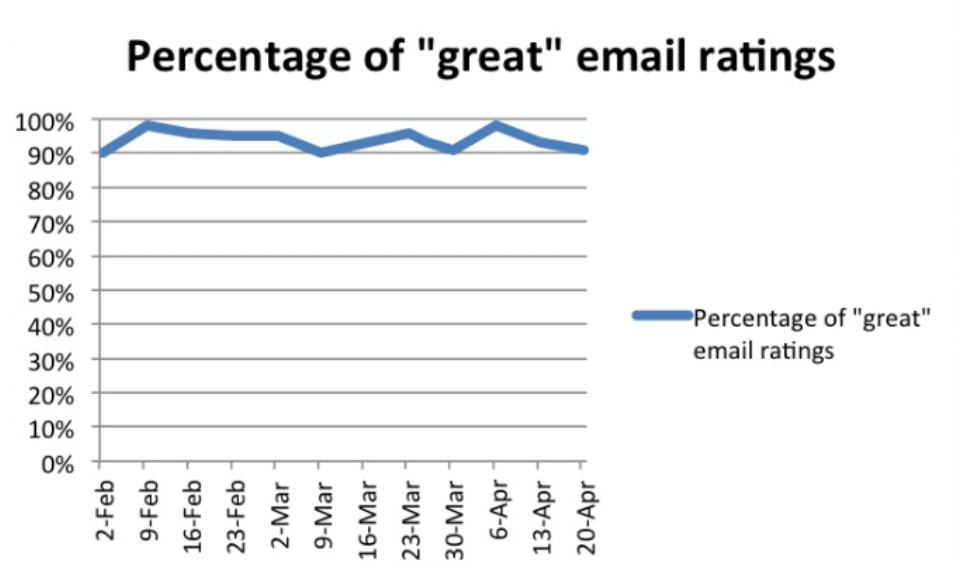

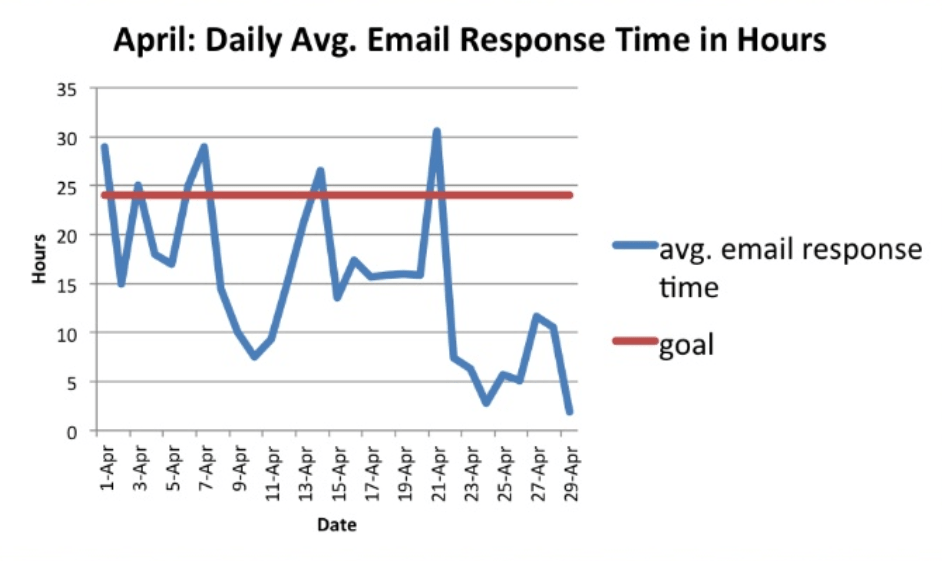

Bonobos: Why an apparel brand aims for 90%+ “Great” ratings on its support emails

As a previously unknown brand, Bonobos saw early on that providing a differentiated customer experience was going to be important.

It needed men to feel confident ordering relatively pricey pants online, and it needed those men to recommend those pants to their friends. This was 2007, so buying clothes online wasn’t new — but there was still friction there. There was one shining model in the e-commerce space to imitate, and that was Zappos.

Bonobos founder Andy Dunn saw the exponential growth of Zappos and realized that its growth had little to do with the products they sold (which you could get anywhere) and everything to do with this dedication to “insanely great” service. He saw that “the best way to convince people to regularly buy clothes from a new online company,” as Business Insider wrote, “was to primarily focus on a level of customer service other businesses didn’t offer.”

For Bonobos, that meant cultivating a culture of ultra-responsivity on its support team in the first years — a culture that resulted in prompt replies across various customer service channels, including phone, email, and social media:

- 90%+ rate of responding to all phone calls within 30 minutes

- 90%+ rate of “great” email ratings

- Sub-24 hour average email response time

Central to the Bonobos idea was great pants. But the brand needed to embody this idea of overwhelmingly-great service too. The company didn’t just make great pants, it made shopping for them easy.

That branding created an early impact. A good metric for measuring the success of branding is direct traffic rate — how many people come to your site simply by typing it into their browser vs. through referral or other means.

In October 2020, Bonobos had a direct traffic rate of 48.97%, according to SimilarWeb.

The level of the Bonobos customer experience has remained high over time. In both 2015 and 2016, Bonobos won Multichannel Merchant’s Customer Experience Leader award, beating out companies like Fossil, Lowe’s and Coach.

The company also appeared to be relatively unscathed by the Covid-19 pandemic. It closed stores in March and reopened them 3 months later without announcing any layoffs. The company didn’t reveal to what extent the pandemic affected its revenue results, but many D2C men’s brands thrived amidst the lockdowns and shelter-in-place orders.

Among the companies that have taken the Bonobos ideology to the next level, Soylent stands out. The Soylent team is actively involved in the community, almost treating its customer base as an extension of the company. That communal ideology has not only helped it attract high-profile funding but powered its hypergrowth.

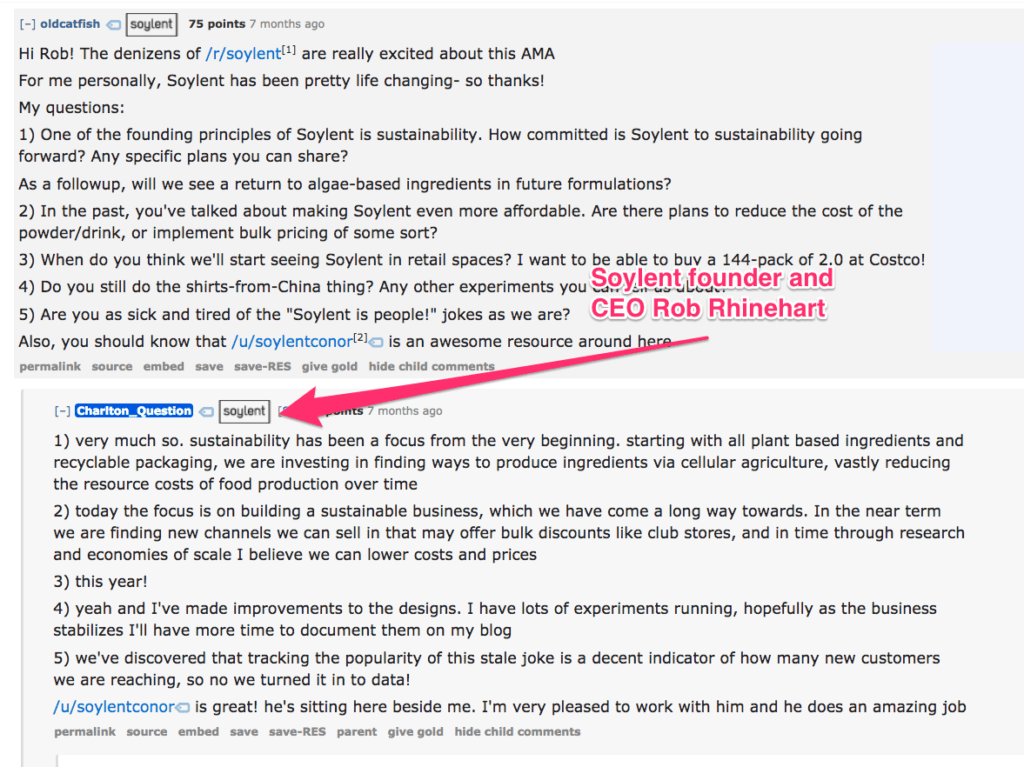

Soylent: The subreddit that convinced a16z to invest in Soylent

With some products, investors are just as interested, if not more interested, in the community than they are in the core product’s features and capabilities. A group of engaged and sincere customers is something far more rare, and potentially more powerful, than a good product alone.

With meal replacement startup Soylent, the Reddit community that emerged in the wake of the product’s launch was strong enough that it convinced Andreessen Horowitz to lead a $20M round in the company in 2015. Chris Dixon, who works at the famed VC firm, wrote a blog post announcing the close of the investment, stating that:

“Soylent is a community of people who are enthusiastic about using science to improve food and nutrition. The company makes money selling one version of that improved food (some users buy ‘official Soylent,’ others buy ingredients to make their own DIY Soylent recipe). If you look at Soylent as just a food company, you misjudge the core of the company, the same way you would if you looked at GoPro as just a camera company.”

The key point here is that Soylent was never just a product — it started life as an experiment into “biohacking” that CEO and founder Rob Rhinehart posted about on his personal blog.

In the post, “How I Stopped Eating Food,” the then-software-developer Rhinehart talked about the nutritional meal replacement he had developed to save himself time during the day. He wrote up the complete list of ingredients and the exact steps he took to develop it so people could tweak it themselves. The Soylent subreddit was born a month later.

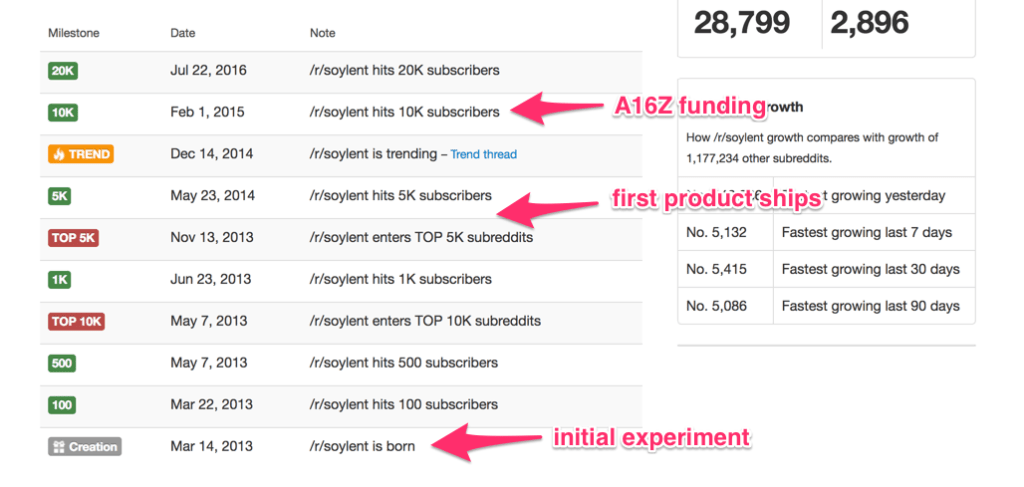

The growth of the Soylent subreddit over time, pegged to important milestones in the history of the Soylent corporation.

The growth of the Soylent subreddit over time, pegged to important milestones in the history of the Soylent corporation.

The early subreddit was a place for these experimenters to discuss ingredients, dosages, warnings, and help everyone craft a better “anti-food” nutritional supplement.

A safety warning posted by one /r/soylent user early in 2013.

A safety warning posted by one /r/soylent user early in 2013.

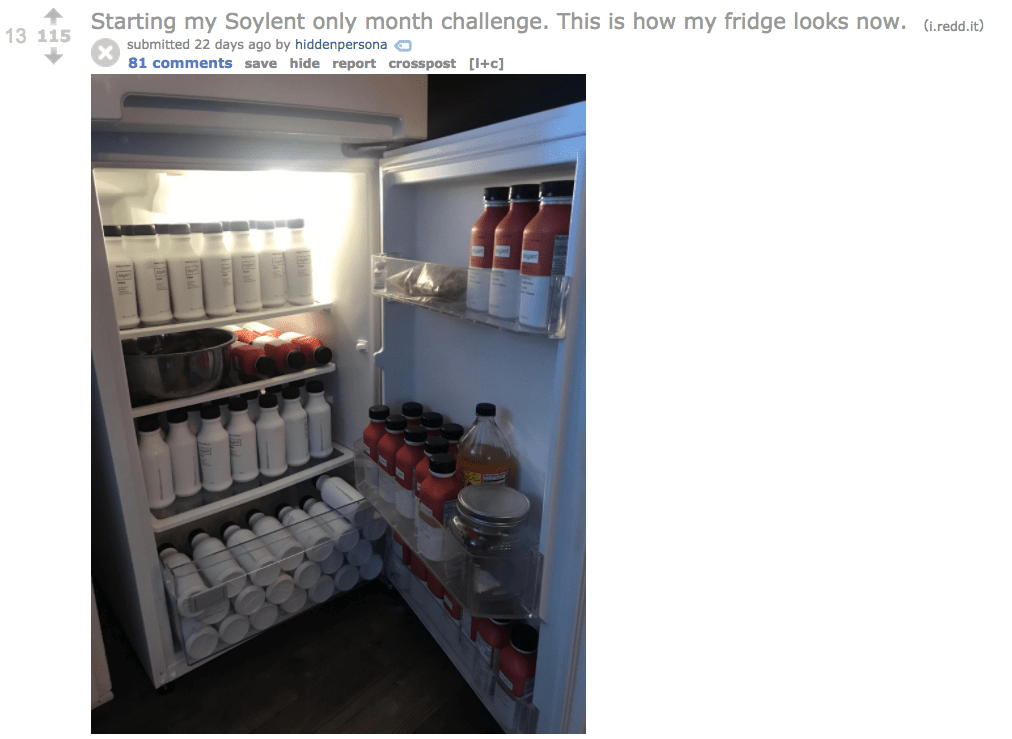

By 2018, the official Soylent subreddit at /r/soylent had almost 29,000 subscribers. Contributors share different Soylent-featured recipes, ask each other questions, and share pictures of shelves and refrigerators bulging with Soylent:

a16z bet that this community around Soylent was potentially a much bigger opportunity than the product alone. That’s because never before had there been such effective mobilization of people around the idea of bringing science to bear on food and nutrition.

a16z bet that this community around Soylent was potentially a much bigger opportunity than the product alone. That’s because never before had there been such effective mobilization of people around the idea of bringing science to bear on food and nutrition.

A few crucial early decisions laid the groundwork for this community taking shape:

- Open sourcing the product: By listing all of the ingredients inside Soylent, and encouraging people to experiment with making their own “versions” of the product, Soylent created a product its customers could help define from Day 1.

- Active participation in the Reddit community: Soylent’s founders and team post regularly on the subreddit, doing AMAs (Ask Me Anythings) and answering customer questions about the company.

Rob Rhinehart posts on the Soylent subreddit as a means of connecting with the community and providing support.

Part of the power of Soylent is that it’s both a product and an idea. You can buy Soylent from the Soylent website, or you can just print out the recipe, buy the ingredients, and make your own. Add in communities like the one on Reddit, and the product can almost distribute itself.

That is not to say the company is operating without challenges. It has reportedly reduced its office size in November 2019 and closed Soylent Innovation Lab. Multiple layoffs were reported as well. And unlike competitors such as Huel, Soylent is yet to report the most recent revenue figures.